Mind Viruses

In Defense of An Analogy

Are “mind viruses” real? The phrase is often attacked for lacking a rigorous definition or explanatory power1, but in short, yes. There is a valid analogy between pathogens that cause various illnesses and ideas that reduce fitness or function, one that can aid in both understanding and action2, and there are several well-studied examples of such mind viruses.

What is the claim behind the analogy?

The mind virus analogy makes the following three claims:

Like viruses, ideas spread from person-to-person. This is mechanism agnostic; persuasion, social pressure, economic or political coercion, education, and mindless conformism all qualify. All it requires is that being connected3 to another person spreading the idea increases the probability that you yourself begin to spread it or act in accordance with it.

Like viruses, ideas can reduce fitness4 (number of surviving offspring) and function (execution of adaptations).

Those ideas that fit requirement (2) can still spread5.

What does the analogy not claim?

The mind virus analogy does not claim that a mind virus must operate independently of other factors such as genetics, technology, geopolitics, law, or economics. Susceptibility to actual pathogens can be very strongly influenced by all of these things, but the pathogen is still the relevant causal agent6.

What is the major point of disanalogy?

When discussing contagious diseases, the focus is on the person infected. But mind viruses are a social phenomenon; a person does not need to believe in an idea to be harmed by it. You can be, and often are, harmed by the beliefs of others. This is trivially true with regards to cases such as ethnic conflict, or anti-marriage beliefs7.

Strictly speaking, this is true of pathogens as well; a baby whose mother dies of the Black Death is not long for this world, even if not infected. But that’s not usually what we mean when we refer to the Germ Theory of Disease. When we speak of mind viruses on the other hand, we refer to the aggregate social effect of an idea, not just the effect that that idea has on the fitness of those who believe in it.

Case Study #1: The Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement

In 1856, a 15 year old Xhosa girl by the name of Nongqawuse in modern day South Africa claimed to have a spiritual experience while out scaring birds from uncle’s crops. She claimed that spirits had told her that if the Xhosa killed all of their cattle and destroyed their crops, the dead would arise and spirits would sweep the European settlers of South Africa into the sea8.

After persuading her uncle that she had seen a true vision, he managed to convince the paramount chief to do as she said, and he convinced the other Xhosa9. As a result the vast majority of the Xhosa slaughtered their cattle and destroyed their crops as she demanded.

As a result, the region was depopulated (from over 105,000 people to less than 27,000), and it is estimated that over 400,000 cattle were killed and 40,000 Xhosa starved to death. The survivors were forced by the threat of starvation to submit to the authority of the British (after 8 inconclusive frontier wars had failed to do so) and work for the European colonists as wage laborers. The depopulated land was distributed to European farmers, who were much less inclined to destroy their own livelihoods.

Did this movement affect fitness or function? Yes to both, as starving to death reduces surviving offspring and hinders the execution of adaptations (such as finding food). And did it spread from person to person? Also yes, from Nongqawuse to her uncle to the paramount chief of the Xhosa to the Xhosa as a whole. In this case, we also have a very good idea of what the mind virus itself is: kill your cattle and destroy your crops, and the white man will disappear. Unsurprisingly, destroying your food supply leads to starvation. And we can safely reject non-ideological explanations for the Xhosa’s actions; there is no plausible economic or genetic reason to starve yourself to death. The Xhosa cattle-killing movement is thus a crystal clear example of a mind virus in action, one so deadly that it destroyed an entire society10.

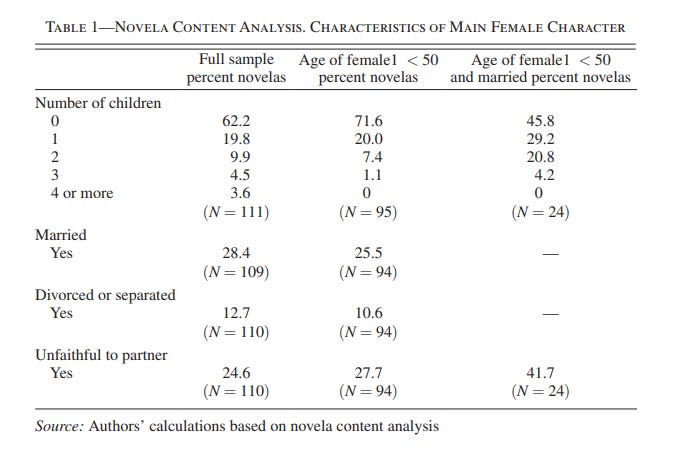

Case Study #2: Brazilian Soap Operas11

Popular media affecting fertility is something generally accepted among demographers, but it can be difficult to precisely quantify the effects due to the nebulous nature and inherent complexity of the subject. But it’s not impossible. One group of researchers took advantage of the fact that one television group, Rede Globo (the fourth largest television group in the world), had a near monopoly on soap opera production in Brazil12 to investigate the effects of a single genre, soap operas, on fertility. By exploiting the differential rollout (with timing being down to idiosyncratic patronage decisions) of Globo throughout Brazil and using 12 years of individual-level Brazilian census data (1979-1991), this group was able to estimate the direct effects of soap opera access on fertility. They estimate that Globo access was responsible for 7% of Brazilian fertility decline over this period. This is not trivial, equivalent to ⅔ the effect of increasing education over the same timeframe.

The result is robust to controlling for various area characteristics, and passes a number of other robustness checks13.

The authors also demonstrate that it appears to be the Globo telenovelas in particular, and not TV access in general, that is responsible for this effect. In particular, the effect is stronger in areas where more children are named after telenovela characters.

The precise mind virus is harder to identify in this case than with the cattle-killing movement. The link between killing your cattle and starving is obvious, but the link between soap operas and lower fertility is not. So what’s the mechanism here? Female soap opera characters were, compared to actual Brazilian women, much more likely to be single, cheat on their husbands, divorce, and be childless or have a small family. They were also much more likely to be middle class and upwardly mobile.

I postulate that the effect mainly operates by (1) weakening marriage (by increasing the perception that adultery is rampant and morally fine) and thus making it harder to form stable unions and (2) lowering desired fertility by associating low fertility with desirable things like middle class status and upward mobility. The authors don’t provide the data to test the first hypothesis, but they do test the second one, and find that the effect is indeed stronger in years when social mobility is a major theme, as well as being stronger among women who are about the same age as that year’s female protagonist (and thus more likely to see themselves in a similar position).

So did Rede Globo soap operas affect fitness in late 20th century Brazil? Yes, as fertility and fitness are almost synonymous in a post-Malthusian world. Did they spread from person to person? Yes, from the creators and distributors at Rede Globo to their watchers, and, via feedback from viewership numbers, from the watchers to the creators and distributors. And the authors are careful to exclude plausible alternative explanations for this effect, so we can be confident in causality. This makes late 20th century Brazilian soap operas an example of a comparatively benign mind virus in action.

Case Study #3: French Secularism

The fertility component14 of the first modern demographic transition began in France15 around 1760, and spread from there. This is a problem for most conventional accounts of the demographic transition, which emphasize economic progress, literacy, education, and lowered mortality as the major causes, because France lagged on all of these compared to its neighbors in Britain or the Netherlands, which did not begin their demographic transitions until more than a century later.

So what caused this precocious fertility collapse? A French demographer, Guillaume Blanc, used a historical crowdsourced genealogical database with a sample size of millions to assemble an array of evidence pointing towards an ideological/cultural cause, specifically Enlightenment French secularism. In particular, the presence of refractory clergy is extremely strongly correlated with timing of fertility decline; regions of France with the highest levels of refractory clergy transitioned about a century after those with the lowest, at the same time as Britain. Similarly, the proportion of secular wills is very strongly correlated with fertility decline. This is true at both the region and individual level.

This result is robust to multiple checks, and remains incredibly strong even after accounting for the non-secularism cultural impacts of the Enlightenment, population density, literacy, income, urbanization, language, state legitimacy, pre-secularization religiosity and even unobservables via time and region fixed effects. These effects also apply to second generation migrants, who are affected by the characteristics of their parent’s region16.

Further evidence for a cultural explanation comes from the fact that in the 19th century, this wave of low fertility spread to culturally similar (as measured by linguistic distance from French) municipalities first, even outside of France itself.

In this case, our mind virus is secularization17 (specifically: the loss of moral authority on the part of the post-Counter Reformation Catholic Church), which reduced French fitness by reducing marital fertility. It spread via the well-attested mechanisms of the historical Enlightenment.

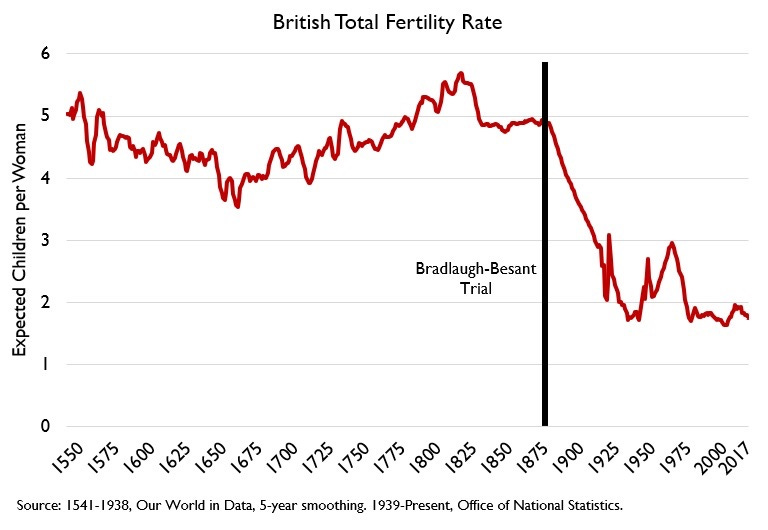

Case Study #4: Bradlaugh-Besant

The British demographic transition began just over a century after the French. Why then, and not earlier (as one might expect from Britain’s early urbanization and industrialization) or later (as one might expect from the German or Danish example)?

The answer appears to be linked to a famous trial that took place in 1877, known as the Bradlaugh-Besant Trial. This trial was about whether or not a new edition of a book entitled The Fruits of Philosophy, which included a number of contraceptive techniques and advocated family planning as morally desirable, could be legally sold in the United Kingdom. The book had been available in Britain since 1834, but never sold many copies. The 1875-1876 edition, however, was censored on the grounds that it contained new obscene illustrations of female anatomy. Two secularist activist reformers, Charles Bradlaugh and Annie Besant, took the opportunity to go to court, both to mainstream their views on family planning (which was taboo in Victorian Britain at the time) and to challenge the state’s powers of censorship.

The trial received enormous attention in English-speaking newspapers both in Britain and around the world, but little in other languages, and sparked a vigorous debate over the morality of family planning, as well as a massive increase in the sales of The Fruits of Philosophy. The Malthusian League, an organization dedicated to population control, was established in the immediate aftermath of the trial, and a flood of new literature on population control was written and distributed.

We can be confident in causality, for a few reasons. First, within the UK, fertility decline was steepest in areas with the highest coverage of the trial, and this result holds after accounting for the various expected confounders (such as general newspaper coverage, area-specific effects, or marriage rates). Notably, trial coverage does not predict fertility before the trial.

The effect is also robust to dropping various portions of the sample, such as areas concentrated in specific economic areas, urban or rural areas, or Wales, as well as controls for being near London or having high news coverage generally.

Furthermore, the effects were not confined to the United Kingdom. Anglophone Canada also faced a steep decline in fertility at this time, while Francophone Canada did not. This is the cause of the “revenge of the cradles” that allowed Quebec to maintain its stature within Canada despite massive Anglophone immigration.

We can exclude Quebec-specific effects, because the decline in fertility was concentrated among the British-origin everywhere in Canada, including within Quebec itself.

A similar pattern appears in both South Africa and the United States. Immediately following the trial, British-origin South African whites experienced a steep fertility decline, while Afrikaner whites did not. In the United States, British origin whites saw an immediate fertility decline, while whites from other countries did not. In Canada, South Africa, and the United States, the mechanism is the same as in Britain: lower marital fertility, with couples choosing to stop having children early. This provides very strong evidence for a cultural/ideological cause, because South Africa, the United States, Canada, and Great Britain had different economic and legal structures. Seeing the same effects, at the same time, in culturally similar (Anglophone British origin whites) groups in proportion to their exposure to Bradlaugh-Besant, but not in linguistically dissimilar (but genetically almost identical) groups in the same countries18 facing the same economic and legal environments is strong evidence for the cultural interpretation.

Notably, the information on contraception mentioned in The Fruits of Philosophy was already widely known (crude condoms, withdrawal, abstinence) or factually wrong19. This is backed up by the fact that methods of contraception did not change after the trial. The mechanism by which the trial reduced fertility was not by providing new information on contraception, it was by mainstreaming the idea that family planning was desirable. This is supported by the fact that the newspaper debates on the subject overwhelmingly focused on the morality of family planning, not on the contraception methods themselves.

We can identify the mind virus itself: the idea that family planning is not morally wrong. The mechanism of spread investigated in this paper is via newspaper and via the book The Fruits of Philosophy, though we can safely assume the ideas were also spread via the normal mechanisms of social spread, such as informal conversation and debate. And we can identify the mechanism through which it reduced fitness: lowered marital fertility20.

Conclusion

Mind viruses are real and can have massive effects. Does this analogy suggest any courses of action? Yes. In the same way that one might use quarantines to stop an actual virus, you could partition the noosphere to avoid picking up mind viruses via a language barrier. This is a strategy used by the most successful “breeder cults” in the United States, the Amish and the Haredim. The problem with this strategy is that you also deny yourself access to beneficial ideas, information about the world around you, and a voice in broader affairs. Furthermore, this strategy requires a pre-existing community with high ethnic cohesion and an outsider mindset rather than one that can be done by an individual or single family.

For an individual, it’s best to be careful about what ideas you let in your head. Ask yourself, consciously, if your strongly held beliefs help or harm you and those you value. Unfortunately, such an individualistic approach cannot help with the social aspect of mind viruses; the beliefs of others matter to you. From a political perspective, social media is a problem in part because of its tendency to incubate and very rapidly spread mind viruses. It’s not obvious what the solution is21, as centralized censorship is extremely vulnerable to bad actors, generally undesirable in and of itself, and bad in most other contexts.

The key point is this: ideas matter, and can shape the course of civilizations. Ignore them at your peril.

Further Reading

Guillaume Blanc’s work on the early French demographic transition is generally excellent and highly recommended if interested in demography. Here’s the paper on secularization (relied on heavily in case study #3), on the additional benefits gained from the fine-grained information obtained via crowdsourcing genealogies, and a case study on a single French village, showing fertility decline predated the French Revolution or major changes in literacy, mortality, or social mobility.

The paper on demonstrating the importance of the Bradlaugh-Besant trial to British fertility decline. Also highly recommended. Cremieux has written a summary of the paper’s findings if interested, but I think he overemphasizes the importance of information on contraception and underestimates the importance of the moral aspect (which the paper itself does not do).

The paper on Rede Globo and Brazilian fertility, as well as a Twitter thread I wrote summarizing it. Recommended because I believe it the single most rigorous paper in the “mass media effects on fitness” genre.

Demographic Transitions Across Time and Space, a paper showing that demographic transitions are better modeled as a combination of economic factors (mortality, GDP per capita, urbanization, literacy) and contagion from already-transitioned countries then they are as one or the other. The explains the phenomenon of “sped-up” transitions today, as more recent transitions happen faster in time and at lower levels of development, as there are more and more countries to acquire contagion from. Contagion likelihood is predicted by physical, linguistic, religious, and legal distance. I believe this is a general demonstration of mind virus effects on fitness in the modern context.

Mind Viruses are Fake, Propaganda Isn't, an article written by Charles Angleson. I think the disagreement here is partly terminological. I define “mind virus” in broader terms using the three criteria above, whereas Charles distinguishes “mind virus theory,” as something that emphasizes the importance of public debate, from “propaganda theory,” which emphasizes top-down propaganda (propaganda would fall under my definition of a mind virus provided that a higher fraction of one’s peers believing increases the odds you believe it), but there is substantive disagreement as well. I think case studies #1, #3, and #4 pass the “public debate leading to fitness-reducing behavior” test, though case study #2 might not. Still, it’s a great article filled with good information, graphs, and references, so I’d recommend reading it (and subscribing to him).

I suspect some of the hostility towards the phrase comes from the fact that “mind virus” sounds kind of dumb, like something Rush Limbaugh would say. Unfortunately, I don’t think there’s a great alternative term; I like “hostile memeplex,” but it really isn’t any better.

On a social graph, not in physical space like with an actual pathogen.

I am not arguing that maximizing Darwinian fitness is the sole determinant of good, or that number of surviving offspring ought to be your sole utility function.

It is possible to imagine a world in which only fitness-enhancing ideas spread, while people rationally choose to avoid fitness-reducing ideas. But we don’t live in that world.

For instance, in 1933 the heritability of tuberculosis infection was around 0.8, as high as height today. Does this imply tuberculosis is a genetic disease? No, it’s caused by a pathogen. When almost everyone was exposed to this pathogen, susceptibility was mostly a function of genetics, but once the environment (particularly medical tech and living conditions) changed, heritability plummeted, reaching around 0.38 by 1978 (and almost certainly much lower today).

You may be pro-marriage, but if a higher fraction of your prospective partners are anti-marriage, you are still harmed.

This is a good place to emphasize that mind viruses are highly dependent on the societies they exist in. If someone were to tell contemporaneous Texas cattlemen to slaughter their herds to drive away the Comanche, they would be laughed at. But this is true of pathogens as well, as the near elimination of many infectious diseases after WW2 shows.

Note that the Xhosa did not have a state. He did not and could not coerce other clans into following Nongqawuse’s predictions, and indeed, even the clans living under British sovereignty (against the advice of their British magistrates) followed her.

Leftists, of course, now view this outbreak of insanity and autogenocide as “early form of black consciousness and resistance” ie, as a good thing.

Source I’m basing this off of is at the link, as with the next two sections. If you have a methodological quibble, I highly recommend reading the source first.

Brazil's demographic transition was extremely rapid, with TFR dropping from 6.3 in 1960 to 2.3 in 2000 to 1.66 in 2023. This without any active state-enforced population control measures and with abortion (and, for a time, even advertising contraception) illegal.

For instance, the effect begins precisely one year after the introduction of Globo TV, future fertility does not predict Globo access, and Globo presence in neighboring areas does not predict fertility.

Not the mortality component, which began later. These things are connected, but not synonymous.

France had a population of 30 million in 1800, double the population of what is today Germany and triple the population of Great Britain. World history would look extremely different (we might all be speaking French instead of English) had France matched Germany or England’s 19th century population trajectory.

We can be confident this is not a genetic effect due to the time controls and robustness checks. For instance, Quebecers are overwhelmingly descended from the Normandy/Paris area, some of the earliest secularizing areas, but did not secularize for 200 years after being cut off from France in 1759, and retained correspondingly high fertility.

Again, I have to emphasize that inclusive Darwinian fitness is not a utility function. Calling secularization a mind virus is not saying that it is bad.

Or in similar Northwestern European countries, whose demographic transition timings are usually off Britain’s by decades, or more than a century in the French case.

Spermicidal zinc douching does not work well, nursing does reduce the probability of conception, and the book provides erroneous information on what points in the menstrual cycle minimize the odds of conception.

Contrast this with the cause of the Baby Boom, which was more and earlier marriages rather than higher marital fertility. The first demographic transition is mostly about lower marital fertility, the Baby Boom and second demographic transition is mostly about more or less marriage.

It might be worth taking inspiration from Haredi social media filters.

Excellent piece.

Cognitohazards. I think the SCP fiction writers coined the term. LLM Psychosis is another cognitohazard.