If you want to join Britain’s thriving cocaine smuggling industry, you have to be Albanian1.

There’s no a priori reason for this to be the case. Albanians do not have a racial, cultural, geographic, or political affinity for Colombian narcotics. A reasonable and informed observer in 2000 would not have predicted they would come to dominate the industry. But they would have been able to predict that some ethnic minority would, because organized crime groups are almost always organized along ethnic lines. This is true even where the relevant ethnic group is less criminal on average than society at large, such as the Jewish mafia in early 20th century America.

This phenomenon isn’t limited to criminal enterprises. Chaldeans control 90% of the grocery stores in Detroit. 40% of the truck drivers in California are Sikh, and about a third (~150,000/500,000) of US Sikhs are truck drivers. About 95% of the Dunkin’ Donuts stores in Chicago and the Midwest are owned by Indians, mostly Gujarati Patels. In New England and New York, 60% of Dunkin’ Donuts are operated by Portuguese immigrants. 90% of the liquor stores in Baltimore are owned by Koreans. I am not the first, the tenth, or the hundredth person to notice this. From the 1999 New York Times article, A Patel Motel Cartel?:

America's motels constitute what could be called a nonlinear ethnic niche: a certain ethnic group becomes entrenched in a clearly identifiable economic sector, working at jobs for which it has no evident cultural, geographical or even racial affinity.

I don't mean Italians owning pizzerias, or Japanese people running judo schools. I mean, to use an obvious example, the Korean dominance of the deli-and-grocery sector in New York -- a city where the Chinese run most laundries and Sri Lankans, in case you didn't know this, run most porn-video stores. Or the Arabs in greater Detroit, who have a stranglehold on gas stations, or the Vietnamese who monopolize nail salons in Los Angeles. Farther afield, I could mention London's taxi drivers, sharp-tongued in their big black cars, many of whom are Jews from the city's East End; or the security guards outside New Delhi's more affluent residences, virtually all of whom are Nepalese; or the prostitutes in the United Arab Emirates, who are so often women from Russia.

But I don’t believe previous writers have really considered the broader implications. The general economic case2 for immigration is that immigration means larger markets and thence more competition, more opportunities for specialization, more economies of scale, and so on. I’ve covered in the past how ubiquitous international trade means this doesn’t apply today (small nations can benefit from the competition, specialization, and scale of the world at large3), but the existence of nonlinear ethnic niches weakens this case even further. The key point is that immigration fractures national markets. Once a niche is taken over, outsiders can no longer compete within it.

There is still competition within ethnic groups in these niches, but these groups are tiny fractions of the population and often have informal institutions and kinship structures to coordinate as cartels. For example, in the words of Vishal Shah, a Dunkin’ Donuts owner in Chicago:

“In Indian culture, if it’s a friend of your father you still call him uncle,” Shah said. “You are family through respect because your parents are friends; everybody’s family.

That makes a big difference on a daily basis in business. “We all help each other,” said Shah, whose family has six stores. “Whenever someone needs something no one ever said I don’t have the time. If your mixer goes down, it’s a matter of a couple of phone calls and you know you’re taken care of.” Likewise, he said, if half his crew gets sick, those same few calls will get him back in business.

What this means is that in vocations taken over by nonlinear ethnic niches, modern-day multiethnic Chicago has a smaller talent pool to draw from than the smaller, but more homogenous4 Chicago of generations past, and mutatis mutandis for many American cities.

We can roughly quantify the importance of nonlinear ethnic niches by looking at levels of co-ethnic hiring in new firms.

But this will significantly underestimate co-ethnic hiring in cases where the sending countries are themselves strongly multiethnic. The correct unit of analysis for the motel industry, for example, is not “Indians,” but Gujaratis. For Detroit groceries, it’s the miniscule Chaldean minority, not “Iraqis.” And while this tells you approximately how dependent a given country’s immigrants are on these niches, it does not tell you how dominant they are within them, which is the more important number5.

It’s worth looking at some of the more famous nonlinear ethnic niches in the US to get an idea of how they operate.

Cambodian Donut Shops

Cambodians run about 80% of the donut shops in Southern California (Cambodians are 0.17% of the population of California). The Cambodian donut empire got its start with refugee Ted Ngoy, who first learned the trade thanks to an affirmative action program to increase minority hiring at Winchell’s Donuts. The Cambodians were able to totally dominate this traditional American culinary sector through a mix of extended family credit and the use of tong tines, an informal lending club. From Curtis 2016, page 112:

The Cambodian variation of the arrangement allowed refugees to swiftly receive and pay back money. The loans were tax-free and interest-free, supporting Kolker's assertion that informal lending clubs exist “to save money, not to make it.” Perhaps most importantly, they made cash “quickly available to those who couldn't otherwise get credit.” As Sokhom notes, tong tines were common for “Cambodians who cannot get a bank loan or did not know how.” Being able to, in Lonh’s words, “kind of avoid the bank” through personal savings, the help of friends and family, or the support of a tong tine allowed Cambodians swifter access to independent business ownership with lower initial expenditures, fewer long-term costs, and less engagement with U.S. financial institutions.

This ability to borrow money cheaply made financing much easier for them than for their American competitors. Once the business was purchased, Cambodians could also keep operating costs down through informal employment of family labor, allowing them to get around expensive income taxes, not to mention labor laws and regulations (including ones around child labor) (Curtis 2016, page 115).

Notably, Cambodian donut shop owners are notoriously conservative and invest and innovate very little (Curtis 2016, page 117). With access to cheaper labor and financing than their American competitors they have little incentive to create true productivity improvements, and the Cambodian community of Southern California is too small (65,000 people) and lacks the “culture of improvement” required to generate these innovations internally. From a consumer perspective, this is OK in the short run (efficiency improvements from cheaper labor and financing get passed on in lower prices), but bad in the long run (because labor and money can only get so cheap, and cheaper does not mean different or better; there’s a hard limit on how much donut shops can improve without innovation6). This is analogous to Britain’s infamous 21st century de-automation of car washes in favor of immigrant labor.

Patel Motels

Gujaratis, mostly with the surname Patel, run an estimated 42% of the hotels and motels in the United States (Gujaratis are about 0.3% of the US population, and this number was much lower back in 1999 when this phenomenon was first noticed). This rises to 80-90% of motels in small town America. The Patel motel cartel got its start with an illegal immigrant, Kanjibhai Desai, in the 1940s. The initial attraction to Patels was that motel ownership did not require English proficiency, and as with the Cambodians Patel motel owners were able to use informal ethnic loan networks and immigrant family labor brought in via family reunification from India to undercut their American competitors. Patels now totally dominate the hospitality industry in the US outside of the big chains.

Vietnamese Nail Salons

Over half the nail salons in the United States are run by Vietnamese, which rises to more than 80% in California (Vietnamese are 0.7% of the US population). Just like the Patels and the Cambodians, Vietnamese immigrants were able to finance nail salons more easily than American competitors because they had access to below-market credit from family and friends.

Pro-immigration conservatives often celebrate the small business ownership characteristic of nonlinear ethnic niches as a route to assimilation, but that’s backwards. As with the Patels, Vietnamese refugees were attracted to nail salons because they didn’t require English proficiency and in fact enabled ethnic separation from America7:

Vietnamese refugee women are likely to become manicurists because the salon business provides a high degree of autonomy and insulation from an alien—American—culture, language and people.

After the ethnic network was established, Vietnamese owners gained another advantage over non-Vietnamese competitors: better access to workers and training. The language barrier is part of this; once most salon owners spoke primarily Vietnamese, prospective workers had to too, and vice-versa, and cosmetology schools began teaching courses in Vietnamese rather than English. Vietnamese owners and workers could also use the same ethnic and kinship networks used for financing to find each other, avoiding the difficult, annoying, and ineffective impersonal hiring process. This plainly goes against the spirit of Civil Rights law in the US, but it’s impossible to apply these laws to informal networks the way they can be to formal institutions, nor has anyone really tried.

Mechanics

As Thomas Sowell would say, prejudice is free, but discrimination has costs. In a market economy, not hiring or working with disfavored groups means leaving money on the table and being outcompeted by less scrupulous entrepreneurs8. Extra-market forces, such as fear of the EEOC driving private diversity efforts and monopolies without fear of competition can change this, but that’s not what’s going on here. There is no society-wide push to fill the motel sector with Patels or ensure every nail salon is Vietnamese, and the small businesses they dominate are not monopolies. So how do these nonlinear ethnic niches work?

The common themes in all of these ethnic niches are:

They are founded and sustained by first-generation immigrants.

This allows niche owners to exploit labor arbitrage through their kinship and social networks in their home countries, and also creates a language barrier that makes it harder to find workers or partners outside the ethnic group and harder for ethnic workers to find work outside the niche. Running a low-prestige small business on tight margins is not easy work, and second-generation and beyond ethnics often leave.

They are in low-prestige, low-margin sectors that nevertheless used to be major avenues of upwards mobility for Americans and in which there is no technical reason for this ethnic group to dominate9 (unlike e.g. Chinese dominance of Chinese restaurants). Note that this is distinct from an ethnic group becoming prominent in an industry because of their traits being unusually well-suited to it.

The fact that these sectors are small and don’t have much prestige is what allows them to be dominated. The main reason people run motels, small grocery stores, gas stations, nail salons, and donut shops is money, not prestige, status, or any other intangible (this comes across very strongly in the history of the Cambodian donut niche I’ve been relying on; several owners express contempt for the industry on pages 120-123 but say it’s good money), and this means once undercut through the tactics below, non-ethnics stop trying to enter. Combined with the small size of these sectors (about 300 Dunkin’ Donuts in the Chicago area, for example), and the advantages given below can quickly snowball into complete dominance, at which point maintaining the niche is much easier than creating it.

These ethnic networks attain dominance through a combination of below-market-rate extended family loans, exploiting labor arbitrage between the US and countries of origin, labor networking within the group, and racial privileges.

The most important reason these nonlinear ethnic niches can dominate business ownership of some segments of the economy is below-market-rate loans. Small businesses tend to have tiny profit margins, and getting better terms on financing is a huge advantage. Every single history or explainer of a nonlinear ethnic niche mentions how important credit from extended families and informal ethnic networks are. Americans do not typically have this ability; we don’t have ethnic networks and our family structures are tiny relative to most of the world. Formal sources of credit, like banks or the Small Business Administration, are typically legally prohibited from favoring specific ethnic groups, except where they have mandates to favor nonwhites broadly. We are dependent on formal society treating us fairly as individuals.

A second advantage these networks have is wage arbitrage between the US and their countries of origin (Vietnam, India, Cambodia, Iraq, and so on). American immigration law favoring family reunification and hence chain migration enables this by allowing individual employers to take full advantage of this arbitrage (because it is socially very difficult for family members to just change jobs, especially since they usually don’t speak English well) outside the caps and requirements of labor visas like the H1-B. In the words of Padma Rangaswamy:

The dominance of South Asians in the Dunkin’ Donuts franchise industry in the American Midwest can be explained with reference to many of the classic theories of niche formation—the desire of immigrants for self-employment, contribution of family members, access to cheap labour and informal funding, and group solidarity. But its unique trajectory of rapid growth and success owes as much to the selective nature of U.S. immigration policy. Its origins lie in the post-1965 immigration of skilled professionals who first bought into the business. It grew as a result of the legitimate use of the family reunification law which permitted the early immigrants to sponsor less-educated relatives and employ them in the business. However, the labour of unauthorized immigrants and continued chain migration of family members have contributed most significantly to the profitability of the businesses, and enabled South Asians to continue to dominate the field.

The same individuals are massively more productive in the United States than in Third World countries10. This means part of the difference in wages between what they would have earned at home and what they produce in the United States can be pocketed by the business owner, saving on labor costs. Furthermore, part of total compensation is getting to live in a First World country and having a path to citizenship (plus free public education for children), which is effectively a subsidy from the American nation to the employer, who doesn’t have to pay these costs11. This is not available to American small business owners, very few of whom have family in enormously poorer countries.

The last pathway by which nonlinear ethnic niches proliferate is the various racial privileges that exist in the United States12. The Cambodian donut shop empire began with affirmative action, and in addition to below-market credit from the ethnic network, nonwhite small businessmen can receive below-market loans from government programs designed to promote nonwhite business ownership and benefit from government contracts set aside solely for nonwhites. In fact, getting access to these racial privileges is what motivated the creation of the Asian-American US census category in 1980. Indian small businessmen lobbied the census bureau to group them with East Asians (at the time classified as Orientals) rather than whites to benefit from these programs. While it doesn’t explain the formation of niches (why concentrate in motels when these privileges apply so broadly13?), it does help these networks muscle out white competitors to begin with.

Once ethnic dominance is established, it’s much easier to sustain, because once the niche is captured co-ethnics have the enormous incumbent advantage of labor networking within the group. Employers finding good workers and workers finding employers is difficult, and so being able to focus that search on co-ethnics makes this matching process much easier. Even more importantly, there’s usually a language barrier between first-generation immigrants and Americans as a whole, which makes it hard for non co-ethnics to work in dominated niches, and hard for ethnic owners to defect from the cartel. This is psychologically self-reinforcing; the more dominant a group is within its niche, the less likely outsiders are to imagine themselves entering it and the more likely insiders are to imagine themselves staying within it.

Winners and Losers

The big winners of these nonlinear ethnic niches are the businessmen themselves, who are broadly protected from competition outside of their small group, and secondarily non-businessmen members of these ethnic groups, who have these protected employers to fall back on if needed, as well as a protected source of visas into the United States. In the short run, consumers benefit, because the lower costs from cheaper financing and labor get passed on. In the long run, however, consumers are harmed because the fact that these niches are so effectively isolated from the broader American market and possess mechanisms for informal coordination lowers competitive pressure and hence innovation. Businessmen protected within their ethnic niche can rest on their laurels.

The big losers are Americans at large. Not only do ethnic niches facilitate mass immigration, with all the problems that causes, but small business ownership, especially franchises, is one of the classic paths of upwards mobility for Americans. As ethnic networks take over more and more small businesses in more and more areas, this gets closed off, leaving only14 the incredibly overcrowded pathway of college and a professional career for Americans looking to self-improve. The historic American love of economic independence through ownership, damaged but never destroyed by the massive economies of scale of the Industrial Revolution, is dying15.

Anti-Modernity

So nonlinear ethnic niches exist and are able to sustain themselves in the face of market competition. This might hurt some Americans, but so do a million other problems. Does it really matter?

Yes. Western civilization has been different for so long (more than 700 years) that we’ve forgotten what this looks like, but nonlinear ethnic niches are a throwback to premodern forms of social organization, with all that implies.

The Collective Brain

In The WEIRDest People in the World, Joseph Henrich argues that the “special sauce” of Western exceptionalism was free association and individualism. The usual pattern of human social organizations throughout history is kin-based. These kinship structures are almost invariably extended beyond immediate relatives through fictive kinship, but nevertheless have low upper limits on size and balkanize society at large into much smaller competing groups. By breaking extended kin-based structures into nuclear families, the Western European Marriage Pattern facilitated impersonal cooperation based on the task at hand rather than kinship instead, which both enabled cooperation at much larger scales and greatly improved the efficiency of learning:

Nevertheless, while large kin-groups beat nuclear families in size and interconnectedness by tying more people together, nuclear families have the potential to be part of even larger collective brains if they can build broad ranging relationships or join voluntary groups that connect them with a sprawling network of experts. Moreover, unconstrained by the bonds of kinship, learners can potentially select particularly knowledgeable or skilled teachers from this broader network. To see why this is important, consider the difference between learning a crop rotation strategy from the best person in your extended family (a paternal uncle, say) or the best person in your town (the rich farmer with the big house). Your uncle probably had access to the same agricultural know-how as your father, though perhaps he was more attentive than your father or incorporated a few insights of his own. By contrast, the most successful farmer in the community may very well have cultural know-how that your father’s family never acquired, and you may be able to combine insights from him with those from your own family to produce an even better set of routines or practices.

Once an ethnic group monopolizes an economic niche, this is no longer the case. Rather than being able to learn from the best in any area, prospective entrants can only learn from the best in their small ethnic minority. And the mechanisms by which these niches form and propagate to begin with encourage kinship networks within these small ethnic groups on top of that. From page 134 of Blue Dreams: Korean Americans and the Los Angeles riots:

The vast majority of Korean immigrants invest what money they have for their own businesses, above all, and for close kin and possibly friends. In this regard, the nature of chain migration and the significance of kinship are crucial for many immigrant entrepreneurs.

Large-scale cooperation and a bigger collective brain, and not individual exceptionalism16, is what allowed Western civilization to break out of the primordial grinding misery of the Malthusian trap, make real scientific, philosophical, cultural, political, moral, material, and technological progress, and so utterly dominate and transform the world for centuries. Nonlinear ethnic niches are slowly dragging Western society back into the default human world of tribes, clans, extended families, and middleman minorities we escaped 700 years ago.

Internal Markets

In most agrarian societies, commerce, tax farming, moneylending, and many skilled trades were the province of particular ethnic minorities, whether that be Greeks and Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe, Fujianese in Southeast Asia or any number of castes in different parts of India (see Chapter 1 of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century for more examples). By contrast, northwestern Europe was comparatively ethnically homogeneous, with middleman majorities. Homogeneity enabled Clarkian selection (that is, diffusion of productive traits via higher fertility of the rich and downwards mobility in a market economy). Genetic and familially-transmitted cultural adaptations do not diffuse from endogamous ethnic groups into the broader population. Market-dominant and middleman minorities are thus problematic for national development17. I believe lacking them was one of the biggest advantages of northwestern Europe in general and England in particular over Eastern Europe.

18th and 19th century nation-builders, from Bismarck to Alexander Hamilton to Pyotr Stolypin to Meiji Japan to Napoleon, were obsessed with creating national markets, the bigger and more homogenous the better. Breaking down internal barriers to trade allows for more competition and larger economies of scale, hence increasing national prosperity and national power. It also breaks down internal cultural divisions within the nation, allowing it to be more united in the face of outside threats. Most discourse on this focuses on political barriers, such as internal tariffs (which can be removed by legislation), or physical barriers, such as mountains (which can be removed through infrastructure), but cultural barriers (especially language) have the same effects. A common slogan in the online right is “a nation, not an economic zone,” but the reality is that these go hand-in-hand. The more internally homogenous the nation, the larger the effective market size, the more prosperous the people and the more powerful the state18.

This is well-known in development economics. From Yavuz 2021:

Next, we find that ethnic diversity is negatively associated with new business creation in developing countries. This provides support for our argument that lack of homogeneity in ethnically diverse societies results in the difficulties in forming social networks across different ethnic groups to access resources, and markets, and achieving greater outreach. While ethnic groups facilitate the diffusion of credit and ideas within their boundaries to fill the voids in formal institutions, and minimizes transaction costs (Ouchi, 1980), out-group members are discriminated against in the allocation of resources, which results in less entrepreneurial activity in more ethnically diverse societies.

Yet the lesson that diversity fractures national markets has yet to sink in. In the United States, this manifests in more diverse areas founding 26-28% (per standard deviation of diversity) fewer large firms, but 6-8% more (per standard deviation of diversity) small firms (Boudreaux 2020). These small firms are more amenable to nonlinear ethnic niches; a tong tine or SBA loan can fund a donut shop purchase, but not an auto factory, and preferentially hiring family members to take advantage of informal labor gives more of an edge in establishments with five workers than five thousand. Given the lack of competition within ethnic niches, we might expect small firms in more ethnically fractured areas to be less productive, and they are.

Nonlinear ethnic niches are what fracturing internal markets along cultural lines looks like in the real world; the undoing of centuries of progress purchased in blood by visionary statesmen.

Informality

One of the most notable things about nonlinear ethnic niches is the lack of formal organizations. There are a handful of formal institutions involved, such as VietAid for the Vietnamese nail salon owners and the Asian-American Hotel Owners Association19 for the motel Patels, but these are much less important than informal kinship and ethnic ties. In particular, ethnic money pooling schemes replace formal banks as a source of finance and family members replace paid formal employees as a source of labor.

Informal networks do have some advantages over formal institutions, like lower transaction costs within the network and dying more easily once they’ve served their purpose. But the benefits of formal institutions are legion. Formal institutions scale better, can maintain their purpose for longer, better align individuals with otherwise distinct interests towards a common purpose, and are more fair. At a societal level, legal succession works better than civil war, banks work better than tong tines, supermarkets work better than street vendors, and police forces work better than clan justice. From the state’s perspective, formal institutions are legible and can be taxed, regulated, or negotiated with.

Formal institutions are also critical for specialization; imagine trying to rely on your kinship network (and maybe some friends) alone to build a power plant, operate a grocery store, study physics, talk about fiction, and maintain public order. It’s not possible for one group to do all of those things well, but freely-associating individuals can create different companies for the power plant and store, a police force to maintain public order, a club for the fiction, and a university for the physics.

So it’s not too surprising to see that one of the markers of Western, and particularly Anglo, ascent before the Industrial Revolution was the explosion in formal clubs.

Formal institutions of freely-associating individuals with far higher ceiling capabilities replacing informal kinship networks is perhaps the core social trend of modernity.

Americans historically were exceptional at building formal institutions, with more corporations than the rest of the world combined in 1812, and freedom of association is so important to Americans it’s protected in the First Amendment (though since abrogated by the Civil Rights Act of 1964). Formal institutions are sometimes set against individual agency (consider the pain of interacting with the DMV or medical bureaucracies), but it very much depends on the context. If Americans in the 19th century needed a bridge, they created a temporary corporation to build it, and this bridge-building corporation was a specialized tool that did not rule the rest of social or economic life like a kinship-based organization would. For all of their (very well documented and much lamented) problems, formal institutions are by far the best way to combine collective action with individual agency.

As with shrinking the collective brain and fracturing national markets, nonlinear ethnic niches replacing formal institutions with informal kinship networks should be seen as a regression towards the (worse) human mean, turning back the clock on 700 years of Western progress.

India: the country of the future?

The extreme example of nonlinear ethnic niches is India20, where practically every economic niche is locked down by an endogamous caste, a system that is thousands of years old.

This has a bunch of bad effects, even aside from the long-term problems of shutting down Clarkian selection (because selection for success does not diffuse outside of the successful man’s caste) and entrenching kin-based structures over impersonal ones. For example, caste discrimination in employment, even in large, formal international firms where the caste system should be less relevant, is rampant.

This causes the same problems as affirmative action (which is also extremely widespread in Indian government positions). Companies hire worse workers and are less productive, consumers get worse and more expensive products, and of course competent out-caste individuals are personally hurt. We can ask Thomas Sowell’s question again: how does this sustain itself in the face of market competition without some sort of legal mandate?

The answer is that this behavior is economically rational even in the absence of prejudice. In a society like India, balkanized into ethnic niches, if you allow your niche to be taken over by a different ethnic group, you will then be discriminated against in turn, and unlike America, there’s no niche-less majority of the economy to fall back on. Hence individuals within companies have very strong incentives to discriminate, and even if we abstract away individual incentives (which we shouldn’t do), companies benefit from discriminating against all but the most capable group for their particular niche, since that niche will inevitably be dominated by a group rather than employ individuals.

Indian companies constantly complain of labor shortages [1][2][3][4][5][6], which is odd in a country of 1.5 billion people with almost 650 million near-zero productivity small farmers and graduate unemployment approaching 30%21. But it makes sense when you consider that the correct labor market is not “Indians,” or even “people within commuting distance,” but rather “people of the right jati,” a much smaller group (and even less likely than numbers and IQ would suggest to contain specialized skills of the desired sort if they’re not part of that caste’s traditional economic role22. This isn’t just because they’re likely to lack skills; about 40% of Indians are willing to forgo money equivalent to 10 days wages just to avoid doing non-caste-appropriate tasks for 10 minutes). Something similar occurs in capital markets, with caste members refusing to lend to non-caste members, leading to cases where entrepreneurs of the locally-dominant caste in a certain niche are far less capital efficient than their out-caste competitors, but never get outcompeted, causing persistent capital misallocation. See Munshi 2017 for an example of this in the Tirupur knitted garments industry and several other examples of caste fracturing markets and causing inefficiency.

Furthermore, a person can only know and meaningfully interact with so many people. Dunbar’s number (150) is dubious, but the true number is probably less than a thousand for all but the most socially-adept individuals. The number of people a person will be forced to interact (in classrooms, in the workplace) is nearly fixed, and doesn’t increase when the total population increases. If part of this circle is effectively off-limits as workers, employers, contractors, and so forth because they are not of the correct ethnicity, this reduces effective market size for any given worker or employer further23. What this means is that a small, but comparatively homogeneous (or composed of groups with low ingroup preference) area24, such as Reykjavik, can have de facto larger labor markets than a highly diverse place dominated by ethnic niches, such as New Delhi, and this is true even if individual castes within New Delhi are larger than the entire population of Iceland, because large chunks of the social circles of individual Delhiites will be composed of outgroup members off-limits for various activities25. Indian villages are so ethnically fractured that each caste makes up on average only 6% of the village’s population, and even with residential segregation this only increases to 14% of the ward.

In a way, India’s unique social structure keeps it a preindustrial economy even with modern technology, with cottage industries dominating factories.

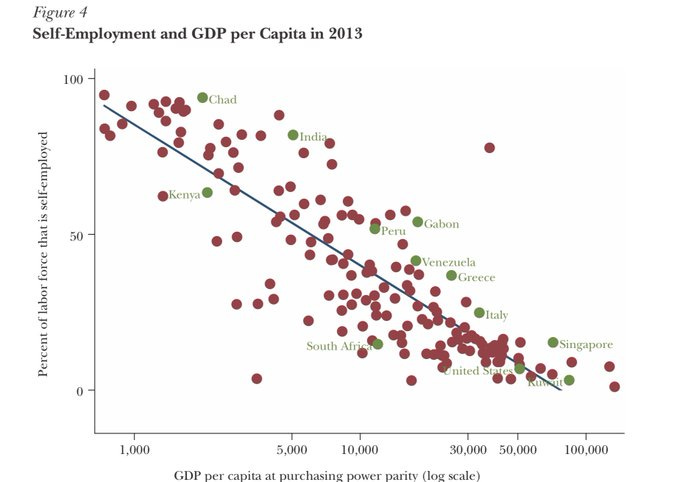

Indian firms are notoriously terrible at scaling, which is particularly bad in manufacturing, a sector that greatly benefits from learning curves and other economies of scale. Unlike American firms, which grow and expand if they succeed and survive, or even Mexican firms, surviving Indian firms do not expand at all on average, leading to a proliferation of tiny, low-productivity firms.

India shows that there is no upper limit to the prevalence of nonlinear ethnic niches. If there are enough separate ethnicities with the correct social structures (kin-based) to support them, they can take over the entire economy, spreading their pathologies to sectors more important than Dunkin’ Donuts.

Conclusions

Immigration is the most reactionary force in Western societies today. Anti-woke liberals idealize the 1990s, intellectually honest social conservatives prefer the 1950s, Mencius Moldbug wants to return to 1750, but immigration supporters are turning back the clock 800 years. Nonlinear ethnic niches are harbingers of the reversal of centuries of social progress towards impersonal cooperation and economic progress towards larger, more homogenous, and better integrated markets. Economists who support immigration on the grounds that it increases market size have played themselves; mostly residing in countries (and operating in a field developed in those countries) that have been at the cutting edge of modernity for centuries, they’ve forgotten that the default state of mankind is kin and clan based, and are playing handmaiden for the return of that mode of social organization to the West and consequent balkanization of national markets.

The good news is that nonlinear ethnic niches are almost all confined to recent immigrant ethnic networks. Ethnic networks in politics can last in perpetuity, but in US business tend to break down in a couple of generations. Owning a small business is tough, and later generations who are assimilated into US culture and language often prefer education and the professions instead. Low fertility means it only takes a few defections from the ethnic business to decay it away.

The bad news is that this breakdown only happens if immigration is stopped. As long as migration from the old country continues, ethnic networks maintain their sense of apartness from broader American society and can continue to lock down their niches and take over new ones. There is no upper limit to this process. Until that changes, India awaits.

Albanian nationals have an arrest rate of 209.8/1000 people in Britain today, 17.5 times the British national rate.

There’s also the innovation case, but this only applies to a small fraction of immigrants (say, those above 110 IQ) and ideas can cross borders even more easily than goods; Iceland is not generally less technologically advanced than the United States.

This is one of the reasons I find the anti-immigration right’s hatred for free trade counterproductive. There are many arguments against free trade in all cases (reindustrialization, maintaining process knowledge and industrial synergies, geopolitics, national defense, and favors for key constituencies all come to mind). But making internal market size, one of the top priorities of statesmen from Alexander Hamilton to Pyotr Stolypin to Hitler, irrelevant is an enormous boon to the cause of immigration restriction. The other big reason is that breaking free trade in the wrong ways causes enormous damage for no gain, and this is both very bad in and of itself and destroys the right’s broader credibility.

Before someone yells at me and says that Chicago was never homogenous, homogeneity is a gradient not a binary. In 1960, with the various white ethnic groups of the Ellis Island era in the process of fully assimilating after being cut off from their source countries and the only significant nonwhite group being American blacks, Chicago was much more homogenous than today. Substitute London or Birmingham if you want.

It’s also misleading to compare Mexicans to other immigrant groups, because Mexicans so utterly dominated US immigration for so long. More than half of all immigration to the US between 1986 and 2008 was Mexican, and Mexican fertility was much higher than other major groups too, allowing the formation of ethnic enclaves in which everyone you’d meet on an ordinary day is Mexican and hence every local sector was almost entirely staffed by Mexicans just because of sheer numbers. This is distinct from nonlinear ethnic niche formation, which serves a multiethnic clientele, but looks the same in terms of co-ethnic hiring.

According to Vaclav Smil, this intensive-over-extensive or thrift-over-innovation model is typically Asian. It is very good for excelling within a system, but very bad for creating better systems, which is the only route to long-term progress.

This is a perfect example of citizens, not Americans. Or “administratively American.”

As the common rejoinder in discussions of the “wage gap” between men and women goes: if women really are paid 25% less for precisely the same work, you could start a labor-intensive business that hires only women and become a billionaire, but no one does this. Instead, “women-in-X” pushes are concentrated in areas like academic STEM or the tech giants that are insulated from market forces. Mutatis mutandis with efforts to increase black, Latin American, or nonwhite hiring generally. The most well-known exception here proves the rule. In professional baseball, there was a period of decades in which some teams excluded blacks and others didn’t, and those that hired blacks first did much better, which is to be expected from the discrimination hypothesis.

I avoid mentioning Indians in the tech industry for this reason; although there are many, many anecdotes and allegations of Indians using these tactics in individual companies or departments (including celebratory accounts from Indians themselves explaining how they “conquered” Silicon Valley), the industry as a whole is too big, too prestigious, and too competitive for this sort of ethnic capture. Indian prominence here has more to do with the fact that a very large fraction of Indian immigrants are recruited from the top couple percent of a country of 1.4 billion on skilled-labor visas specifically to work in tech, and hence Indian-Americans are, on average, quite good at it. Ethnic networks for hiring and mentoring and VC capital do matter, and the latter in particular is why I’m suspicious of metrics like “numbers of unicorns founded,” but are not nearly enough to monopolize the whole sector the way Patels have for motels.

The First World productivity advantage derives from a mix of historical (capital accumulation) and cultural (meaning aggregate behavior, so I’m including both genetics and the legal system in addition to what’s commonly understood as culture here) reasons. These advantages are a collective property of the nation, not a rent and not derived from magic dirt, and are generally degraded by immigration, which is why this should not be used as an argument in favor of open borders. The accumulated capital of the past is spread more thinly across more people, and given the reality of deep roots, immigrants making the societies they move to more like the ones they came from, immigrants reduce American cultural advantages in the long run. In the case of nonlinear ethnic niches, the incredibly important WEIRD norm of impersonal cooperation is eliminated in captured sectors of the economy.

Parenthetically, businesses and other institutions should not be allowed to sponsor visas (labor, student). This is totally incompatible with republican or democratic government because it outsources the composition of the future demos to a smattering of special interests and privileges institutions with foreign ties over those without (which is ruinous to national cohesion). This practice was sensibly banned in 1885 under the Foran Act (AKA The Alien Contract Labor Law), but has since resurrected itself. If Western countries had an apartheid-style system that totally excluded immigrants and their descendants from positions of power, it might make more sense, though I would still oppose it for the same reason free-soilers opposed slavery; it’s bad for the moral character of owners to rely on a disenfranchised caste of foreigners with fewer legal rights, even if it’s a win-win transaction for the businesses and the foreigners themselves. If we must have labor visas, they should not be tied to a specific employer and workers on them should have full rights regarding switching jobs (and have to pay payroll tax, which nonresident aliens on the OPT visa presently do not, making them artificially cheaper for a given level of productivity).

I don’t want to overstate this. These privileges are accessible to every group in the US except for white men, but there are no comparable black networks (except for those in municipal governments, but that’s a different story) and very few Latin American nonlinear ethnic niches outside of organized crime. I think the fact that Spanish is so common is part of this. Because there are so many Spanish speakers from many different ethnic groups in the US, you don’t have the language barrier providing a mechanism for informal ethnic separation from outsiders and hence the closure of employment networks that helps these niches sustain themselves.

See this 1995 article about a Gujarati businessman using Florida’s minority entrepreneurship incentives to become a landlord risk-free. Gujaratis do not dominate real estate, but they have the same political advantages they do elsewhere, and use them.

Outside of maybe tech, but the zero-marginal-cost, winner-take-all nature of tech means startups cannot possibly replace small businesses as a route to the middle-class for large numbers of people across the entire country.

Compare with immigration choking off another traditional American route of self-improvement, internal mobility towards booming economic centers.

Henrich would deny that Westerners are individually exceptional at all. He’s wrong on the world scale, but it is true that other groups (Eastern Europeans, Ashkenazi Jews, East Asians, some Indian jatis) are just as capable as individuals, but never managed anything remotely similar to Western takeoff, and have only participated in it by joining or copying Western institutions and cultural practices. Western civilization is far more collectively exceptional than Westerners are individually exceptional.

The lack of minority tax farmers (who could be relied on to efficiently extract from the peasantry and thrown to the wolves during inevitable backlashes) also forced the development of sophisticated tax collection apparatuses and the legitimacy to use them, which in turn both promoted limited and representative government and higher total revenues and hence state capacity.

Free trade between states does this too, but there’s a catch. While the gains from larger markets are positive-sum, they do not accrue evenly to all participants. From the perspective of the state, it’s OK if one part of the nation gains more than others, since all contribute to national power. But a rival state gaining relatively more is dangerous; see US/China right now for a current example. Geopolitics, unlike prosperity, is zero-sum.

Parenthetically, the ability to formally organize on behalf of ethnic and racial interests is the most important quasi-aristocratic privilege nonwhites have in the United States. Affirmative action in college admissions gets the most attention, and its counterpart in government and corporate hiring, promotion, and contracting probably affects people more in the pocket book, but both of these are ways to gain advantage within pre-existing systems. The ability to freely associate and hence coordinate matters much more for affecting the parameters of the systems themselves, whether by lobbying, bloc-voting, boycotting, or other methods of exerting power. Try to imagine a “White American Hotel Owners Association.”

India takes Peter Thiel’s maxim that competition is for suckers and implements it at the biological level.

In the US, businesses push the labor shortage narrative to encourage looser immigration laws, but this isn’t really a factor in India outside of maybe Indian Bengal.

Note, however, that this is a long-run problem. In the short run, castes can leverage their networks to deliver goods and services more cheaply than out-caste entrepreneurs, much as with nonlinear ethnic niches in the US, or with monopolies generally. But by strangling competition, long-run improvement is stopped.

As evidence, a similar phenomenon occurs with marriage. Most people have a real, though not absolute, same-race preference, and hence marriage rates drop in more diverse areas because a larger fraction of the fixed-size social circle are not real spouse candidates.

Which is the correct unit of analysis most of the time, hence my focus on two local nonlinear ethnic niches; Patels don’t have to dominate Dunkin’ Donuts across the whole US to qualify, regional dominance is enough.

I can’t prove causality, but it’s worth noting that even unselected Indians descended from unskilled laborers from what is now the poorest part of India are several times more productive in majority-Indian societies without the caste system, such as Guyana, Trinidad & Tobago, and Mauritius.

Saying that Albanians don’t have an innate propensity for mafia activity is a bit of a stretch. As a Serb, all I can say is that England deserved each and every one of them — and more.

What about China (its Han core is still around 97%), Japan and Korea? I'm not well versed in their history, but all three seem like they have lacked the ethnic niches, specialised religious business-minorities or caste-systems that have bedeviled MENA, India and large swathes of Eastern Europe for most of their history.