Review of J. D. Unwin's Sex and Culture

The Importance of Sex Relations to Cultural Achievement

Introduction

What causes the rise and decline of nations? Geography? Climate change? Returns on complexity? Eugenics and dysgenics? Asabiyyah? These are critical questions to understanding the past and predicting the future. It is impossible to run experiments on history, and so the only available method to answer them is induction. As it happens, there is an extraordinarily comprehensive inductive survey that unintentionally answered this question nearly a century ago.

J. D. Unwin was an early 20th century Oxford anthropologist who published his magnum opus, Sex and Culture, in 1934. His goal was to evaluate the psychological proposition that restraints on sexual activity led to sexual energy’s sublimation into social energy. To that end, he conducted an inductive survey of the sex relations and social energy of 80 uncivilized societies as well as the Sumerians, Babylonians, Hellenes, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, and English, with a few comments about the Arabs and Moors. This survey was necessarily limited to those societies on which he had reliable evidence, and so could not be exhaustive, but does not appear cherry-picked; he explains why he does not include notable societies (such as China) in his survey and the limitations of his method, and encourages the reader to test his conclusions on societies on which he did not have sufficient evidence and via alternative measures of social energy. Despite his careful hedging, he nevertheless comes to an extremely strong conclusion: that changes in and levels of social energy are deterministically caused by sex relations, and that the course of society can thus be predicted (and perhaps controlled) by changing these.

Unwin’s Model

Unwin defines human energy as the exercise of those powers which are exclusively human, namely the “power of reason, the power of creation, and the power of reflecting upon itself.” The cultural process then, “consists of the use of these powers, which are potential in all human organisms,” but not universally or evenly applied. To Unwin, all individuals have the capacity to display this energy, but only some societies do so. Unwin divides the social display of this energy into two categories, expansive and productive. Common examples of expansive social energy are “territorial expansion, conquest, colonization and the foundation of a widely flung commerce,” while a society manifesting productive social energy “develops the resources of its habitat and by increasing its knowledge of the material universe bends nature to its will.” Expansive social energy is more common then productive; all societies that display productive social energy first went through a period of expansion, but not all expansive societies become productive.

Unwin furthermore defines human entropy as the innate ability to refine and enrich a cultural tradition, appearing only after a new generation is born into a society of great energy, and refers to an increase in “human entropy” as the Direction of the Cultural Process. Confusingly, unlike actual entropy, there is no tendency for human entropy to increase without limit; it usually disappears within a given stratum of society within half a generation of its first exhibition. Likewise, the Direction of the Cultural Process can be, and always is eventually, reversed.

Unwin distinguishes between civilized and uncivilized societies, but this not a key portion of his model, which would work even without this distinction. In his own words:

When I speak of 'civilized' societies I refer only to the following sixteen historical peoples: Sumerians, Babylonians, Egyptians, Assyrians, Hellenes, Persians, Hindus, Chinese, Japanese, Sassanids, Arabs (Moors), Romans, Teutons, and Anglo-Saxons (i.e. ourselves). According to my terminology any society not included in this list was 'uncivilized'. It is a rough, arbitrary classification. The cultural condition of some uncivilized societies was, of course, higher than that of some of the civilized peoples.

This divide serves as an aid to comprehension rather than a load-bearing part of the model and matches our intuition as to the meaning of civilization.

Rather than attempt to classify societies based on their beliefs, which can be difficult for outsiders to ascertain and which cannot always be translated across cultural lines, Unwin classifies them based on their rites into four categories: zoistic, manistic, deistic, and rationalistic. Unwin defines societies who build temples as deistic (note the architectural definition, rather than one based on beliefs), those who do not build temples but pay post-funeral attention to their dead as manistic, and those who do neither as zoistic. In general, deistic societies have a longer historical memory and display more energy than manistic ones, which in turn have a longer memory and display more energy then zoistic peoples. Rationalistic societies are those which display productive energy; Unwin describes a rationalistic society like so:

It changes its ideas on every conceivable subject, increases its mental range, and expands in all its multifarious activities. Its method of treating sickness is altered in accordance with its new knowledge; by using the inherent power of reason it formulates and applies its knowledge of the physical universe; it produces more than it consumes, thus creating capital; it unearths new sources of wealth which less energetic societies neglect; it discovers new ways of treating old materials, bends nature to its purpose, and assumes a mastery of the earth.

On the grounds that rationalistic societies have the greatest control over their environment, Unwin classifies rationalistic as the highest cultural state. Since all rationalistic societies were deistic prior to becoming rationalistic, he puts deistic next on the scale. Since many deistic societies have cults of the dead, manistic is placed below deistic, with zoistic lowest of all. But there is no fixed progression between them; with the exception of requiring a deistic society before a rationalistic one, a society in any cultural condition can reach any other, without intermediate steps. Furthermore, it is important to note that complex societies are composed of different stratums of people, which can fall into different categories. Unwin classifies complex societies based on their dominant stratum.

When a society ascends in the cultural scale, some sections of the people retain their old opinions and remain in the lower cultural condition. Then the society is divided into two cultural strata. Indeed, the higher a society ascends the greater is the difference in the culture of the various strata, the number of those strata depending on the nature of the rise of the society. In a deistic society which passed direct from the zoistic into the deistic condition, there would be a zoistic as well as a deistic stratum; in a rationalistic society we may find a deistic stratum, and/or a manistic stratum and/or a zoistic stratum, according to the manner in which the most developed stratum emerged.

Unwin defines sexual opportunity as “the opportunity which is afforded to a man or a woman to gratify a sexual desire.” Sexual opportunity is limited when “the sexual regulations prevent such satisfaction; the impulse must be checked or the offender will be punished.” Sexual continence is defined as when sexual opportunity is checked.

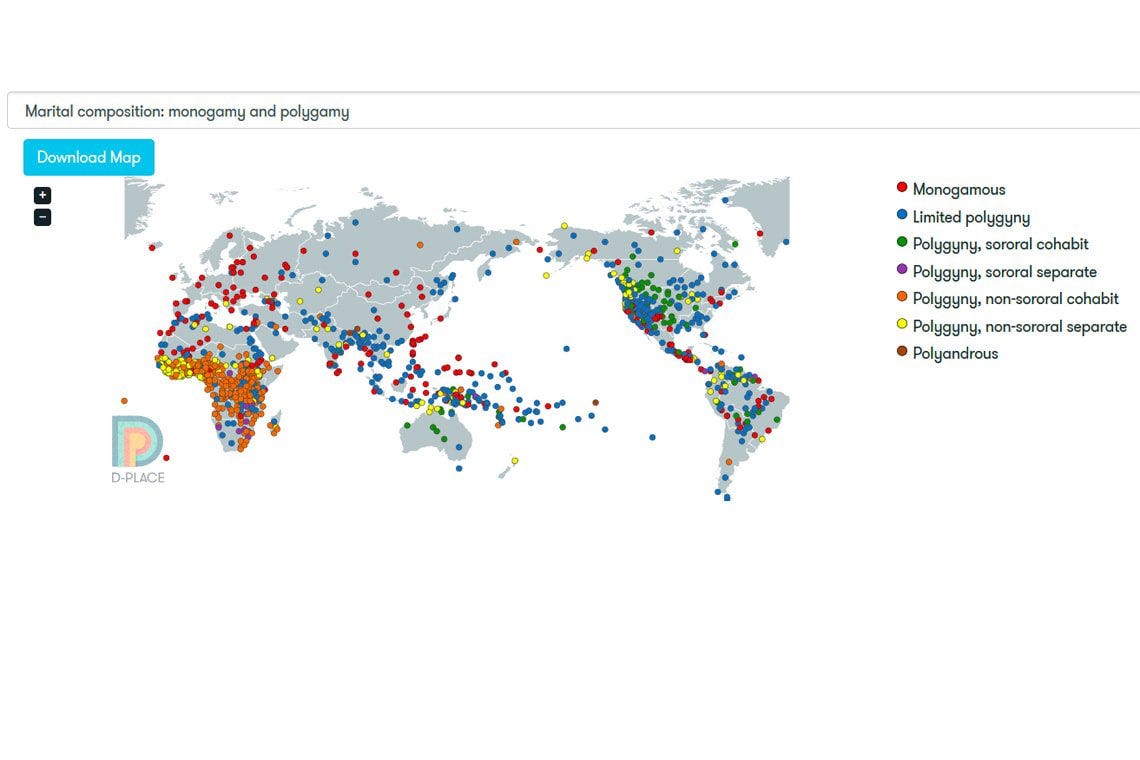

Unwin divides sex relations into seven categories; three referring to sex relations before marriage, and four to the structure of marriage. The first group is as follows:

Pre-nuptially (1) men and women may be sexually free, (2) they may be subject to regulations which compel only an irregular or occasional continence, (3) under pain of punishment and even death the women may have to remain virgins until they are married.

The four classes of marriage are defined like so:

Modified monogamy—the practice or circumstance of having one spouse at one time, the association being terminable by either party in accordance with the prevailing law or custom;

Modified polygamy—the practice or circumstance of having more than one wife at one time, the wives being free to leave their husbands on terms laid down by law and custom;

Absolute monogamy—the practice or circumstance of having one spouse at one time, but presupposing conditions whereby legally the wife is under the dominion of her husband and must confine her sexual qualities to him, under pain of punishment, for the whole of his or her life;

Absolute polygamy—the practice or circumstance of having more than one wife at one time, these wives being compelled to confine their sexual qualities to their husband for the whole of their lives.

Post-nuptial regulations are only relevant if pre-nuptial regulations demand absolute chastity. In order of least to most sexual continence, the various categories are thus:

1) Pre-nuptial sexual freedom.

2) Irregular or occasional pre-nuptial continence.

3) Women compelled to be virgo intacta when they join their husbands.

4) Modified monogamy or polygamy.

5) Absolute polygamy.

6) Absolute monogamy.

Note that (3) must be combined with (4), (5), or (6).

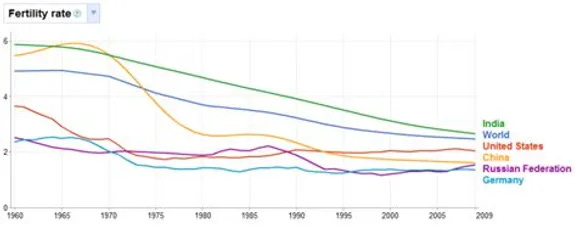

It’s important to remember that no energetic society’s sex relations are static; consider the revolution that has taken place in the United States since 1960. This is not an anomaly. As Unwin writes:

I view with alarm the current habit, deplorably widespread among historians and antiquarians, of assuming that the regulations and conventions that prevailed in a century of which we have direct knowledge prevailed also in a preceding or in a succeeding century, of which we may have no direct knowledge at all. Whenever our knowledge is complete, we find that in any vigorous society the method of regulating the relations between the sexes was constantly changing; and, unless there is direct evidence, it is wrong to assume that in any such society social laws were ever static and unchanging, even for three generations.

With terms and categories defined, what did Unwin find?

Unwin’s Findings

The cultural condition of any society in any geographical environment is conditioned by its past and present methods of regulating the relations between the sexes.

There is a perfect correspondence between sexual continence and cultural category. All zoistic societies permit pre-nuptial sexual freedom, and all societies that permit pre-nuptial sexual freedom are zoistic. All manistic societies require irregular pre-nuptial continence, and all societies requiring irregular pre-nuptial continence are manistic. All societies requiring pre-nuptial chastity (among women) are deistic, and all deistic uncivilized societies require pre-nuptial chastity. All uncivilized peoples fall within one of these three categories. Every deistic uncivilized society fell within group (4) above (modified polygamy or monogamy); there were no uncivilized absolute polygamists or monogamists. On this basis, Unwin formulates his three secondary laws of culture as such:

The first secondary law is this:

Any society in which complete pre-nuptial sexual freedom (outside the exogamic regulations and prohibited degrees) has been permitted for at least three generations will be in the zoistic cultural condition. It will also be at a dead level of conception if previously it has not been in a higher cultural condition.

The second secondary law is this:

If in any human society such regulations are adopted as compel an irregular or occasional continence, the cultural condition of that society will become manistic. If the compulsory continence be slight, the post-funeral rites will partake of the nature of tendance. If it be great, they will partake also of the nature of cult.

The third secondary law is this:

If in any human society the girls of an uprising generation are compelled to be pre-nuptially chaste, that society will be in the deistic cultural condition. If a zoistic culture be inherited, the same power will be manifest in all temples. If a manistic culture be inherited, different powers will be manifest in different temples.

Unwin’s most important finding is this: a decrease in sexual opportunity always leads to greater social energy; conversely, an increase in sexual opportunity always leads to less social energy. This applies within societies as well as between them; if different strata have different norms, the most stringent strata will be the most energetic and come to dominate society. There are some qualifiers. The sexual opportunity of men only matters if the sexual opportunity of women has already been reduced to a minimum. In other words, if a society is absolutely polygamous, absolute monogamy leads to greater social energy, but additional restrictions on male sexuality in a non-absolutely polygamous society do not. Absolutely polygamous societies can display great expansive energy for a short time, but never display productive energy or become rationalistic unless they marry wives reared in an absolutely monogamous tradition (as happened with the Moors in Spain who married Christian and Jewish wives). From this, Unwin concludes that the sexual opportunity of women is more important than that of men, although both are required to reach the highest peaks of culture. Furthermore, only absolutely monogamous societies display great energy for extended periods and conversely, every absolutely monogamous society displays great energy.

Every rationalistic society was absolutely monogamous for several generations, with the aforementioned explained exception of the Moors in Spain, however absolute monogamy alone does not suffice to produce this state. Many absolutely monogamous societies display great expansive energy, then relax their regulations without ever becoming rationalistic. Only those societies which retain absolute monogamy for several generations display rationalistic culture and productive energy, and only those few that maintain that state for an extended period manifest human entropy. Unwin thus formulates his second primary law of human culture like so:

No society can display productive social energy unless a new generation inherits a social system under which sexual opportunity is reduced to a minimum. If such a system be preserved, a richer and yet richer tradition will be created, refined by human entropy.

But as societies are not homogeneous, the same strictures do not need to apply to every element within them, only to at least one social stratum:

There is no need for the whole society to suffer the same continence. So long as the sexual opportunity of one social stratum is maintained at a minimum, the society will display productive energy.

As one might expect, the full effect of a change in sexual opportunity is not seen overnight. It takes three generations, or about a century, for the full implications to manifest themselves. It is both past and present sex relations, not just present ones, that determine the nature of a society. This is because the habits and attitudes formed by the previous regime are maintained in the first generation and passed on in diluted form to the second. It is only the third generation that is wholly formed under the new rules. High culture and sexual freedom can coexist, but only for one generation.

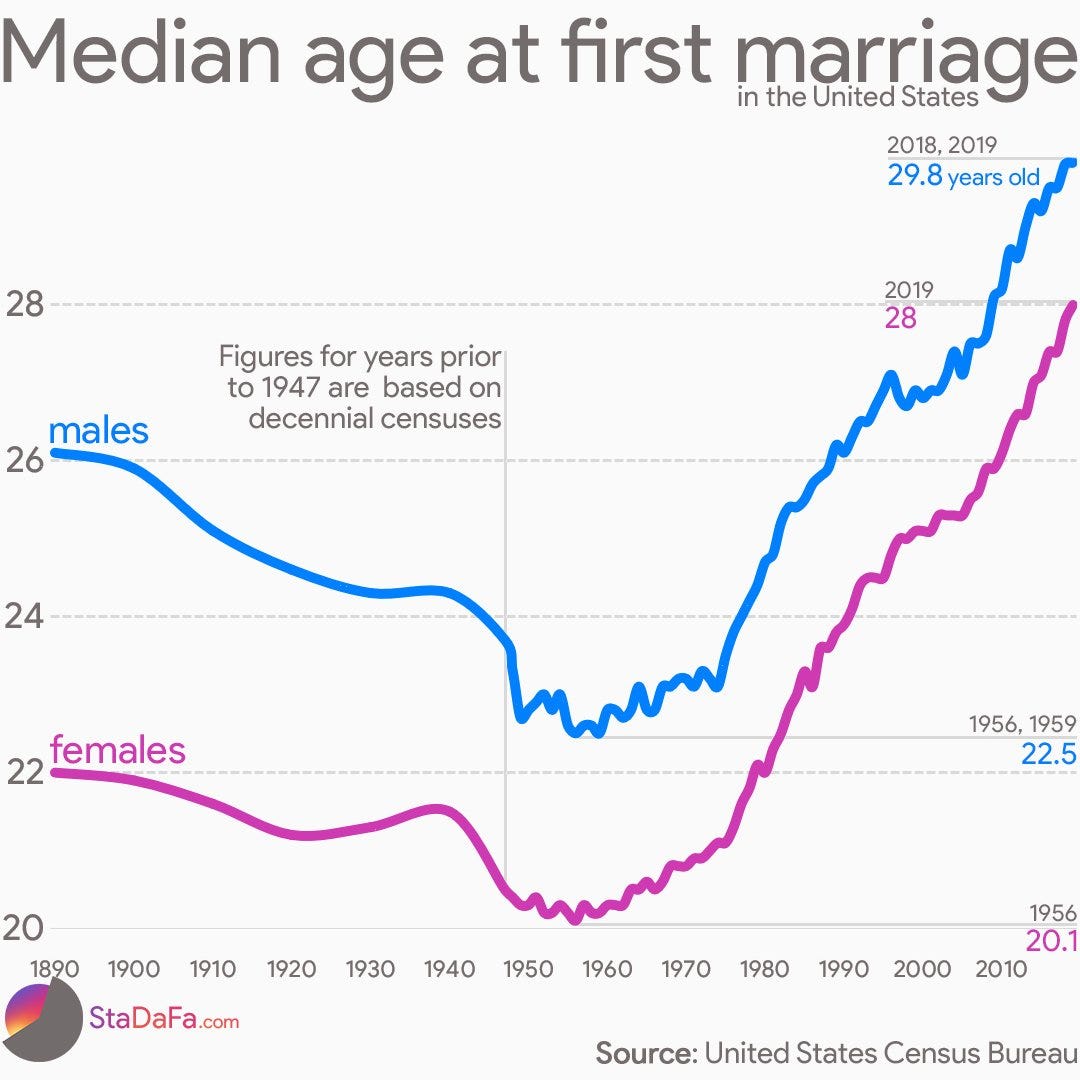

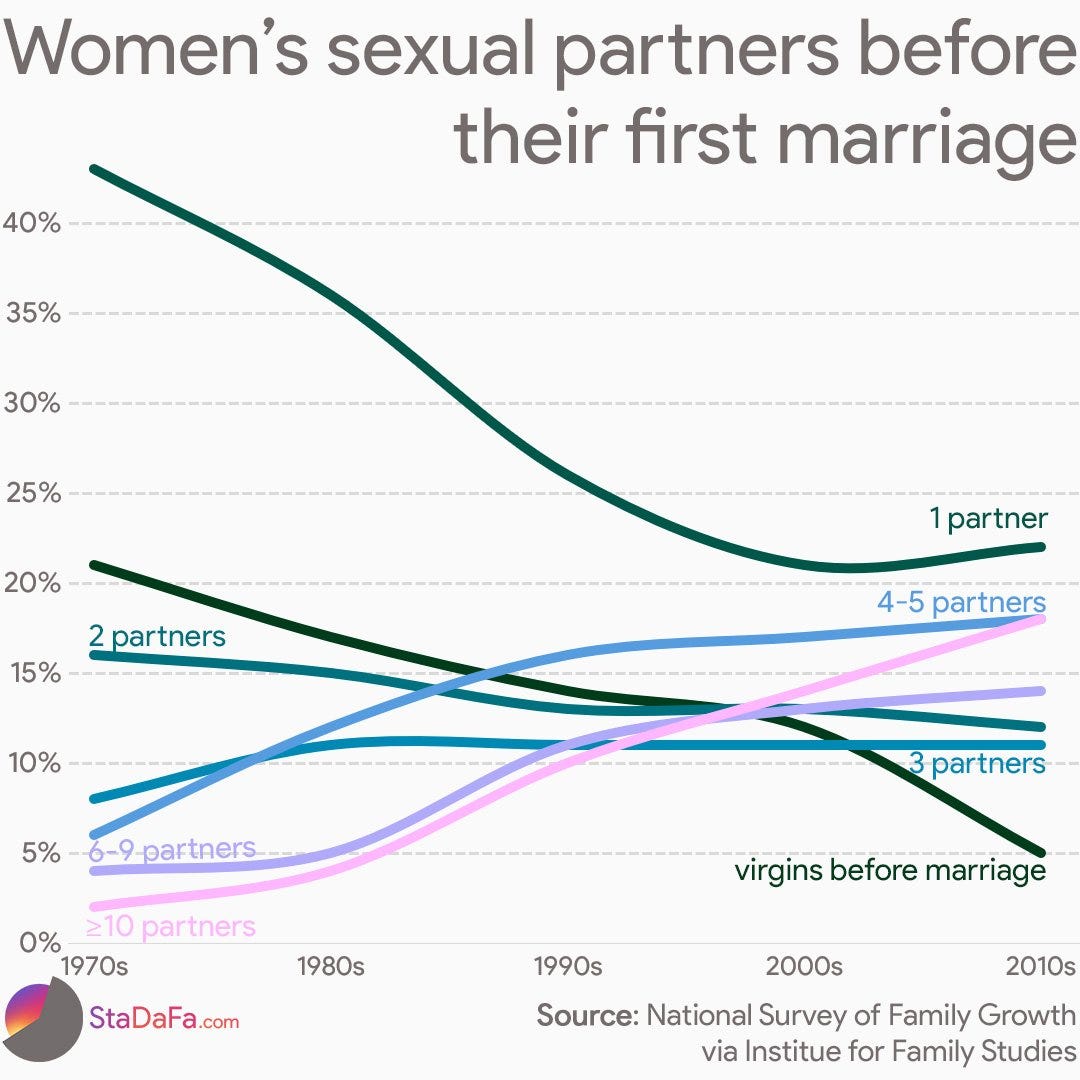

Absolute monogamy is an extraordinarily rigorous institution, and has only ever been established via the complete subjugation of women to their husbands; that is, their relegation to the status of a legal non-entity, interacting with society only as an element of their father or husband’s household. Furthermore, the process by which absolute monogamy is first modified, then abolished is the same in every society, reoccurring again and again with “unrelieved monotony.” First, women are emancipated from their husbands and granted co-equal status. Then, marriage is altered from a lifelong commitment to a “temporary union made and broken by mutual consent,” transitioning from absolute to modified monogamy. In most cases, societies cease to demand prenuptial chastity. After three generations, societies cease to display energy, becoming inert, and are often conquered by more energetic neighbors. The same sentiments (Unwin mentions the idea that women are naturally virtuous), struggles, changes, and results always ensue.

Sometimes we imagine that we have arrived at a conception of the status of women in society which is far superior to that of any other age; we feel an inordinate pride because we regard ourselves as the only civilized society which has understood that the sexes must have social, legal, and political equality. Nothing could be farther from the truth. A female emancipating movement is a cultural phenomenon of unfailing regularity; it appears to be the necessary outcome of absolute monogamy.

Applying Unwin’s Findings to a Novel Case: Japan

If Unwin’s findings are robust, they should apply to a case of which he had little knowledge. An obvious test of his thesis is that of Japan, by generations the first nonwhite country to successfully adapt to the Industrial Revolution, which after centuries of stagnation displayed incredible expansive energy between the Meiji restoration and its defeat by the United States in WW2 and impressive productive energy in the postwar decades (albeit much of this was simply copying Western innovations), before a return to stagnation in the 1990s.

Shortly before the Meiji restoration, “the institution of marriage among the common citizenry was more ‘flexible,’ with people easily marrying and remarrying after divorces.”1 In other words, it was in a state of modified monogamy. It was stricter among the nobility, as predicted by Unwin’s model, but still did not reach the rigor of absolute monogamy. In 1870, the Meiji government established that marriage meant the wife being absorbed by the husband’s family, rather than a coequal, mutually dissoluble partnership. This was further strengthened by the Civil Code of 1898, which codified the new norm that “wives had no legal rights over family matters, such as parental or property rights.” These changes established absolute monogamy as the law of the land in Imperial Japan, corresponding to Japan’s extraordinary period of expansion. The beginnings of the dissolution of absolute monogamy can also be seen, with “women’s magazines in the Taisho Era (1912-1926)” writing “special features calling for more ‘free marriages,’” but these tendencies were successfully opposed by the government. It was the sons of this era that conquered half the Pacific Rim and built modern Japan after WW2.

Both absolute monogamy and Japanese expansion came to a crashing halt with its conquest by the United States. The 1946 Constitution imposed by the Americans “stipulated that a marriage takes effect solely by agreement between a man and a woman,” but the idea of marriage as a lifelong commitment with male authority was still the norm until the early 1970s, with only 20% of Japanese believing that an unhappy couple should divorce in 1972. This serves as a reminder that these changes do not occur overnight, and that while ideas, customs, and laws typically change around the same time, they don’t have to. The energy of Japanese society, while not zero (which per Unwin would take three generations), is clearly declining, with population decline and economic stagnation. Thus, the history of modern Japan supports Unwin’s model.

How Do Unwin’s Findings Hold Up Today?

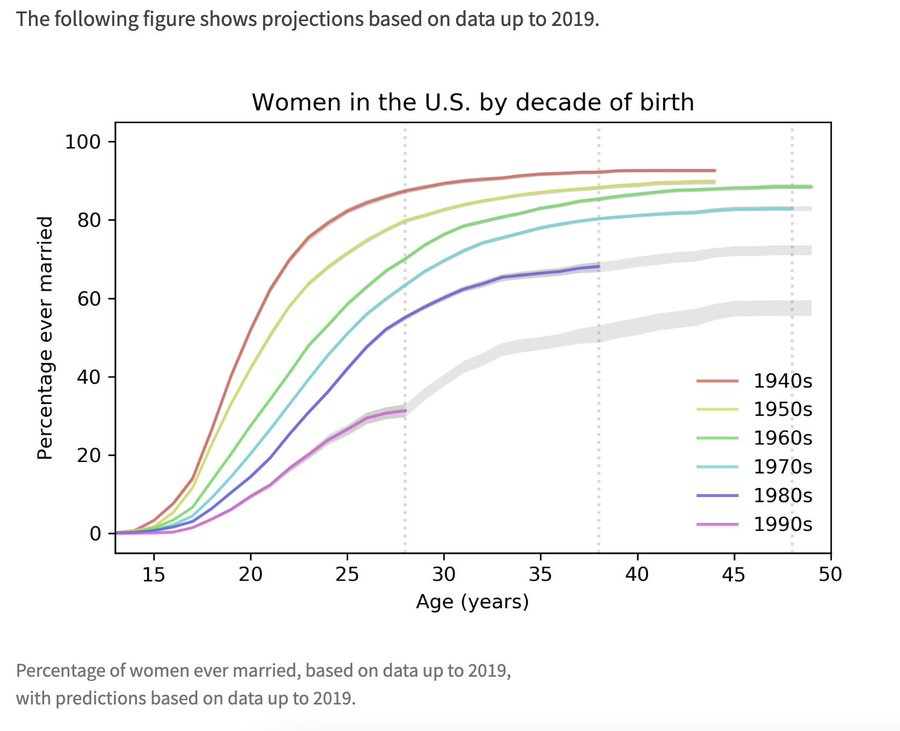

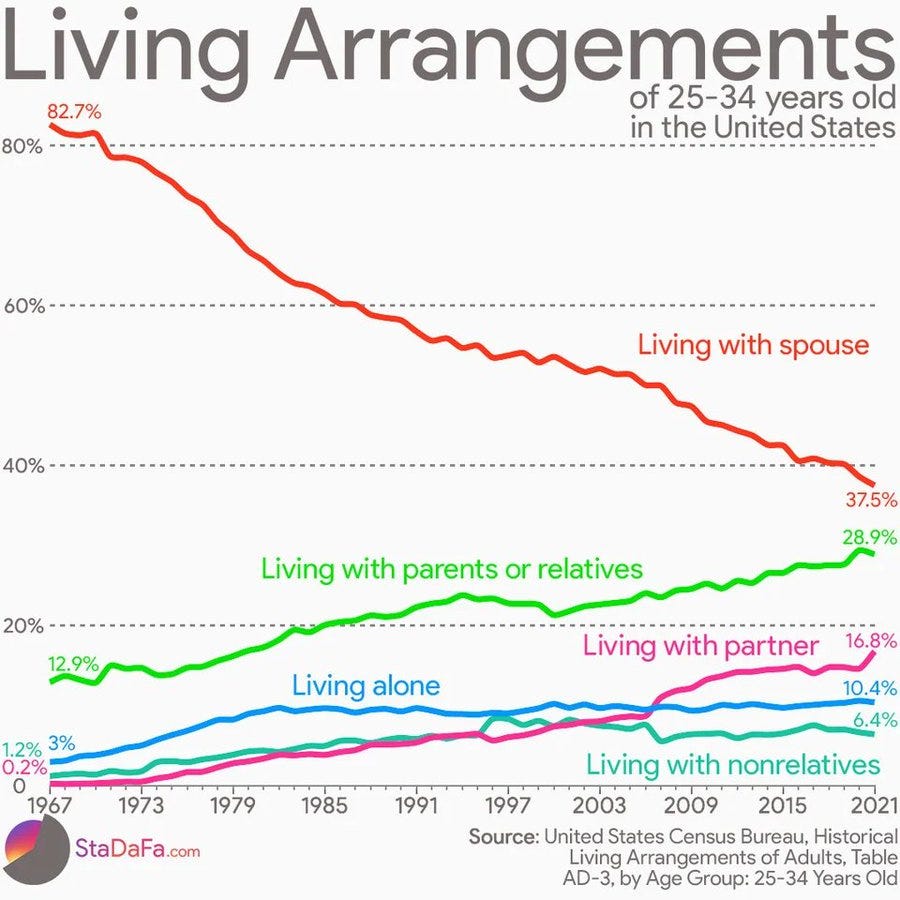

It is hard to avoid a sense of déjà vu when reading Unwin’s description of a civilization in decline. Exactly as happened in previous civilizations, female emancipation (“first wave feminism”) led directly to the abolition of absolute monogamy (“second wave feminism”) in the 1960s/70s across the Western world. Pre-nuptial chastity has shifted from the norm to something found almost exclusively in fringe religious groups.

Not only were “the same changes made” as in Unwin’s studied civilizations, but the “same sentiments [were] expressed.” Hammurabi needing to legislate against a husband being enslaved to pay off debts his wife accrued before marriage sounds like it could have come from a Manosphere blog post complaining about needing to pay prospective wives’ college debt. In the Roman Empire, “marriage became unfashionable, especially among the men—but perhaps it would be more just to say that marriage on these terms was despised, for there seemed to be few advantages to be gained, many to be lost.” Incels and MGTOWs today express precisely the same sentiments, for the same reasons, as Roman men two thousand years prior.

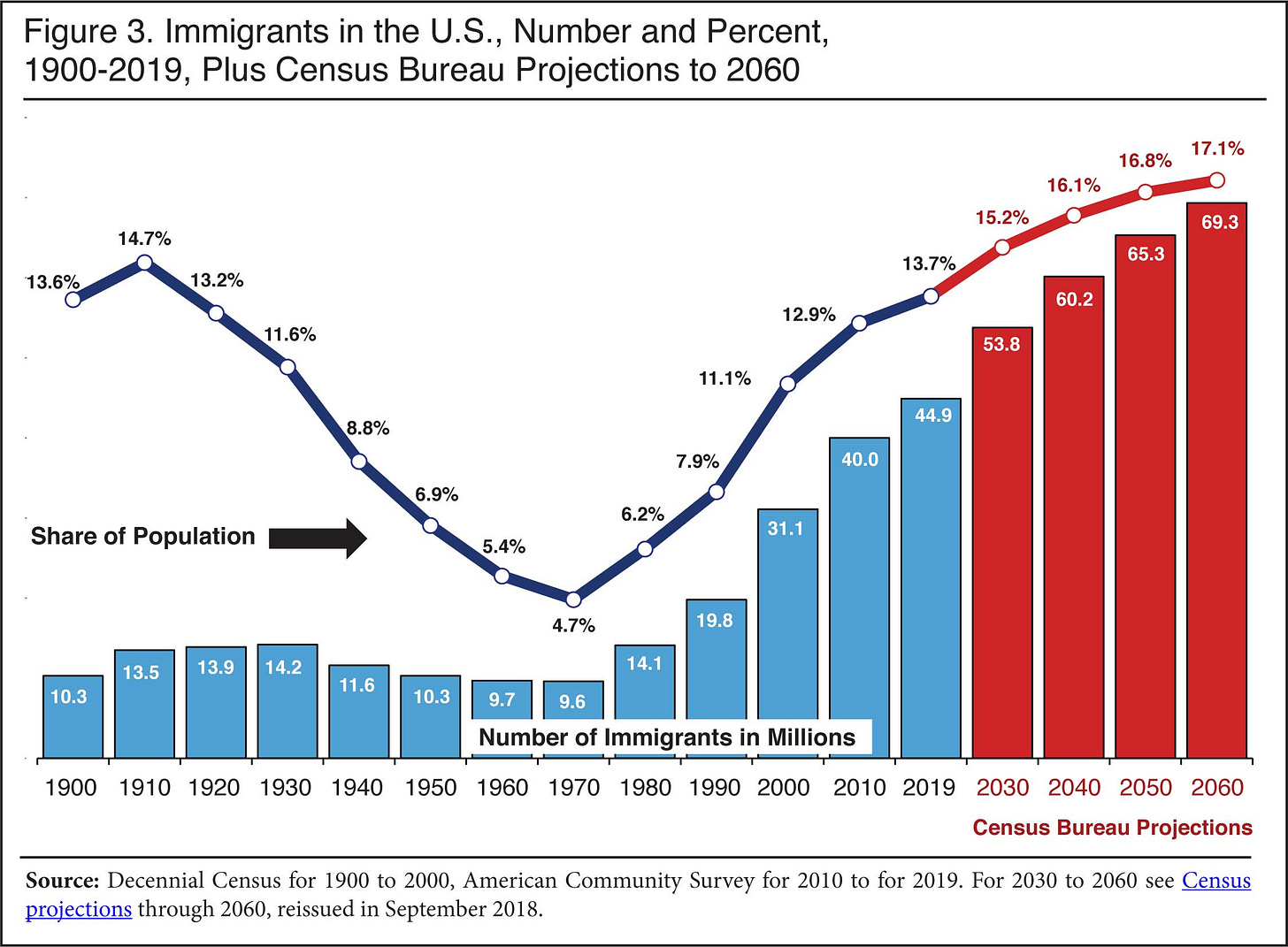

It would be a mistake to assume the Sexual Revolution was confined to the West. Something similar happened in most of the Third World around the 1990s, although the process is uneven.

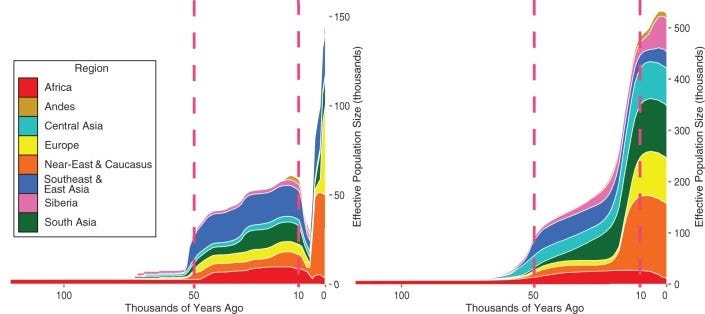

Unwin’s model predicts that “that as soon as the sexual opportunity of the society, or of a group within the society, [is] extended, the energy of the society, or of the group within it, decreases and finally disappears,” with full disappearance taking three generations (so the full effects of the Sexual Revolution will not be seen until ~2060 or so). Has social energy been decreasing since the Sexual Revolution? Yes. To begin with economic productivity, the Great Stagnation began around ~1973, the same time as the Sexual Revolution. Productivity growth across the First World has been decreasing since then, approaching zero in much of Western Europe. Science has likewise been slowing down since the mid-20th century, a slowdown which has occurred in many different fields, and thus is probably not the result of exhausting low-hanging fruit. Rationality itself has quantifiably declined.

Even popular culture is stuck.

The Henry Adams curve in energy consumption, perhaps the most quantifiable measure of the sophistication of a civilization, broke down in 1973. It could survive both World Wars and the Great Depression, but not the 1960s. As Unwin would have predicted, the groups that still exhibit some level of social energy in the West are overwhelmingly those in which the Sexual Revolution did not go as far, such as the upper-middle class, or those in which it occurred later, such as Asian immigrants and Mormons. Many other examples of this West-wide break in the early 1970s can be found at WTF Happened in 1971.

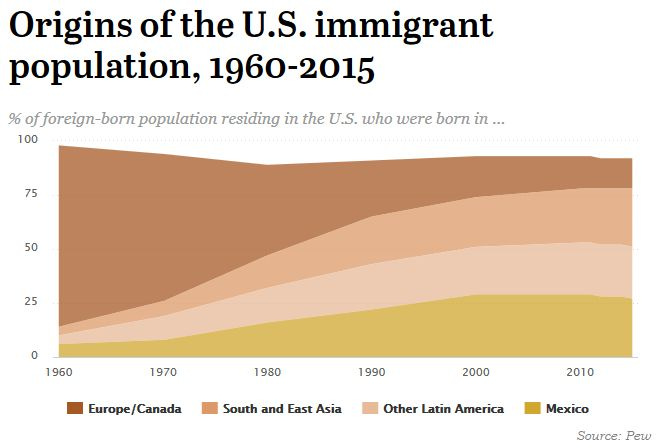

As with productive energy, so with expansive. It is hard to imagine a more impressive instance of expansive energy then the manned space program, which peaked with the Apollo Program in 19722. The last major Western outposts in Africa collapsed around this time, and instead of the West expanding into the rest of the world, the reverse began in earnest via mass immigration.

But this burst of Third World expansive energy is slowing down in those places which experienced a Sexual Revolution, particularly Mexico and East Asia. Increasingly, there aren’t enough young people to both emigrate and maintain the homeland, even if there’s an open door to the West.

The past 60 years thus match Unwin’s model closely, in both Western and world civilization. This should increase our confidence in its applicability to the future.

Unwin’s Explanation

Unwin explains his findings by concluding that the psychologists are correct: social energy is sublimated sexual energy, produced by restrictions on sexual opportunity, thus the perfect correlation between said restrictions and social energy, both within and between societies. An inability to satisfy sexual desires causes people to display this frustrated energy as social energy. This explanation is built on a foundation of then-current Freudian psychoanalysis, and Unwin repeatedly and approvingly cites Freud to that effect.

Nearly a century later, with the discrediting of Freudian psychology, this explanation seems wanting. It’s not at all obvious why, if it is the lack of sexual opportunity that produces social energy, the effect of compulsory celibacy upon cultural condition is “devastating,” or why women’s status is more important than that of men. Unwin believes that this is because children’s early upbringing is the responsibility of women, and thus a cohort’s character is more strongly formed by their mothers than their fathers. But he offers no causal explanation for how the frustrated sexual energy of a mother would be transmitted to her sons by any method of early upbringing, only positing that sexually continent mothers lavish more attention on their sons (how this leads to their sons displaying social energy is never detailed, and given the many null results of upbringing on adult behavior discovered by behavioral genetics3, a link seems unlikely). Furthermore, he finds that sexual restrictions on men have no effect unless restrictions on women are maximized, which does not fit with the psychological explanation of increased sexual repression leading to increased energy, as even if the effects of male restrictions on social energy are smaller, they should still exist at every level of continence, rather than exclusively differentiating absolute monogamy and polygamy.

Unwin does not like his finding that women’s emancipation inevitably leads to cultural decline and explains it as a result of “the extension of sexual opportunity which has always accompanied [the emancipation of women]” rather than the emancipation itself, writing that a society that wishes to maintain a high level of culture indefinitely must find a way to emancipate women without compromising on the institution of absolute monogamy. Despite his adherence to an inductive historical method for all other questions, Unwin’s inability to find a single society that accomplished this feat does not impinge upon his confidence that it can be done.

An Alternative Explanation: To Plant Trees for One’s Grandsons

Civilization, as a process, is indistinguishable from diminishing time-preference – Nick Land

The beginnings of an alternative explanation for Unwin’s findings come from the observation that what Unwin refers to as “human energy” can be, with almost no loss of accuracy, refined to “manly energy.” Conquest, colonization, far flung commerce, rational inquiry, self-reflection, technological progress, scientific advancement, and all of the other results of human energy are 95%+ male endeavors4. Women contribute little or nothing to them, except as wives and mothers. Furthermore, all of these things require low time preference, that is, the sacrifice of immediate gratification for the sake of the future. More impressive results typically require more sacrifice, particularly with regards to productive energy. But there is an intrinsic limit on delayed gratification: one’s lifespan. Since it is difficult to get full gratification out of personal enjoyment in old age (due to physical and mental ailments) and it takes time to develop the skills, connections, and experience to accomplish things (until young adulthood or longer), there are hard limits on delayed gratification for oneself. There are no such limits on sacrifice for posterity. Men will forge empires, build monuments, work long hours, and sacrifice their lives for their descendants.

But there’s a problem. Unlike mothers, it is difficult for fathers to be certain of their offspring. We did not evolve with paternity tests, and they were absent from nearly all of history. Our evolved instincts and behavior are as though they did not exist. Without paternal certainty, men have no reason to look to future generations. And how is paternal certainty to be attained without paternity tests? By restricting female sexuality. The more this is restricted, the more certain a man can be that his children are his, the more he can look to the future. This explains the perfect correspondence between cultural level and sexual restrictions below the level of absolute polygamy and monogamy, which is really a perfect correspondence between female sexual restrictions and cultural level, since restrictions on men do not matter unless restrictions on women have already been maximized. The key difference between modified and absolute polygamy/monogamy is that under the former, part or all of a man’s family and property can be taken from him at any time, thus understandably limiting men’s investment in the same way that insecure property rights lead to less capital investment.

What then, explains the difference between absolute monogamy and polygamy? This gap is arguably larger than that between any other adjacent levels of sexual restrictions, given that (with the partial exception of the Moors) rationalistic societies are exclusively absolutely monogamous, and there is no difference in paternal certainty. The answer lies in cooperation. In a polygamous society, a large segment of the men will never marry or have children, and thus have no stake in the future. To attain these, these men have two options: conquer wives from an adjacent society or destroy their own. In the absence of conquest, there is constant competition between men for wives, and men are thus forced to focus on competing with each other rather than working together to accomplish things, and so cannot display productive social energy. It is hard to maintain asabiyyah when half your fellow men would gladly kill you to take your wife. When surrounding peoples are weak, wives can be conquered from them instead, thus providing relief from intra-societal competition for wives. This temporary, post-conquest respite allowed the Moors to briefly reach the rationalistic state, but can never last without continual conquest. Absolute monogamy provides relief from constant intrasexual competition, letting men in these societies cooperate in service of other things5.

Another Hypothesis: What is Incentivized? What is Selected For?

The different modes of regulating sex relations incentivize different behaviors in men. Both sex and a family are powerful motivators for men, and access to each is different under different regimes. Under absolute monogamy, sex is conditional on marriage, which in turn is usually conditional on impressing a woman’s father, typically economically. This incentivizes productive, pro-social behavior. Under this regime, married fathers are respected as the foundation of society and through their own efforts can usually secure a stable family. Under modified monogamy, in which marriage can be terminated by either party at their discretion, a man’s family is dependent on his wife’s whims, and he must spend time and energy placating her rather than on greater accomplishment. Without prenuptial chastity, access to sex is dependent on impressing a woman, rather than her father, which incentivizes men to try to be attractive to women. And what attracts women? The topic is too involved to cover here6, but suffice to say it is not productive, pro-social behavior. When working hard to develop skills and work a stable, high skilled, or dangerous job does not particularly help men in acquiring a family or sex, men drop out, working only enough to get by, and in some cases try to achieve these things in other, less pro-social, ways. You get more of what you incentivize.

With enough generations, behavior that was once modified via incentives and slowly changing culture is encoded into the genes. Absolutely monogamous societies where sexual success primarily depends on economic status select for, among other things, conscientiousness, low time preference, and intelligence. Absolutely polygamous societies select for defecting on other men to get more women for yourself. And societies where women exhibit a high degree of sexual choice select for attractiveness to women, a suite of traits which includes, among other things, muscularity, impulsivity, propensity for interpersonal violence, and sociopathy. Furthermore, more selection for success in intrasexual competition (as is bound to happen with looser sex relations) inevitably means less selection for success in other things. Since there is no particular reason to believe that human energy (the power of reason, the power of creation, and the power of reflecting upon oneself) is helpful in intrasexual competition, and quite a bit of reason to believe the reverse, it follows that a group of people selected for many generations to excel at outcompeting each other for the favor of the opposite sex will be less capable of exhibiting it then one not so selected.

There is even some speculative evidence that this applies to other primates; monogamy being associated with larger brain size across species. On a generational timescale, sex relations can thus affect a group’s genetic propensity for exhibiting social energy.

An Alternative Interpretation: The Effects of Female Emancipation

The finding that female emancipation inevitably leads to the relaxation of absolute monogamy and cultural decline begs the question: is this causal? Unwin thinks not and believes that great cultural energy and female emancipation can be combined if absolute monogamy is retained, and thinks these are compatible. But the strength of this pattern cries out for an explanation, and there is reason to believe female emancipation causes these things, and furthermore causes each one independently, rather than solely causing decline via weakening sexual mores.

There are at least two ways by which female emancipation directly leads to cultural decline. First, female emancipation leads to greater female cultural influence, and women are, on average, more conformist, less logical, and less inclined to view arguments on the basis of their merits (rather than the personal qualities of the arguer) then men7. Second, women are much less inclined to consider the effects of changes on society then men are, rather than simply following their instincts. Historically, if society broke down, it was conquered, and the men were often killed or enslaved and did not leave descendants, while the women typically did.

Men thus have a genetically encoded tendency to try to make society work, even at some cost to themselves, that women lack.

As such, increased female influence over important institutions of any sort tends to lead to their decline8.

Women’s empowerment also causes the decline of absolute monogamy. Absolute monogamy requires that both men and women restrain their instincts9, but men are collectively more capable of doing so for the aforementioned evolutionary reason, while women have no such check. The inevitable modification of absolute monogamy via no-fault divorce results from women wanting to exercise their option to always trade up rather than commit for life10. In particular, modified monogamy allows women to continue receiving male investment without having to provide commitment11. The average woman also benefits much more from a freer sexual marketplace in her youth then a man does in his, since the average man finds the average young woman sexually attractive, but the reverse is not the case. For most young women, freer sex relations mean immense attention and power; for most young men it means loneliness and frustration. This is how women’s emancipation leads to a breakdown of pre-nuptial chastity. It is thus not surprising that every historical instance of absolute monogamy was established as a conspiracy among men to divide up women among themselves, imposed upon women against their will.

Verdict

Sex and Culture is a work of breathtaking ambition. It aims to create an entire anthropological framework for classifying societies, then analyze and explain the universal cause of cultural achievement and decline throughout all of human history. And Unwin comes close! His empirical observations are sound, and he has identified a common factor underlying all displays of social energy, one that surpasses all others in importance. His interpretation of his own findings is dated and flawed, but this does not detract from his model or his empirical discoveries.

The biggest blind spot in the work is Unwin’s lack of appreciation for race and genetics as factors in human cultural achievement. His belief is that the lower mental energy of primitive peoples results from sexual incontinence, rather than any genetic differences, and that, given identical sex relations, different racial stocks will display similar energy. His survey is strong evidence that sex relations determine the cultural category of a society as well as its course (towards displaying more or less social energy), but not of the absolute level of displayed energy, and there is abundant evidence that highly heritable qualities not altered in the short term by changes in sex relations such as intelligence play a large role in a culture’s achievement. An absolutely monogamous, deistic culture with average IQ of 100 is likely to achieve far more than one with an average IQ of 90. Nor does he consider the possibility that racial differences may predispose different groups to different degrees of sexual continence12. But this is only a minor part of the book and does not alter its core conclusions.

Another weakness of the book is stylistic. Many of Unwin’s definitions and concepts are repeated multiple times throughout the book, and he is very verbose. This, combined with the fact that his studies of uncivilized cultures tend to blur together for one not interested in them, makes the middle of the book a slog. Sex and Culture could use an updated edition with the repetition stripped out and the language modernized. This would also provide an opportunity to expand the book’s analysis to more civilizations. I would be fascinated to see how well Unwin’s model applies to cases such as the rise and fall of Russia, Spain’s Golden Age, Portugal’s Age of Discovery, France (particularly the Enlightenment and 19th century malaise), the Turkic conquests of most of the Muslim world (particularly the Ottomans and the Seljuks), Renaissance Italy, the Chinese dynastic cycle (particularly the Qing), the Dutch Golden Age, and the Mughals. Sufficient evidence probably exists to analyze all of these cases, but I don’t believe it has been collated anywhere (although Unwin’s full notes were much more extensive than his final draft; there may be some evidence there). I predict they would match Unwin’s views quite well, but they might falsify them too; either result would be valuable.

Among those interested in its subject matter, who should read this book? Anyone interested in uncivilized cultures, or who wants a broader overview of Unwin’s evidence and caveats. So should those interested in Unwin’s model, but not convinced, and those who want to critique it. Avid readers who are strongly concerned with the topic should read it too; my summary is comprehensive, but nowhere near as detailed as the full text. Who should not read this book? Those who are fully convinced by this review, who dislike reading long texts, or who could not be convinced by any amount of evidence should not waste their time reading an 800-page tome.

Implications for the Future

Unwin refuses to claim that social energy or human entropy or the Direction of the Cultural Process are good, but I have no such compunction. Human flourishing, the exercise of reason, creation, and self-reflection, the expansion to new frontiers (space, perhaps?), science, understanding of the natural world, technology—all of these are good, and should be pursued. The disappearance of rational thought and civilizational decline to a lower, inert level are bad, and should be avoided.

The good news is that our many problems—among others, fertility collapse, fiscal cliffs, institutional sclerosis, regulatory bloat, declining productivity, dysgenics, demographic replacement, and the slow death of science—have but one neck, which can be cut by getting one thing right: reestablish absolute monogamy13. Want innovation? To go to space? High GDP? Your own country? High art and architecture? Great literature? Impressive philosophy? To unravel the secrets of the universe? Reestablish absolute monogamy. Nothing else matters long term. The evidence of history suggests this can only be accomplished by deemancipating women, which must be done first1415.

The bad news is that we’re on a trajectory of decline, and it probably can’t be stopped. A number of Unwin’s civilized societies saw their decline happening and took halting steps to reverse it but were never able to reimpose absolute monogamy before being conquered by a more energetic people and thus failed. Furthermore, stability is a myth. Every one of Unwin’s rationalistic cultures failed in the same way, for the same reasons, suggesting a kind of inevitability16. We can shine brightly, but not forever. But there is a note of hope. Two of Unwin’s cultures, the Sumerians and the Anglo-Saxons, successfully reimposed absolute monogamy after being conquered. The Sumerians had a centuries-long renaissance, and the English, overwhelmingly descended from the Anglo-Saxons, built history’s greatest empire on top of most of the modern world. Decline may have been inevitable, but we can rise again.

Further Reading

– A list of particularly important excerpts from Sex and Culture.

https://www.kirkdurston.com/blog/unwin - Another review of Sex and Culture.

Dalrock's Blog – An excellent blog with extensive writing on the importance of (absolutely monogamous) marriage to society, men’s motivations, and the Sexual Revolution and its consequences. Some highly relevant posts: Forfeiting the Patriarchal Dividend, Why Game is a Threat to Our Values, The Weakened Signal Hits Home, The Mysterious Male Marriage Premium, In Search of the Peter Pan Manboy, Commitment Issues, Why Isn't Carl Good Enough?, How the Destruction of Marriage is Strangling the Feminist Welfare State, The Child Support Catastrophe, and The Economics of Divorce Theft and Exploitation. There are many more relevant posts on the blog, which I cannot recommend highly enough.

https://westhunt.wordpress.com/2015/05/26/when-public-policy-meets-elementary-biology/ - A blog post from Gregory Cochran with a proposal for stabilizing families.

https://archive.org/details/b20442580/page/n7/mode/2up - A downloadable, PDF version of Sex and Culture, for the interested reader.

https://bioleninism.wordpress.com/2013/02/12/the-sociology-of-dysgenia/ - A blog post from Spandrell explaining the link between non-absolute monogamy/polygamy and dysgenics. Other relevant Spandrell posts are found here.

https://gwern.net/doc/sociology/2012-henrich.pdf - A paper explaining some of the advantages of monogamy over polygamy, and arguing that is is a group-selected cultural trait.

https://twitter.com/BirthGauge/with_replies - A Twitter account dedicated to tracking world fertility rates.

Footnotes

Quotes in this section are from this article: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/1999/12/13/national/century-of-change-marriage-sheds-its-traditional-shackles/. Quotes elsewhere are from Sex and Culture unless otherwise noted. For more reading on the Meiji Civil Code, see here or the full text of the code itself.

It is possible that manned spaceflight could surpass Apollo in the near future, but the main drivers of current progress in spaceflight are Elon Musk, who was born when South Africa was still absolutely monogamous, and China, whose sexual revolution didn’t fully get going until urbanization. In both cases, the involved societies went through a similar process as the West, only delayed a generation or so. Unwin’s thesis would predict that current rapid progress in spaceflight will drop off again within ~10 years or so, but won’t necessarily completely stop until three generations after these changes (~2090 or so).

See Robert Plomin’s Blueprint for an overview of these findings.

This should be obvious, but Charles Murray’s Human Accomplishment quantifies it more rigorously.

Indeed, there is good evidence that monogamy is group-selected cultural practice.

But I refer interested readers to 50 Shades of Grey or other romance novels for an idea. For a more concrete analysis, The Rational Male, Chateau Heartiste (warning: language) and other PUA blogs break down their interpretation of what women are sexually attracted to based on many, many trials and errors.

For more on cultural feminization, see Cultural Feminization: An Introduction, The Law Empinkened, The Great Feminization, Fair Sex, Women's Tears Win in the Marketplace of Ideas, and Sex and the Academy.

The Progressive mainstream has noticed this phenomenon, although in typical Progressive fashion, they invert cause and effect.

Men’s instincts tend towards polygamy, having sex with many women at the same time, ideally with exclusive sexual access and always retaining the option to branch out further. Women’s instincts tend towards hypergamy, having sex with the most attractive man, ideally while receiving investment (not necessarily from the same man) and always retaining the option to trade up.

In the long run, modified monogamy leads to lower male investment, a fact much lamented by social conservatives who wonder why men today aren’t manning up like their grandfathers did. This is one instance of the general trend of men investing less in the future when absolute monogamy is lost.

Obviously, race does not deterministically cause sex relations, but there is considerable evidence, such as the alacrity with which African-Americans abandoned marriage, pre-nuptial chastity, and monogamy (in comparison to white Americans), that different racial groups tend towards different regulations.

The one class of exceptions are genuinely novel problems involving nonhuman agents, that is, AI.

The deemancipation of women should thus be an Effective Altruist cause area.

Unwin doesn’t believe this is necessary, but his own inductive historical method suggests it is. If we are to take any of his conclusions seriously, we are forced to adopt this position.

Unwin believes there is no reason why human energy can’t be maintained indefinitely, but once again, his own method suggests otherwise.

I am reading “The End of Woman” by Carrie Gress and she mentions this 1934 book. She says of the findings, “the greater a culture’s sexual restraint, the greater that culture’s accomplishments... but “as soon as a culture abandoned monogamy... it collapsed within three generations.” If this English ethnologist from Oxford is correct, I say the US is not looking so good for longevity.

Well-written and on the mark.