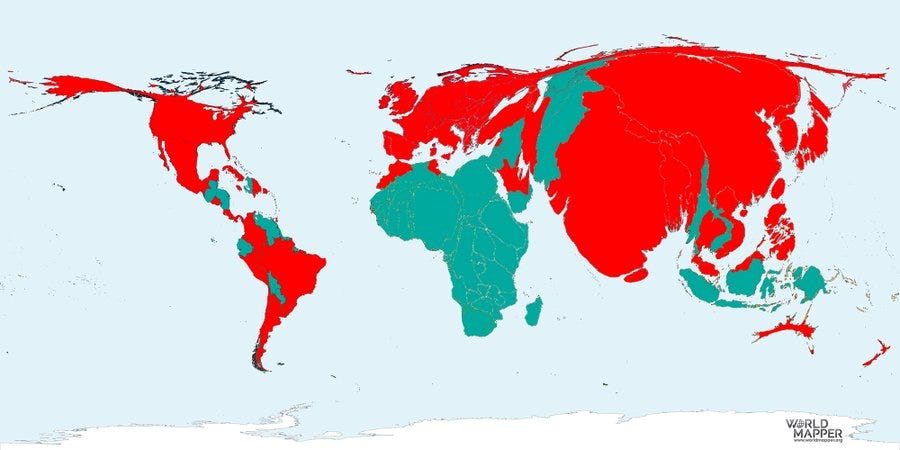

Since the beginnings of the First Demographic Transition in 1760s France, there has been a near monotonic decrease in fertility rates in affected countries, which now include every country on Earth. Birth rates in most of the Western world have been well below replacement for two generations. It seems like the inevitable price of modernity; today, almost every country in the world is facing the same problem. Pro-natal policies from Hungary to South Korea have barely even slow this trend.

Fertility decline has many predictable downsides. Aging populations means pension crises, lowered growth and innovation, and gerontocracy.

Below replacement fertility means declining group power1 and lowered individual fitness2. In the long run, it means extinction or conquest by younger and more numerous invaders. It is a very bad thing to have happen to your society.

But this isn’t the first time this has happened. Many Western countries had below replacement fertility in the 1920s and 1930s after decades of rapid fertility decline. Demographers predicted this would continue and foresaw a future of stagnation, decline, and weakness against the rising tide of color. They were wrong.

The Baby Boom

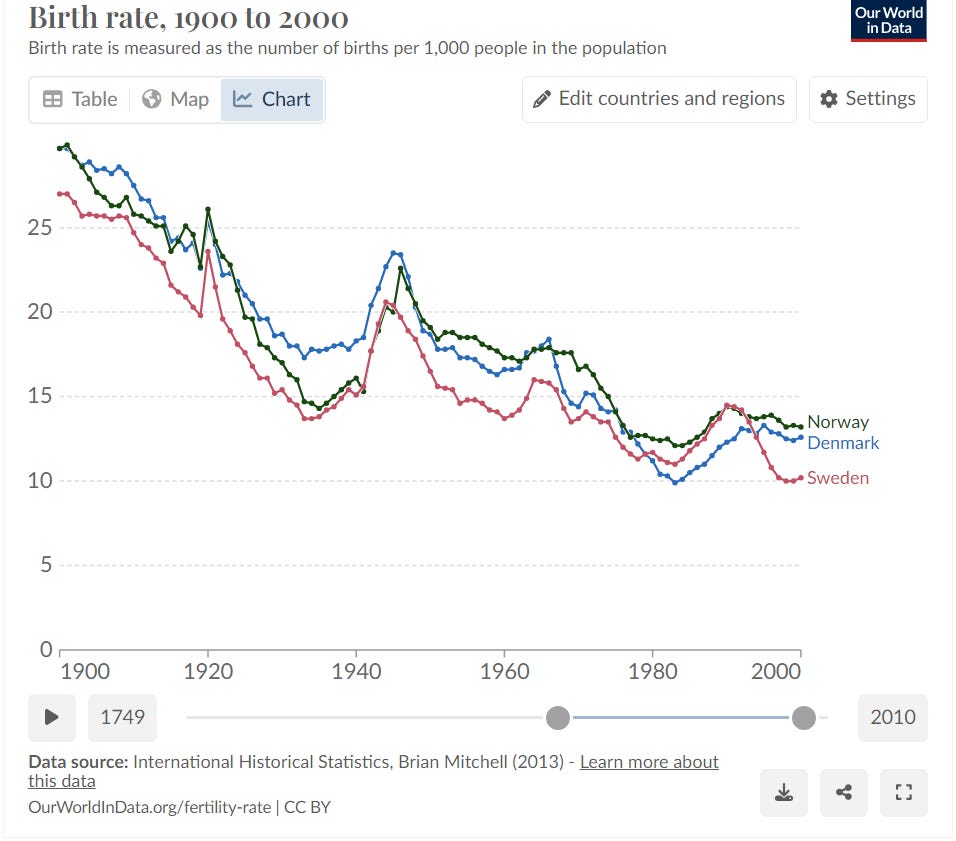

The Baby Boom was the sudden rise in fertility, beginning in the late 1930s, of the wealthiest and most advanced countries in the (Western) world. It is often associated with the end of World War II, but actually began before then (and, in many countries, was partially interrupted by hostilities). These countries include the Anglosphere (Ireland, United Kingdom, United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia).

The Nordics (Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Iceland).

The wealthy continental European countries, occupied but victorious in World War II (France, Netherlands, Belgium).

And the German-speaking countries (Germany, Austria, Switzerland), which mostly lost World War II.

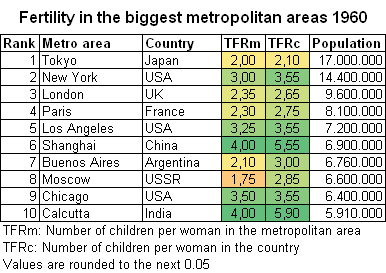

All of these countries had previously undergone the First Demographic Transition to a regime of lower mortality and lower (near or below replacement) fertility3. This list does not include semi-industrialized societies that had not fully undergone this first transition, such as those of Eastern (except Czechoslovakia) and Southern Europe, Japan, and Quebec, nor does it include the Third World4.

What stands out about it?

The Baby Boom took place in what were, at the time, the wealthiest, most technologically advanced, longest lived, most urban, most educated, most individualist, and most scientifically sophisticated societies in human history, by a wide margin. And it took place during a time when all of these metrics (except maybe individualism) were very rapidly improving.

Many theories of fertility decline claim that it is the inevitable result of various good things: technological advancement, wealth, education, science (through weakening religion), urbanization, individualism, and declines in childhood mortality. Since (almost) no one really wants to go back to being high mortality, low-tech, extremely poor, rural, and ignorant, the story goes, we simply need to live with it. There is good empirical evidence for all of these things mattering, but what the Baby Boom shows is that it is possible to have it all. You can have a rich, rapidly growing, technologically sophisticated, personally free and individualist, urban, long-lived and fertile society. There’s no need to choose between slow extinction and preindustrial poverty.

The Importance of the Boom: Net Fertility vs Gross Fertility

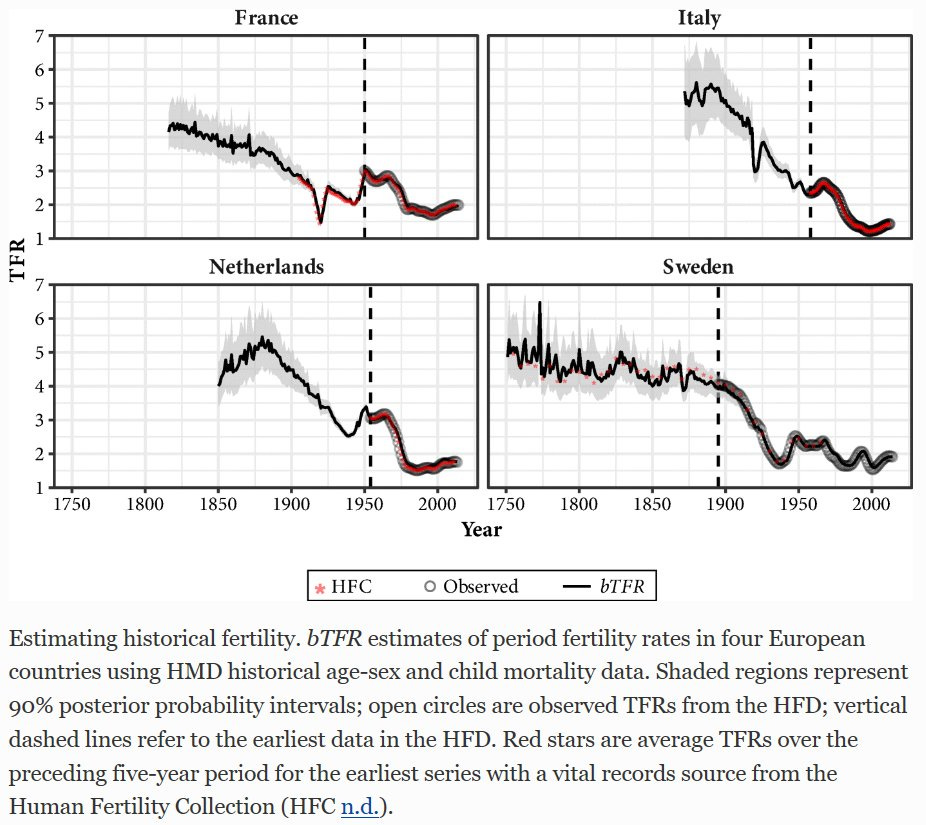

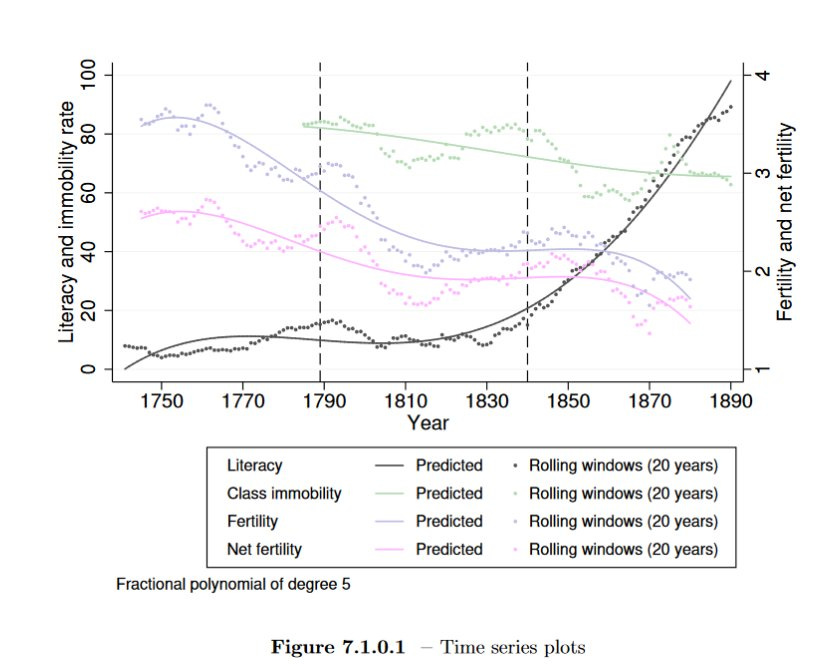

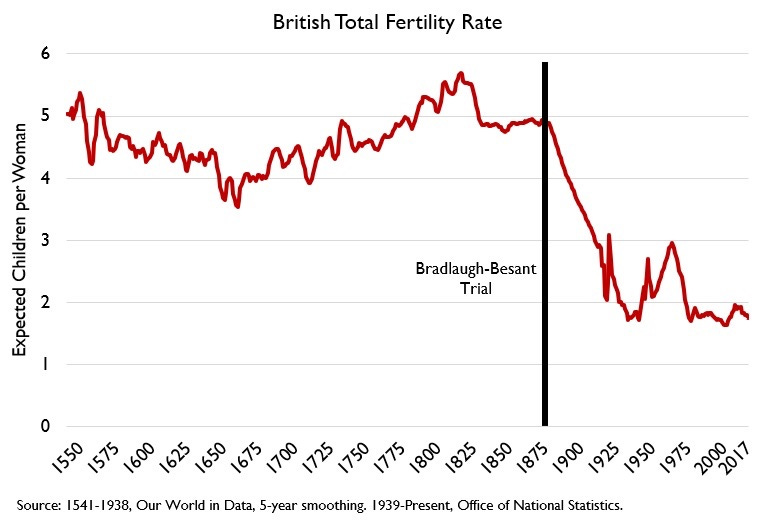

Most discussions of fertility focus on total fertility rate (TFR, calculated by assuming women experience current age-specific fertility rates throughout their lifetimes and live through their reproductive years) or crude birth rate (births per woman per year). Historic graphs of Western fertility using these metrics tend to look like this:

This gives the false impression that, while the Baby Boom was significant for the 20th century, it was only a blip compared to the massive fertility decline preceding it. This is misleading. TFR works well for 20th century Western countries, and for most of the world past World War II. But it falls apart when dealing with countries with high infant and childhood mortality, as was universal before the late 19th century.

What we really care about is net fertility, that is, the number of children surviving to adulthood. Net fertility data is harder to come by then crude birth rates or TFR, but measures for advanced Western countries do exist. They generally look like this.

Once Malthusian constraints are lifted by the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions, you have a near-constant net fertility at around three, before a major decline in the early 20th century to around replacement5, followed by a major resurgence to around the original level during the Baby Boom.

The important exception is France, which went through its demographic transition about a century ahead of the rest of the Boom countries, probably for cultural reasons.

But French net fertility also recovered to its pre-transition level during the Baby Boom, with French population growth peaking in 1965.

In effect, the Baby Boom completely undid the First Demographic Transition. This is approximately what “natural” Western fertility looks like when not under severe economic stress (historical default) or subjected to anti-natal culture and laws.

What is the Baby Boom pattern?

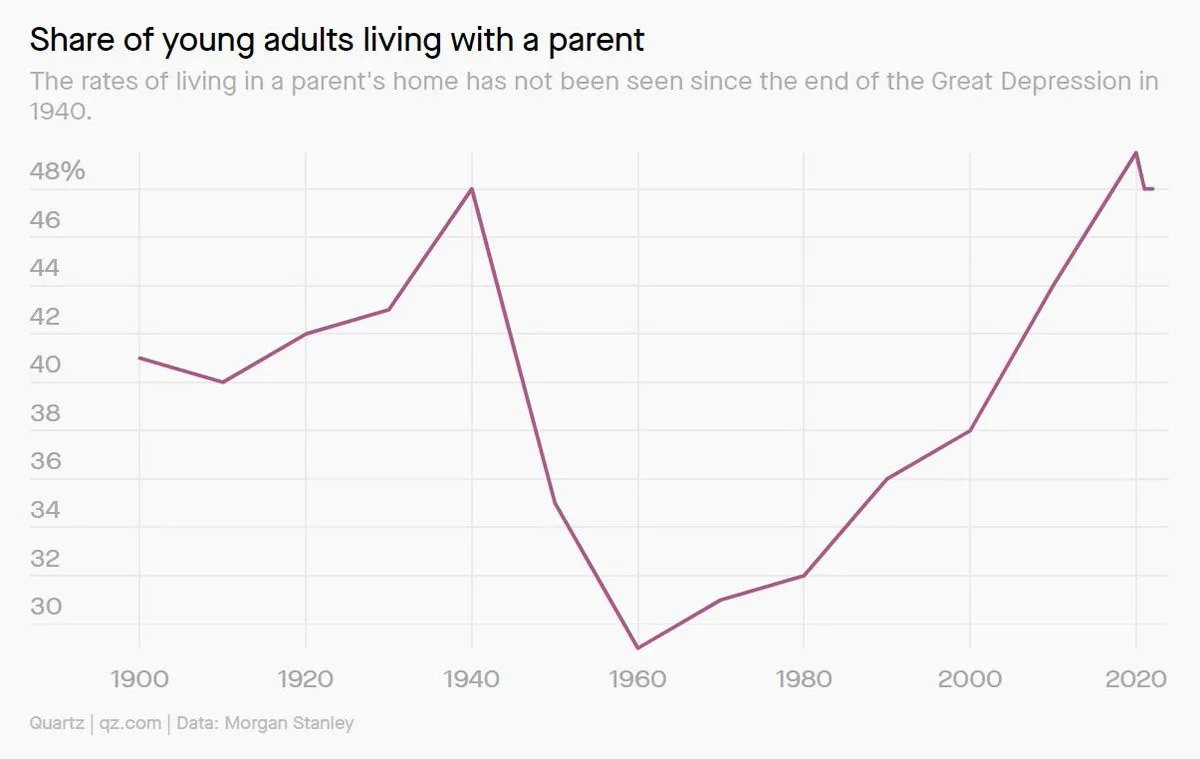

There are many social science graphs that look a lot like the Baby Boom fertility graphs. That is, you see a deterioration of some metric in the late 19th or early 20th century, followed by a sudden improvement in the 1930s or 1940s, which continues until around 1970 or so, when there is a rapid return to the pre-improvement level, usually followed by further deterioration. Here are some examples for things other than fertility rates (though many are obviously related).

Twitter mutual Mythean calls this pattern6 a “sadly ephemeral period of mass nuclear virtue,” and postulates that this general phenomenon was caused by the rigors of World War II.

This pattern explains most 1950s nostalgia.

Non-explanations for the Boom

There are several popular, but wrong explanations for the Baby Boom. These come up in almost any discussion of the Baby Boom, so it is worth debunking them.

Generational income levels. In this model, popularized by Richard Easterlin, large cohorts lead to lower wages (relative to expectations) leading to low fertility leading to small cohorts leading to high wages leading to high fertility. This would be convenient, since it would suggest population would naturally reach an equilibrium and thus long-term population aging and decline is not a problem. It might even have been plausible in 1978 when it was proposed, but has completely failed since then, with small, post-Boom cohorts across Europe having lower fertility than ever. It has also been refuted by showing that cohort effects (birth year) don’t particularly matter for the beginning of the Baby Boom, with it instead being explained by period effects (changes during the Baby Boom rather than changes in the years those who participated in the Boom were born).

Household appliances and antibiotics. In this model, recently popularized by Works in Progress, household appliances popularized after WWII reduce the costs of childbearing and antibiotics reduce the risk of various STDs as well as reducing maternal mortality. Since incentives matter, the story goes, easier and safer childbearing means more births. This would be very convenient (all we need is rapid economic growth, which we want anyways!) but has the twin problems that the size of the Boom was inversely correlated with appliance rollout and the beginning of the boom predates the fall in STDs. Also, this model predicts you should see Baby Booms in every country when appliances and antibiotics first spread, but that didn’t (doesn’t) happen. The vast majority of the world only had (or is having) a single demographic transition, rather than the double-transition pattern of the Boom countries.

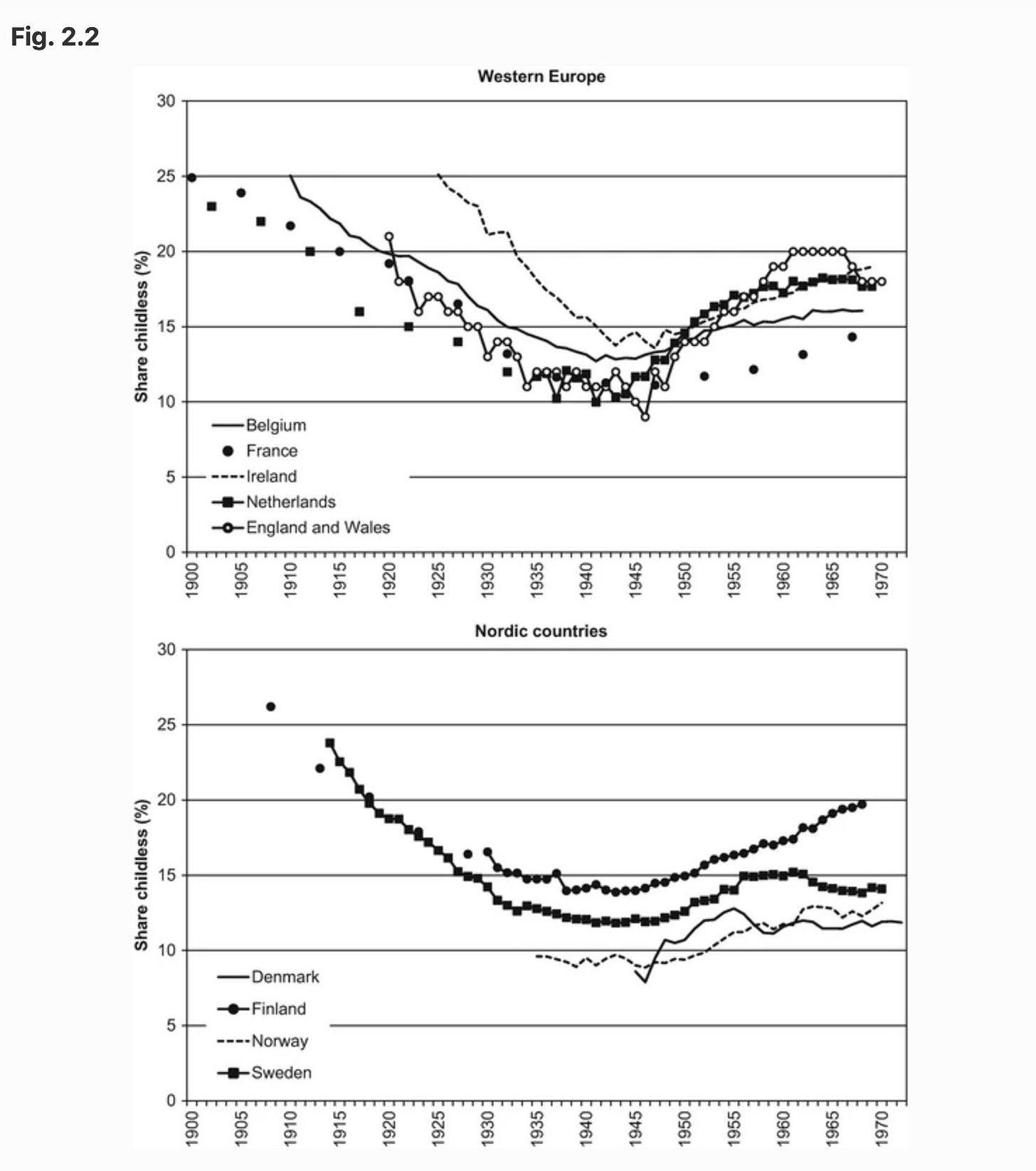

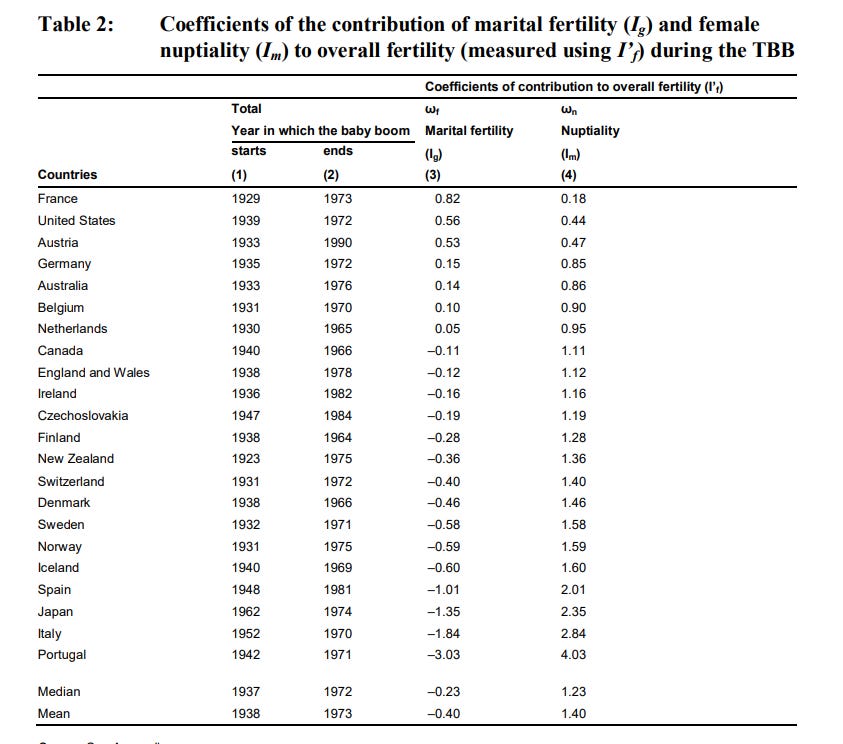

Contraception failure. In this model, the Baby Boom is just a marriage boom combined with an inability to practice fertility control due to ineffective contraception. This would not be very convenient, since it suggests that the only way to revive the Boom is to imitate Ceaușescu’s Romania, which (almost) no one wants. The trouble with this hypothesis is that it is quite easy to practice fertility control on a population-wide scale using low-tech methods, as shown by the fact that the Demographic Transition began in pre-industrial France and had already spread to all of the Boom countries by 1920 (or the fact that Japan, famously the world leader of low fertility for decades after WW2, didn’t legalize the Pill until 1999). Furthermore, marital fertility actually declined in many Boom countries during this period, suggesting married couples got better, not worse, at controlling their fertility.

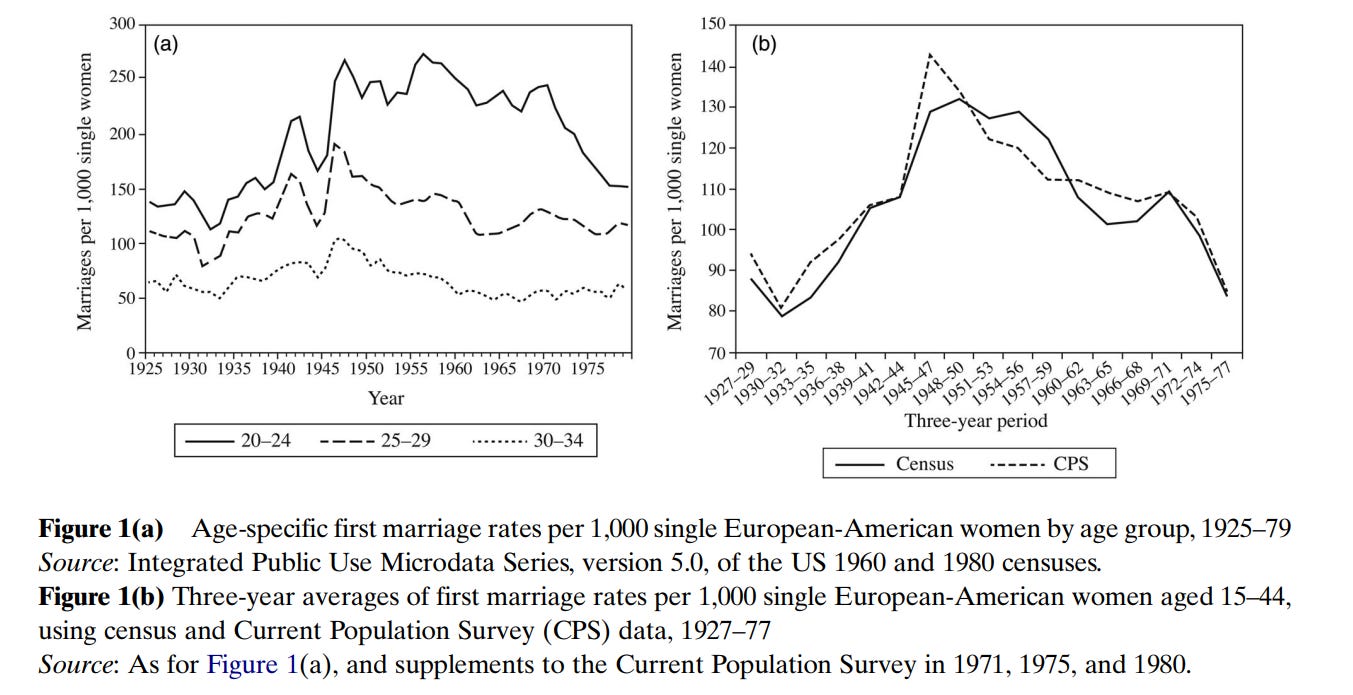

The Baby Boom is a Marriage Boom

The proximate cause of the Baby Boom is not a mystery. Almost all births during the Baby Boom were within wedlock, meaning that fertility was a function of (1) nuptiality and (2) marital fertility. In 15/22 countries (8/15 if excluding Southern/Eastern Europe, Ireland, and Japan), marital fertility actually decreased during the Baby Boom, meaning that the entire Boom is explained by more marriage. Only in the US, France, and Austria does marital fertility increase explain more than 15% of the Baby Boom, so when looking at it as a West-wide pattern, we can effectively reduce the Baby Boom to a marriage boom: more people getting and staying married at younger ages.

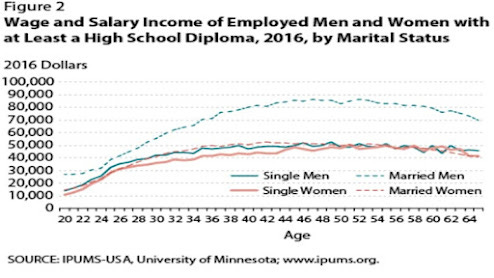

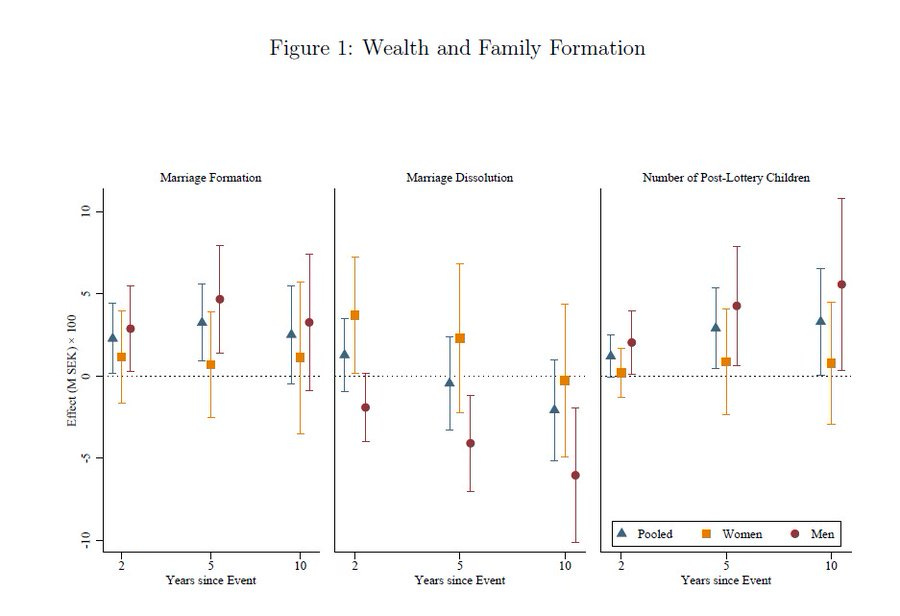

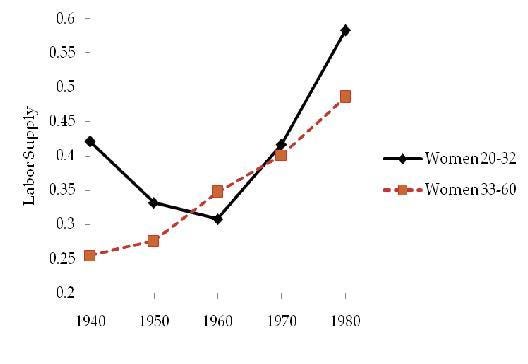

So what caused this marriage boom? The answer appears to be a rise in young men’s status compared to young women’s7. The marriage boom can be explained almost entirely by a combination of female labor force participation (down), young male wages (up), and male unemployment (down).

This model actually understates the case, because it uses total female labor force participation, rather than the relevant variable, which is labor force participation for young women. An overall decline in female labor force participation masks the fact that there was actually an increase in female labor force participation among older women (in part due to World War II; women who got jobs in factories while men fought often stayed after the war), which in turn drove down wages (and thus labor force participation) among younger women.

Wages are not the only way to measure status. After briefly reaching parity at the zenith of first wave feminism, young men during the Baby Boom again greatly exceeded their female counterparts in educational attainment.

Note that what matters here is relative gains, not absolute gains. Women did not make less money and were not less educated in 1960 as compared to 1930, merely less so in comparison to their male peers.

The mechanism here is clear: young women want money and status, young men have relatively more money and status, women can get men’s money and status by marrying them. Marriage leads to babies, and thus the Baby Boom.

What ended the Baby Boom?

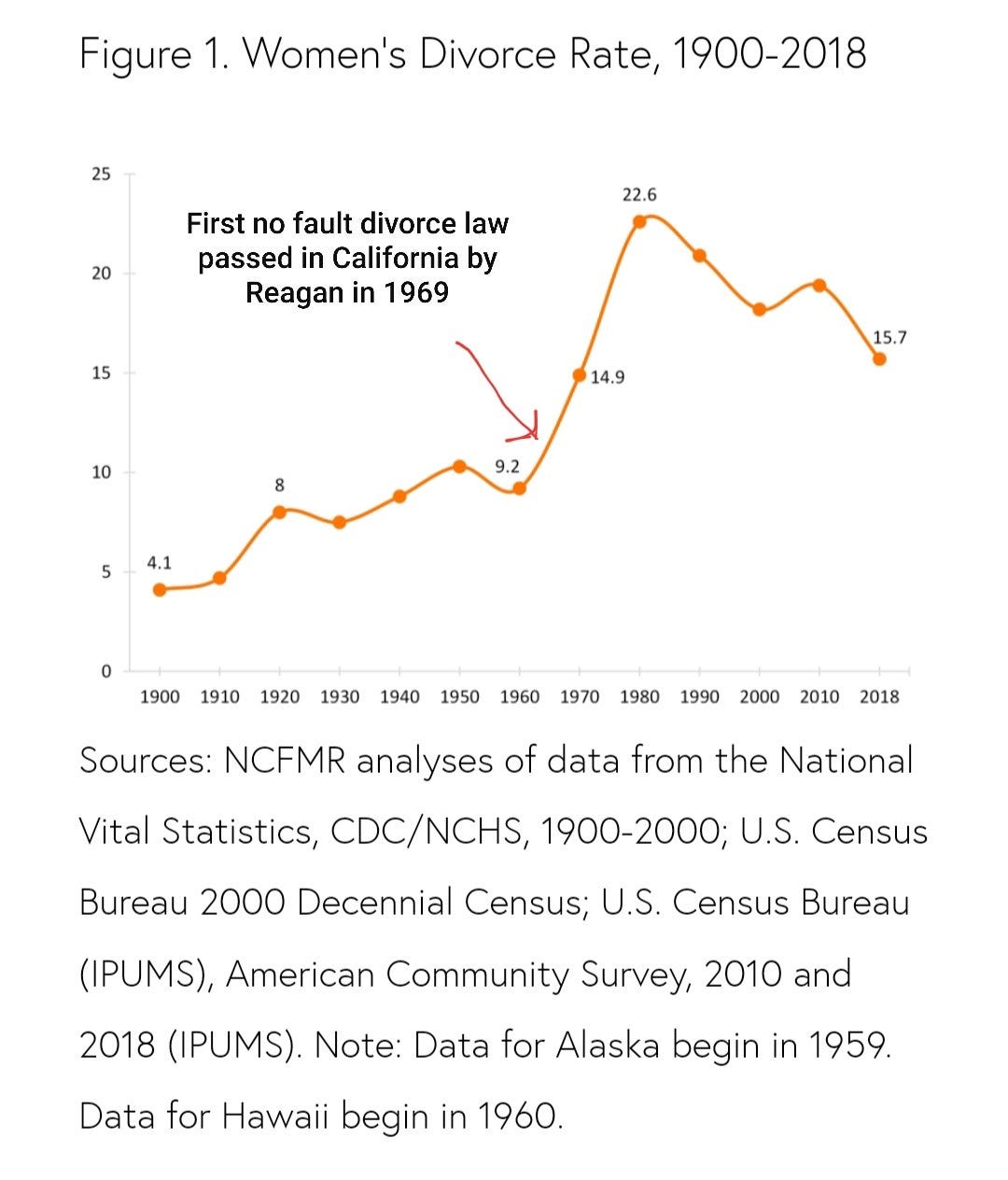

In three words: second wave feminism. By this I mean the suite of changes referred to as the Sexual Revolution (no fault divorce, normalization of premarital sex, delegitimization of marriage as the normative form of the family), combined with a concerted political campaign to raise women’s relative economic and social status. Fertility in every Boom country, as well as in several countries that didn’t experience the Boom but had slightly above-replacement fertility (such as Italy and Japan), cratered within a few years around 1970 (the time of the social and legislative triumph of second wave feminism) to well below replacement, and never recovered. But what are the precise mechanisms?

The most common answer is the Pill, which made cheap, effective, convenient contraception widely available. But this is highly confounded with second wave feminism, because this movement pushed for its legalization. Where you see second wave feminism and not the Pill, as in Japan, you see the same decline around 1970, and no further drop once the Pill is legalized8.

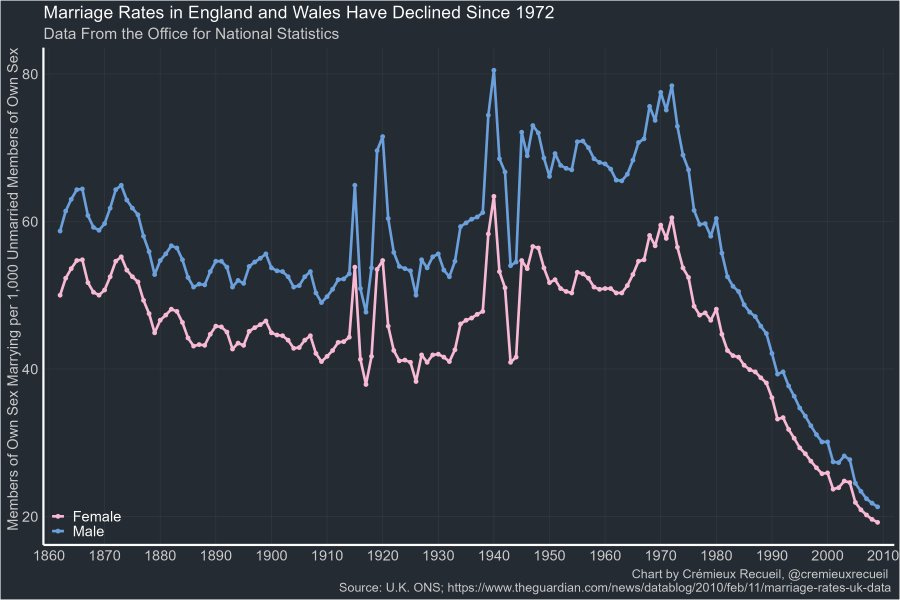

The Baby Boom was mostly a marriage boom, so the obvious explanation is the subsequent marriage bust.

The marriage boom was entirely explicable in terms of a rising (young) male economic advantage, so how has that advantage changed since 1970?

It’s worth noting that this is not just a natural consequence of the shift from an industrial to a service economy. Affirmative Action in favor of women is common across the Boom countries, as is disproportionate female employment in state-created regulatory jobs such as HR. There are also thousands of organizations explicitly dedicated to promoting women’s careers at the expense of men’s, and almost none of the converse. These combine to artificially raise women’s wages above the market rate, and lower men’s.

But we don’t just have wages to consider, we also have taxes and transfers. Thanks to progressive taxation, men pay the vast majority of taxes while women receive the vast majority of benefits. Since married men are the most productive, while single women are the poorest (on a per-household basis), this is predominantly a transfer from married men to single women. This makes marriage less attractive to women; they can get men’s money for free, courtesy of the government, without having to give anything in return. The state serves as a surrogate husband.

But young men’s vs young women’s economic status is not the only factor determining marriage rates. It fully explains the boom, but not the bust. The explanation lies in the fact that second wave feminism thoroughly redefined marriage. It shifted from a patriarchal institution in which husbands had social (and some legal, though this was mostly dismantled by first wave feminism) power over their wives to one in which wives had effective legal power over the husbands (through the mechanisms of feminist family courts, greatly expanded definitions of abuse, and the replacement of the marriage model of the family with the child support model), and from a lifelong contract to one dissolvable at will (though the institution of no-fault divorce). In JD Unwin’s terms, we shift from a regime of absolute monogamy to one of modified monogamy. This had obvious and immediate consequences on marriage rates.

The mechanism through which no-fault divorce reduces marriage rates is simple. No-fault divorce eliminates the promise of lifelong commitment, greatly reducing the benefits of marriage for both parties. The other partner can bail at any time, for any reason. This particularly increases the costs for men through the mechanism of family courts (as divorce usually means he loses his assets, income, and children).

Unfortunately, this tidal wave of divorce did not even have the effect of making those marriages that survived happier.

There was also a suite of social changes, which are more difficult to quantify but nonetheless real. During the Sexual Revolution, premarital and extramarital sex went from heavily stigmatized (particularly for women) to generally accepted. This naturally reduces the benefits (for both men and women) of marriage, as it is possible to have socially-accepted sex outside of the institution.

In the US, the form of marriage has hung on among the upper middle class, but the substance has been hollowed out. In much of Europe, even the form is almost gone, replaced by cohabitation (which lacks pre-60s marriage’s implicit promise of stability).

What is to be done?

Here is a short list of ideas suggested by this analysis of the Baby Boom. Many of them are compatible with conservative and libertarian principles, and could be pushed democratically.

Roll back the welfare and pension state and lower income taxes. The transfer of hundreds of billions of dollars a year (in the US) from men to women artificially harms men’s relative economic status, which in turn harms marriage prospects.

Roll back the regulatory state. Women tend to be overrepresented both in government jobs like teaching and in jobs created by government regulation like HR, which artificially inflates their wages relative to their market value.

End Affirmative Action for women and ban (or de facto ban, as similar lobbying organizations for men are) the thousands of organizations, scholarships, and programs that exist to promote women’s career success (particularly in the best compensated and highest status jobs) at the expense of men.

Defund education. Women outperforming men in education seems to be a universal feature of the modern world. This high performance is not matched by corresponding real-world success, meaning that girls are relatively better at school then they are at learning or applying that knowledge. There may be ways of eliminating or reversing this pro-female bias in the school system, but I’m not aware of any successful attempts. But that doesn’t mean nothing can be done. The signaling model of education (see Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education) implies that education is mostly (~80%) a zero sum game, meaning that reducing it across the board would be a benefit. Defunding higher education (and ideally public education) entirely would reduce education across the board, making it less attractive and important for both men and women.

Pronatalist monetary incentives should be targeted at married husbands, rather than mothers. If it must be done in a sex-neutral way, then do it in the form of income tax breaks, as married men make the most money and pay the most income taxes. Almost all actually existing incentive programs reverse this, thus reducing women’s incentives to marry.

Roll back the Sexual Revolution. This is easier said then done, and probably can’t be done with legislation alone (see: many failed Roman attempts at undoing their version of the Sexual Revolution). It would look like bringing back slut-shaming (perhaps via the colossal American media/propaganda apparatus, which the Romans did not have), ending no-fault divorce9, encouraging young marriage as the default life path, and generally making the married nuclear family the normative unit of society again.

There is no need to accept demographic decline as the price of prosperity. We have beaten it before. We can beat it again!

Further Reading

Study on the causes of the beginning and end of the Baby Boom: https://sci-hub.se/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00324728.2016.1271140

Study on the relative importance of marital fertility versus nuptiality in explaining the Baby Boom: https://www.demographic-research.org/volumes/vol38/40/38-40.pdf

Study on the effects of differential education on fertility during the Baby Boom, focused on Belgium. It shows that hypergamous marriages (husband more educated) were generally higher fertility then homogamous or hypogamous marriages, and that the Baby Boom reduced the negative correlation between education and female fertility (thus reducing dysgenics): https://www.cairn.info/revue-annales-de-demographie-historique-2016-2-page-139.htm

Article on the increasing male wage advantage during the Baby Boom: https://cepr.org/voxeu/columns/more-babies-europe-lessons-post-war-baby-boom

Various Dalrock articles on the decline of the benefits of marriage for men (https://dalrock.wordpress.com/2012/10/06/debasing-marriage/), the inability for the modern state to really incentivize men to marry, because it misunderstands why men marry and why married men are more productive (https://dalrock.wordpress.com/2014/12/21/the-unworkable-bachelor-tax/), and how the welfare state effectively socializes husbands (https://dalrock.wordpress.com/2012/10/15/how-the-destruction-of-marriage-is-strangling-the-feminist-welfare-state/). Much of his blog is relevant.

Which can matter a lot; consider the impact of low 19th century French fertility on the course of both World Wars. And of course, in a multiethnic democracy, population is power, and you want your group to have more children so that your interests are better represented in government (see the Revenge of the Cradles for a historic example).

Even if you yourself have more than two kids, fertility is affected by social factors, and your kids in turn are much less likely to replace themselves in a low-fertility society.

There is very good evidence that people adjust fertility downwards in response to lower infant and childhood mortality so as to keep family sizes constant. Outside of a handful of breeder cults, this is practically an iron law of fertility. But this only explains part of fertility declines, as we’ll see.

In order of size of boom, we have, roughly, the overseas Anglosphere, followed by Britain, France, the Nordics, and the Netherlands, followed by the German speaking countries and Belgium, which has important consequences even today for the demographic structure and relative importance of these countries [1].

And in many cases, below: TFR of 1930 Vienna was around 0.7, until 2022 the lowest recorded peacetime fertility of any major urban area in history. And it wasn’t alone!

Note that this is a distinct phenomenon from other common patterns in social graphs, such as the “everything breaks around 1970” pattern of continuous improvement from the Industrial Revolution until around 1970 (many graphs at https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/), the monotonic change since the Industrial Revolution pattern (many good things, such as life expectancy and GDP per capita, some bad things, such as dysgenics), and the “Great Awokening” smartphone/social media-driven pattern of a sharp break around 2010 (also seen in things like mental health).

Please note that this is not a fully general explanation for marriage or fertility rates, which are demonstrably affected by dozens of different things, only for the Baby Boom as a unique and important historic episode.

Furthermore, there is a very important country that saw a Sexual Revolution and second wave feminism before Boom countries did: the Soviet Union, which (Communism being ideologically feminist) made very similar social changes (no-fault divorce, elimination of taboos against premarital sex, elimination of taboos against bastardry, legalization of homosexuality) in the 1920s. The 1920s Soviet Union was desperately poor and was decades from the invention of the Pill, but nonetheless saw skyrocketing divorce and cratering TFR.

Doing this by itself would almost certainly backfire by making marriage even less attractive. It needs to be combined with the rest of the package to work. Unfortunately, it is also the easiest to accomplish legislatively, while the others require at least a successful propaganda campaign and probably a full blown social upheaval on the level of the 1960s.

This is the most important article I have read in recent memory. It identifies a huge social problem and offers solutions.

Nice one!