Human net fertility1 is complicated. Some things that matter on the margin: winning elections, baby simulators in health class, war, housing costs, religion (both type and intensity), women’s education, population density, racial diversity, STD-induced infertility, baby bonuses, antinatal propaganda campaigns and sterilizations, and status-messaging in soap operas. The full list is much longer. But most of these factors are just not that important—a few percent here, a few percent there, and with sharply diminishing returns.

And cross-cultural explanations are generally not that useful; abuse of them is how you get bad ideas like the development or women’s liberation U-curve for fertility. Trying to explain the ups and downs of fertility across all of humanity with one model is a mistake; there are huge cross-cultural differences and something that might matter a lot in one context (say, acceptance of infanticide for Christians vs Pagans in Rome) might be irrelevant in another (say, fertility collapse in 20th century East Asia). Longitudinal analysis, which look at the same societies over time, is much better.

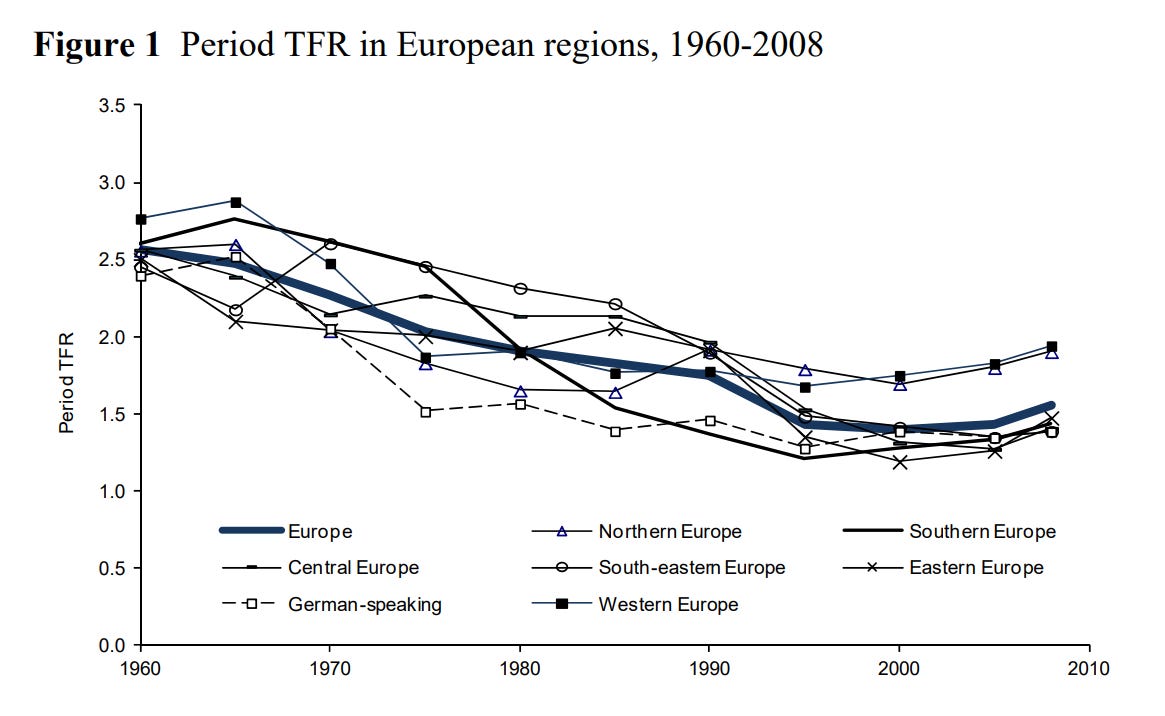

Rather than look at the whole world, which is too diverse for coherent lessons, or a single country, which will be semi-randomly affected by particular legal regimes or events, it makes sense to look at a civilization. And what better civilization than the West, which is both extremely important and better documented than any other? Especially when Western norms are so influential on the rest of the world; if, as Lyman Stone claims, other countries imitating Western low fertility norms is the primary cause of global fertility collapse, figuring out where Western low fertility norms came from to begin with is important! Fortunately, the history of modern Western2 fertility is fairly coherent. There are local ups and downs and country-specific factors, but the demographic history of the West as a whole can be split into five clear stages.

The Five Stages

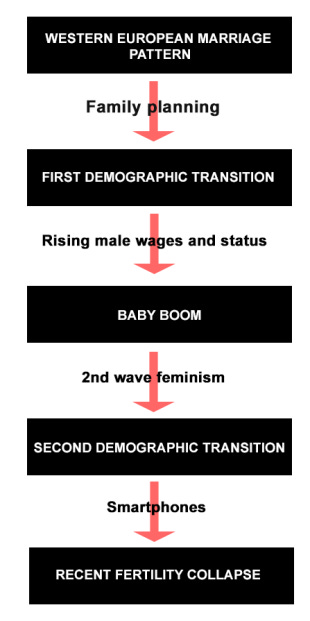

Stage 1: The Western European Marriage Pattern

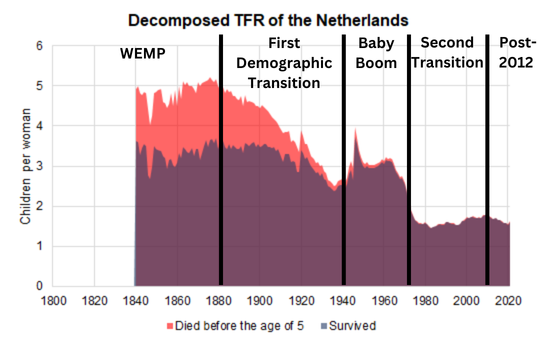

Characteristics: Replacement level net fertility in Malthusian Europe. Far above replacement fertility in the Americas and post-Industrial Revolution.

Proximate cause: Catholic Church-endorsed marriage pattern combined with the post-Black Death importance of geographically-free wage labor.

Further reading: The Western European Marriage Pattern: Definition, Significance, and Misconceptions

While not the only components3 of the Western European Marriage Pattern, the relevant ones to this question are as follows:

Absolute monogamy, with high standards of premarital chastity and fidelity, including very little divorce4. Fertility was almost synonymous with marital fertility, with single-digit percentages of births outside of wedlock5 (and, in an environment with child mortality approaching 50%, illegitimate children without paternal investment did not have good odds of survival) and cuckoldry rates in the range of 1-2%.

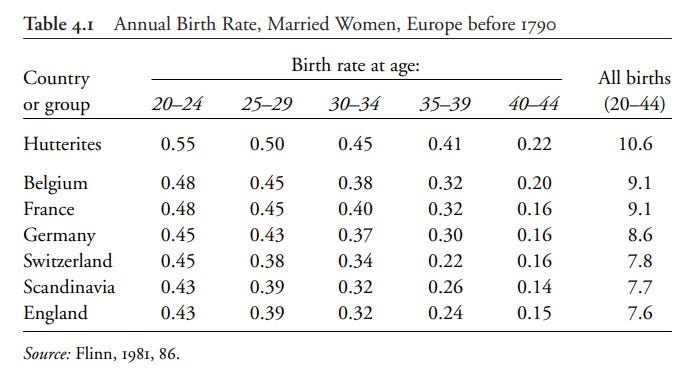

Almost no family planning within marriage. Marital TFRs6 in early modern Western Europe approach the human biological maximum. Family sizes were controlled by delaying marriage or by not marrying at all, not by abortion, infanticide, contraception, or other techniques to reduce fertility within marriage. This is not the preindustrial norm (marital TFRs in contemporary China and Japan were around 57); it is a consequence of the Catholic Church condemning family planning as a sin and the major Protestant denominations (initially) retaining that view.

Neolocality. Couples were expected to wait until they were economically self-sufficient enough to form an independent household before marrying, rather than relying on their parents (this went both ways—parents were much less reliant on their children in old age than in most premodern societies). This meant that marriage was earlier and more frequent when economic conditions were good (the extreme case being the early American colonies, hence their extraordinary growth), and later and less frequent when conditions were bad (the extreme case being after the Irish Potato Famine). In the Malthusian world before the Industrial Revolution, this served as a natural check on population growth and to smooth out the famine-induced boom-bust population cycles typical of agrarian societies. It was this late and infrequent marriage in bad times (and times were usually bad in the preindustrial world) that led to demographer John Hajnal discovering and describing this marriage pattern, but late and infrequent marriage is a second-order consequence of neolocality, not a foundational part of the Western European Marriage Pattern.

The most relevant component here is neolocality. This meant not only near-zero long-run population growth in the Malthusian era, but also comparatively few massive famines or other depopulation events (very useful for social stability and the preservation of capital and records). And when the Americas and Industrial Revolution came calling, rising incomes led to skyrocketing nuptiality led to a massive population boom and temporary European demographic supremacy.

Some readers may be surprised by this, because the Industrial Revolution is often blamed for falling fertility. Actually, the Industrial Revolution, by raising living standards and especially male wages, reduced the average age of marriage and thereby increased fertility. The demographic explosion this caused is what made the “First Industrial Revolution” so revolutionary, leading to centuries of Anglosphere cultural and geopolitical dominance.

First Demographic Transition

Characteristics: Rapidly falling fertility from far above replacement to below, driven by falling marital fertility.

Proximate cause: Moral normalization of family planning.

Further reading: Mind Viruses: In Defense of an Analogy

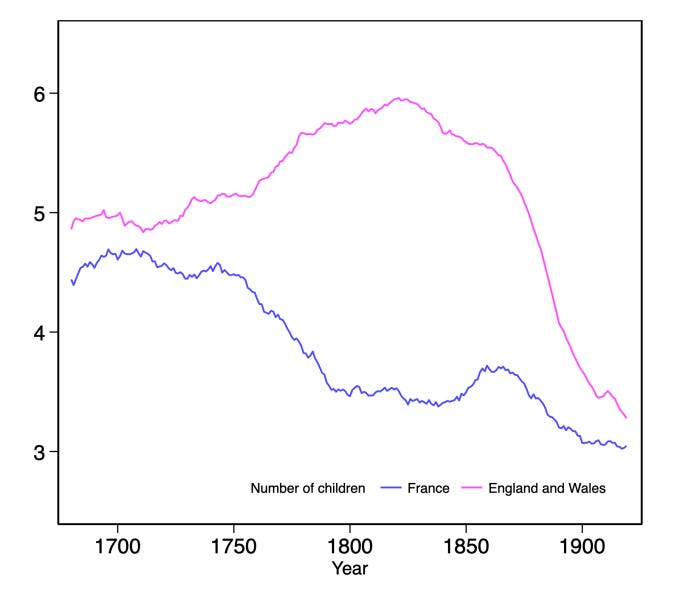

The first demographic transition began in France around 1760 and was greatly accelerated by the French Revolution, before spreading culturally to the rest of Francophone Europe8. In the Anglosphere, it began about a century later with the Bradlaugh-Besant trial (1877)9. The Nordic transition happened around the same time as that of the Anglosphere, and the German one around 1900. Even more than the first-order effects of the Industrial Revolution itself, the timing of the first demographic transition determined the relative strengths of the great Western European powers of the 19th century.

The proximate cause was the addition of family planning to the Western European marriage pattern. This greatly reduced marital fertility, such that even though nuptiality10 didn’t drop much and childlessness actually decreased, total fertility plummeted. In France, the moral normalization of family planning came from secularization and ignoring the Catholic Church. In Protestant Europe, the normalization of family planning was closely linked to Malthusianism and Darwinism, with state churches falling in line with broader cultural currents.

To some extent, this was inevitable; zero family planning with early marriage and collapsing infant mortality leads to massive family sizes11 that most people who are not part of extremely natalist religious groups (think Israeli Haredim; even the Amish or Laestadians don’t go this far) are not willing to deal with. But the timing was highly contingent; the French fertility transition began a century before the mortality transition, the two were more or less contemporaneous in the Anglosphere, and the fertility transition lagged the mortality transition in the Germanosphere, with historic consequences. A difference of a generation or three matters.

Western fertility reached a local nadir around 1930, with most countries solidly below replacement12. At the time, demographers believed this was permanent and writers such as Oswald Spengler prophesied inevitable population aging and Western decline before the rising tide of color. They were wrong.

The Baby Boom

Characteristics: Rapid rise in fertility to well above replacement, driven by increasing nuptiality.

Proximate cause: Rise in young men’s relative wages and status beginning in the 1930s, leading to earlier and more frequent marriage.

Further reading: The Baby Boom: Lessons and Patterns or How to Solve Demographic Collapse

The Baby Boom was primarily a marriage boom, caused by a sharp rise in young men’s wages and social status13, both in absolute terms and relative to their female counterparts. Western fertility went from well below replacement to well above it, though the exact magnitude of the Boom varied by country14.

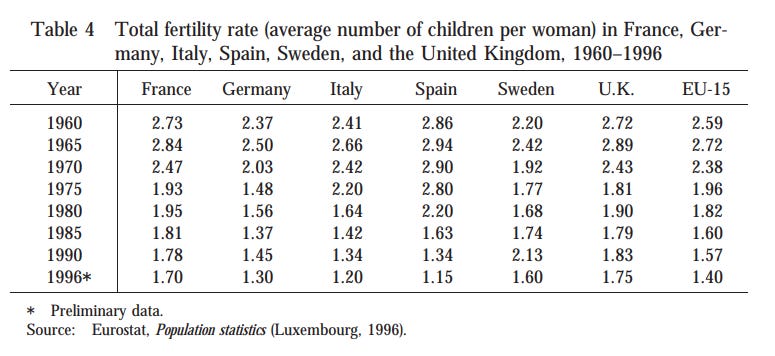

The Baby Boom is so important because it occurred during a time of extremely rapid technological advancement, urbanization, rising incomes and education (for both men and women, though faster for men), and falling mortality. Every Western country near or below replacement in the 1930s was clearly above it by 1960.

With illegitimacy still in the single digits, the boom can be reduced to two things. More marriage (nuptiality) and higher marital fertility. In every Boom country except for France, the United States, and Austria, higher nuptiality explains 85% or more of the Baby Boom.

What caused this dramatic rise in marriage? It turns out it can be entirely explained by a sharp rise in young men’s relative wages and status compared to the young women they sought to marry.

Much as with the First Demographic Transition, contemporary demographers thought this state of affairs might continue indefinitely.

Second Demographic Transition

Characteristics: Rapid collapse from significantly above replacement to well below replacement fertility. Shift from marital to nonmarital fertility.

Proximate cause: Second- feminism and the Sexual Revolution making marriage less useful (leading to lower marital fertility) and therefore less appealing (leading to lower nuptiality).

Further reading: Human Reproduction as Prisoner’s Dilemma

Unlike the first demographic transition, which began decades apart in different Western cultures15 and took generations to unfold, the second demographic transition was extremely coordinated across countries. Within a span of six years, the United States (1973), France (1975), Germany (1970), Britain (1973), and the Nordics (1969) all went from poised for a never-ending population explosion of the sort that gave Paul Ehrlich nightmares to our current path of population aging and demographic decline. This is downstream of the homogenization of the West (culturally, politically, economically, legally), which itself is downstream of better communications technology and post-WW2 American hegemony.

The proximate cause is the enormous suite of changes that fall under the rubric of second-wave feminism and the Sexual Revolution. Some of the most important include:

Unilateral and no-fault divorce. Not only does this reduce marriage rates and increase divorce rates (lowering nuptiality), but the lack of security also encourages spouses to invest more in themselves (via education or career) and less in specialization of labor or “relationship capital,” including children, because said investments can be zeroed out at any time (lowering marital fertility).

Affirmative action and state- and society-promoted education and career preferences for women, along with a welfare state responsible for large and direct impersonal wealth transfers from men to women outside of marriage. This greatly reduces the appeal of marriage for women, and effectively put the mechanism behind the Baby Boom into reverse.

Just as the driver of the First Demographic Transition was the moral legitimization of family planning, the Second was partly driven by the moral delegitimization of marriage. Marriage went from the institution that legitimized sex and children in the eyes of both society and the law to one lifestyle choice among many. This might seem like an advance in freedom, but the bigger effect was to misalign people’s short-term incentives and long-term interests. The vast majority of people prefer to raise children within stable, two-parent relationship, which marriage provides a framework for. By inverting the sexual incentive to marry (as chastity is not expected outside of marriage16 but fidelity is expected within it) and removing the legal privileges of children born within wedlock, the short-term incentives no longer push people to marry, but this makes it much harder for them as parents in the long run.

The First Demographic Transition was driven by falling marital fertility, and the Baby Boom by rising nuptiality. The second demographic transition was driven by both falling marital fertility and nuptiality.

After the initial collapse, several Western countries (Denmark, Finland, Sweden, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, plus the Anglosphere17) saw significant rises (>0.3) in TFRs from their lows over the next few decades (the Germanosphere saw a much smaller rise).

The reason this happened is a timing effect; some of the initial TFR collapse came from women delaying fertility. For biological reasons, fertility can only be delayed so far, and so when the pace at which women delayed fertility inevitably began to drop, TFR rebounded slightly18. Period fertility kept changing during this time, but cohort fertility was more stable. Is the marginally higher Western TFR of 2000 vs 1970 significant? When discussing the long-term outlook of a population, yes, because it’s TFR that matters. But when discussing individual behavior, cohort fertility is often the more relevant measure (because couples target a certain family size, even if they start later), and so this rise is less important.

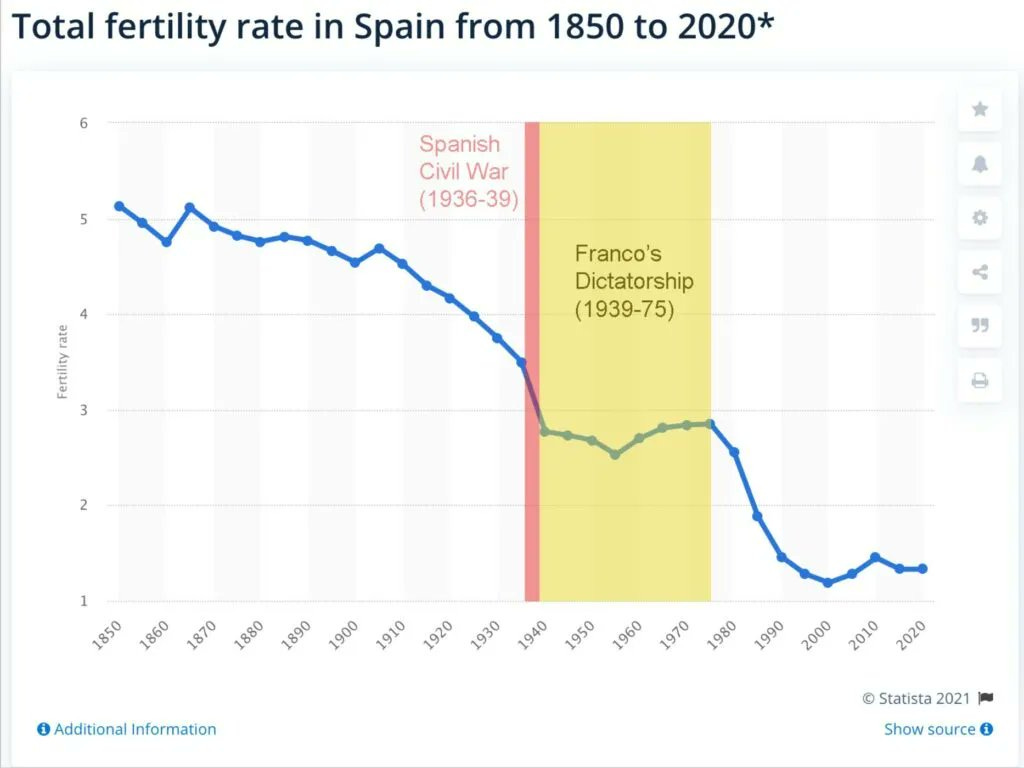

Spain

Spain provides a test case of my assertion. By putting the boot on Communist-adjacent New Left feminists, Franco froze in place Western norms around sexuality and marriage for a decade longer than they persisted in the core West. As expected, the post-(partial)-Baby-Boom collapse was delayed a decade in Spain.

Contraception and Abortion

Astute readers may notice that I don’t mention the Pill or legalized abortion. This might seem strange; isn’t cheap, effective, and convenient contraception the obvious explanation for the Second Demographic Transition? Why bother appealing to difficult-to-quantify cultural and legal changes when there’s such a clear technological answer?

The reason is simple: family planning is not a difficult problem. Even with the most common premodern solutions of abortion and infanticide taken off the table by Christianity, Western countries were able to reduce fertility to well below replacement in the interwar period with the same sorts of techniques that have been available since people first figured out where babies come from. Even if these techniques are unreliable and inconvenient on an individual level, they are more than sufficient on the population level.

There is the more sophisticated argument that the Pill caused the Sexual Revolution by enabling casual sex with minimal risk of pregnancy. Pre-pill methods of family planning require some level of foresight and typically the cooperation of both partners (and as such are difficult to use outside of long-term stable relationships such as marriage), while using hormonal birth control is trivial and can be used unilaterally by women without male input.

In this model, it’s not that modern contraception caused fertility collapse. Instead, modern contraception changed social norms to devalue long-term fidelity, which in turn caused fertility collapse. This is more plausible, but still wrong. These legal and social changes do not require technological backing. The Soviet Union went through most of them in the 1920s, legalizing unilateral divorce, homosexuality, and abortion, and giving illegitimate children the same status as those born one in wedlock. The extreme backwardness of rural Soviet society meant that these changes primarily affected the major urban centers. By the mid-1920s, more than half of Moscow marriages ended in divorce and abortions outnumbered births 3:1, 60 years before the US reached a comparable state. These changes were partially reversed by Stalin, who was concerned about the need for Soviet society to remain strong and populous in the fact of the German threat, in the 1930s19.

Japan

There is no Western country that went through the Sexual Revolution and second wave feminism without legalizing contraception, but Japan’s legal system and many of its social norms were forcibly aligned to the West after its defeat and conquest in the Pacific War. Like other fringe-Western cultures that had yet to go through the First Demographic Transition (Spain, Portugal, Italy, Quebec), it experienced a partial Baby Boom, wherein huge TFR declines were arrested (though not massively reversed) for decades, driven, like the true Baby Booms elsewhere, by increasing nuptiality. And like the West, it experienced both second-wave feminism and a Sexual Revolution, with the corresponding sharp fertility drop to well below replacement. Unlike the West, the Pill was not legalized until 1999. So Japan gives us an opportunity to check whether the technology or the social and legal revolution is more important.

If the Pill were the main driver of the Second Demographic Transition, either directly or through allowing for new social dynamics, we would expect little to no drop around 1970 and a clear drop in 1999, but the opposite is the case.

Recent Collapse

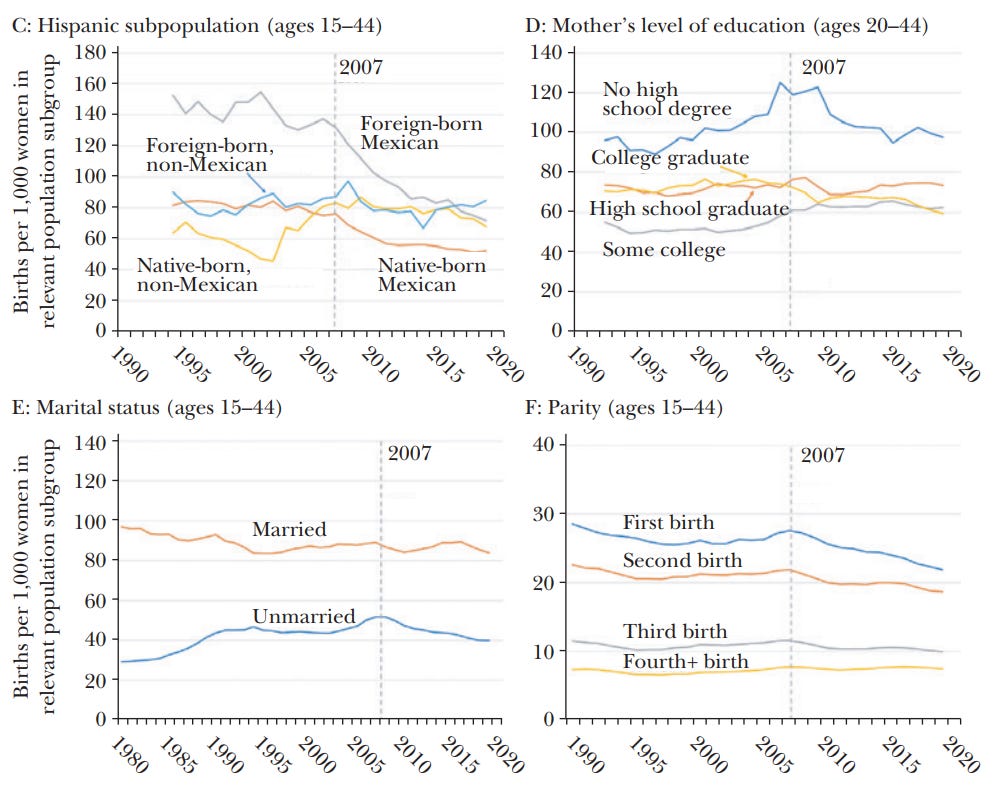

Characteristics: Fall from stably slightly below replacement-level to far below replacement-level fertility, driven by the young and low-IQ.

Proximate cause: Ubiquitous Internet leading to less unprotected sex, plus rising age at marriage hitting biological walls.

After several decades of approximate stability slightly below replacement, fertility fell sharply in most Western countries starting around 2012 (though the timing varies by country). Since 201520, US TFR has dropped by 0.22, Canada by 0.35, the UK by 0.32, Australia by 0.33, New Zealand by 0.50, Norway by 0.27, Denmark by 0.25, Sweden by 0.43, the Netherlands by 0.23, Germany by 0.14, Belgium by 0.26, Switzerland by 0.25, and France by 0.33.

This decline might look small compared to the previous wild swings, maybe too small to count as a separate stage, but it’s coming after decades of near-stability or slight rises. Most demographers did not see it coming, with the exception of a handful who thought carefully about the interaction of fertility age curves and delayed marriage. But even they mostly missed the proximate cause21.

The most important thing to grasp about recent Western fertility collapse is that it is concentrated among the lower class, the unmarried, the young (below 30), the uneducated, and recent non-Western immigrants. In other words, fertility is collapsing among the low-IQ and low impulse control.

Why? Some of this is that Charles Murray’s observation in Coming Apart that marriage was shifting from a society-wide institution to an upper class one22 is finally having the demographic impacts you would expect. Very few people23 want to raise kids alone or with a rotating series of unrelated partners, and modern contraception is convenient enough that almost anyone can use it. The rest is opportunity cost.

The big change around 2012, as with the Great Awokening, is ubiquitous Internet and smartphones24. What that means is that the opportunity cost for doing anything is much higher than before, because we always have the zero-marginal-cost, frictionless option of having fun online. It’s not the opportunity cost of children that matters here; marital fertility remains high and stable. It’s the opportunity cost of sex and (separately, though these are related) finding a husband or wife. Putting it crudely: rather than have unprotected sex or even dating seriously, teenagers and young adults are going online instead. There are more and more singles and singles are having fewer and fewer kids.

I list this as the final (for now) stage of the Western fertility story, but the exact same phenomenon is occurring in Latin America and is responsible for the sharp collapse of Latin American fertility since about 2012.

Conclusions

If there’s one big takeaway from all of this, it’s that very few people saw any of these phase changes coming before they happened. It can be easy for pronatalists interested in demography to doom about the strong negative trends of the past half-century, but things can and have changed fast, in both directions. The future is malleable.

I specify “net” because falling infant and child mortality is easily the single biggest thing that affects TFR. But this doesn’t much matter if family sizes remain constant.

When I say “Western,” I mainly mean the Anglosphere, the Germanosphere, France, the Low Countries, and the Nordics. These countries all got wealthy early and are characterized by the Western European Marriage Pattern, low kinship intensity, and high levels of achievement. All of these countries are culturally (long histories of Western Christianity), genetically, and historically similar. Italy, Iberia, and Quebec are all fringe-Western, being comparatively backwards both economically and socially until after WWII, but converged with the “core West” in the 20th century. Japan is not Western, but has a similar history (early industrialization, US side of the Cold War) and its convergence with Western social and legal norms as a result of WWII makes it a useful comparison.

See The WEIRDest People in The World by Joseph Heinrich for a book-length treatment.

This is one of the big differences between Imperial Japan and the pre-60s West. Western divorce rates were low and required some level of fault. Imperial Japan, on the other hand, had the highest divorce rate in the world. However, divorce was almost entirely a prerogative of the husband, which means a very different set of incentives from those created by post-60s divorce law and family courts.

With the funny exception of a brief period in the 19th century when a number of German states banned marriage among the poor to try to reduce the strain on public resources. But the exception proves the rule: even under these conditions, illegitimacy only reached 14% at the highest.

TFR is calculated by constructing an imaginary woman who experiences the age-specific fertility of women in a given population between the ages of 15 and 49 at a certain point in time (you can think of this as constructing a woman who experiences the life cycle fertility typical of her population in a single year).

Marital TFR is calculated by constructing an imaginary woman who experiences the age-specific fertility of MARRIED women in a given population between the ages of 15 and 49 at a certain point in time. A marital TFR of 8.6 does NOT mean that the average married couple had 8.6 children, because very few women get married at 15 and remain married through age 49. The vast majority of married women marry later, don’t remain married through their reproductive years, or both.

For similar reasons, regular TFR inflates the fertility of premodern societies because significant numbers of women died between the ages of 15 and 49.

Source is A Farewell to Alms, page 73.

Quebec, culturally isolated from France by British rule and culturally isolated from the Anglosphere by the French language and deliberate insularity, managed to avoid the First Demographic Transition altogether.

I’ve seen some wrong interpretations of this paper circulate on Twitter/X, so here’s where I point out that the main effect of the Bradlaugh-Besant trial was to morally normalize family planning, not provide contraceptive techniques or technologies (the techniques in the relevant pamphlet being broadly ineffective). See the Bradlaugh-Besant section of “Mind Viruses: In Defense of an Analogy” or read the paper itself for details.

Nuptiality just means the frequency and characteristics of marriage in a population. A common measure is the fraction of women aged 15-50 married, ranging from 0-1. Earlier, more frequent, and more stable marriages can all increase nuptiality.

The extreme example of this is Mexico in the 1960s, which had a net (not gross) TFR of 6, comparable to ultra-Orthodox Jews today, for the entire country. This is why 1960s Mexico, with very little immigration, dominates the list of most rapidly growing countries in history.

I’ve seen claims that the post-WW1 loss of Western cultural self-confidence or First Wave feminism, which reached its apogee in these years, are responsible for Western fertility dipping as low as it did. These claims are probably partly true (source: gut feeling), but I think these are very clearly secondary to the First Demographic Transition, which in turn is down to family planning. Maybe Western fertility would have remained above replacement in the 1930s without early feminism or WW1, but it still would’ve been a phase-change from the default Western European Marriage Pattern.

From the memoirs of Hungarian physicist Eugene Wigner (via Gwern):

Once I asked my father, “Why are people so attached to money?” He responded simply, “Because of the power and influence it gives them.” I disliked this bit of cynicism and told him so. It was years before I saw that he was largely right: The human desires for power and influence are very deep and strong. I learned a great deal from my father which I failed to fully credit at the time. These talks with my father led me to wonder, “Why am I on this earth? What do I want to achieve?” I felt my purpose should be to marry, to begin my own family, and to provide this family with a proper home and nourishment. Today, these things come far more easily and many youths no longer know what to strive for. Many of them see power and influence as the only valid goal. But in 1919, providing a home and nourishment was a valid purpose.

The US and France were somewhat anomalous in that they saw big increases in marital fertility in addition to increasing nuptiality.

I use “cultures” and not “countries” intentionally. The first demographic transition was more cultural than legal.

Of course, this was always somewhat honored-in-the-breach. In 1953 Italy, about a sixth of brides were pregnant at the time of marriage (Castiglioni and Zuanna 1994). But these exceptions prove the rule; pre-Sexual Revolution, having sex served as an incentive to quickly marry, with long-term benefits to both individual and society.

The US saw a bigger rise, reaching replacement in 2007, because of the massive Hispanic (mostly Mexican) Baby Boom triggered by the 1986 IRCA (Hispanics in 2008 had a TFR of 2.9, with Mexican-Americans at 3.1). But culturally and genetically distinct recent immigrant diasporas are going to follow different patterns, and the Great Financial Crisis ended Mexican-American fertility exceptionalism, so this doesn’t change the broad Western picture. Something similar is the case with Arab and African immigrants in France. Both US whites and ethnic French were on the high side of Western fertility during this period and remain so to this day, but not by nearly as much as national TFRs would suggest.

For a more thorough explanation of this phenomenon, see Demographic explanation for the recent rise in European fertility by Bongaarts and Sobotka. The same phenomenon is at work with post-90s Eastern Bloc fertility rebound.

The USSR then went through another Sexual Revolution in the 1960s, again without much modern contraception (abortion being the contraceptive method of choice).

2015 chosen because that’s where @BirthGauge’s numbers start. The decline begins a few years earlier.

A fun game is comparing MacroTrends numbers, which use UN population projections from a few years ago, with actual up-to-date numbers from @BirthGauge. With the exception of Afghanistan, where Taliban takeover seems to have stalled the decline, MacroTrends numbers are uniformly too high.

In part because the welfare state replaces most of the economic functions of marriage for lower classes, and in part because no fault divorce + family court hell + low impulse control and high time preference is a really terrible combination. Society no longer tries to make marriages work; it does its best to incentivize breaking them up instead. Maintaining a stable marriage is now the sole responsibility of husband and wife, which raises the bar for making it work, a lot. In the long run, people follow incentives.

When writing about fertility or marriage I make a deliberate effort to use gendered terms (men, women, husband, wife), because this is the area where sex differences are most important. Here I use “people” rather than “women” intentionally. Too much fertility discussion focuses exclusively on women and women’s incentives and desires, to the exclusion of men.

And dating apps.

Arctotherium has the clearest analysis of historical demographic and fertility trends and their causes of anyone I've read.

This is a tremendous overview. Some points or observations I want to add:

1. I've seen several charts for English TFR in the early 19th century showing a peak around 1820, as opposed to around 1840 in Blanc's chart that you're citing. Blanc is more recent, so I suppose more reliable, but I'll just point out this difference and I'm not sure what the cause is.

I also recall evidence that early-industrializing Britain was an early adopter of modern sanitation practices and consequently began to see improvements in childhood mortality in the Victorian Era, down into the 30-40% range; the ~50% number remained stubbornly persistent even in most of Europe throughout the 1800s. This gave further gas to the British population explosion. Though IIRC the drop to ~0% throughout the industrialized world mainly occurred in the period 1900-1950 or so.

2. If we gloss over the hiccup around 1930, we might call the period 1910-2010 "The Century of 2-3 Western TFR". I think the fertility story of that century remains very *culturally* impactful; it's when the image was established of what a family in an industrial, urban society looks like, and this is why many leftists and normies struggle to update and recognize the reality of a fertility crash. The 2-3 TFR century encompasses, for example, virtually the entire history of film and television. The popular imagination says that 2 kids are normal, 3 kids are normal-plus, and while some people have 0-1 kids, they are generally going to be canceled out by those with 3 and the occasional weirdos with 4+, such that population continues to increase.

This was a good enough approximation of reality during that century if you average out the decades, but we're now clearly outside that paradigm.