Communist Pronatalism

Making Feminism Work

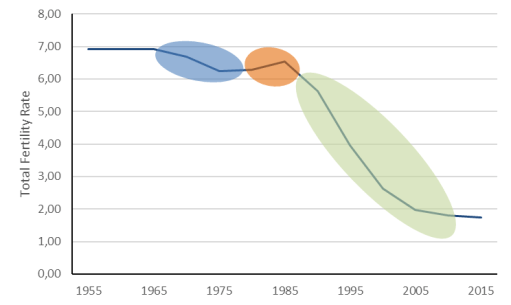

No one seriously disputes that state policy can lower fertility. Consider the case of Iran. Like many Asian countries (India, China, Singapore, South Korea) concerned about overpopulation, Iran started a population control policy in the 1960s. The Iranian Revolution initially reversed this on the grounds that it was incompatible with Islam. But even the Islamic Republic could do math and see that Iran’s agricultural land was nowhere near sufficient for a population in the hundreds of millions (especially cut off from Western agricultural technology and expertise), and so sharply backtracked in the 1980s, leading to the fastest fertility collapse in history1.

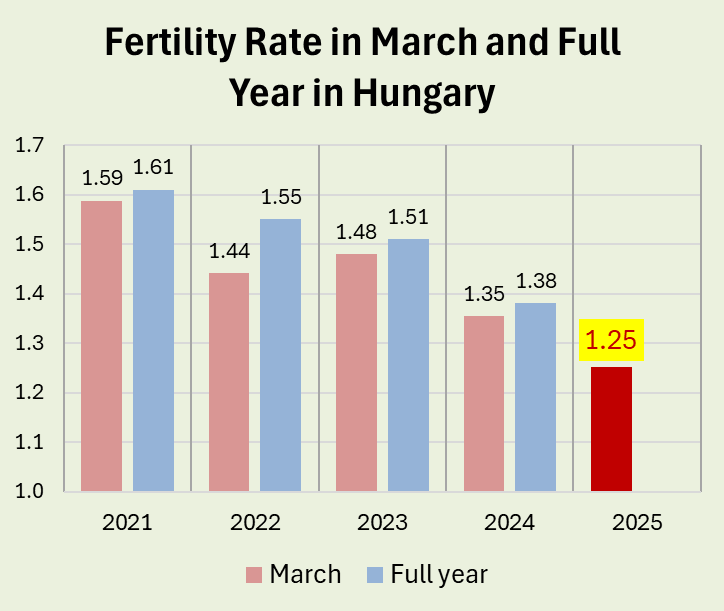

But it’s undeniable that state pronatalism in the 21st century doesn’t work well2. Hungary spends about 5% of GDP on fertility programs, including large financial benefits (70% of median wage) to new mothers, large tax credits for mothers (including income tax exemption up to the median income for mothers under 30 and full income tax exemption for mothers with four or more kids), and subsidized loans (both free-use and for housing, scaling with the number of kids) and savings, plus free IVF.

France has already implemented most of the modern pronatalist wish-list (including reducing income tax rates based on the size of the household, cash payments to mothers at birth, cash allowances for families, subsidized child care, universal paid parental leave, school cost payments, and housing subsidies for families with three or more children), although many of these programs are means-tested, and the French state has been ideologically pronatalist since the interwar period. In total, France spends about 3.6% of GDP on family programs, rising to 4.7% if you account for the indirect income tax adjustments and pensions benefits, the highest in the OECD.

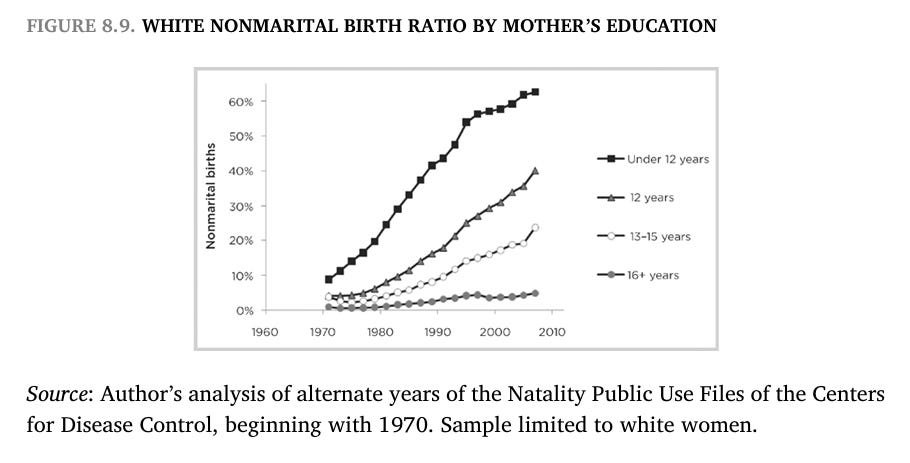

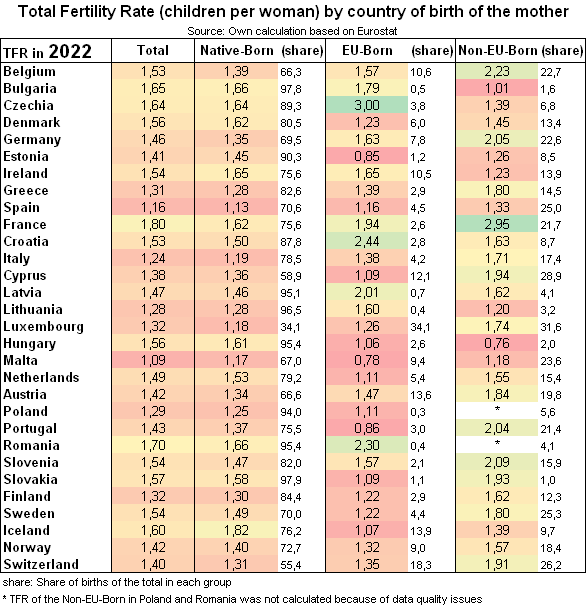

France does have the highest fertility in Europe… but this is because of the exceptionally high fertility (TFR: 2.95) of non-European immigrants (21.7% of total births). Rather than bring French fertility to replacement, the French pro-natal state overwhelmingly subsidizes large families in the massive African and Arab population (which makes the problems of population decline worse, not better). Contra the Age of Malthusian Industrialism hypothesis, French native fertility (1.62) is on the high end for Europe, but by no means exceptional. And while it’s impossible to say exactly how much because France does not keep ethnic or racial statistics, even this is probably increased by second-generation and beyond Africans and Arabs, since France has a much longer history of significant non-European immigration than other European countries.

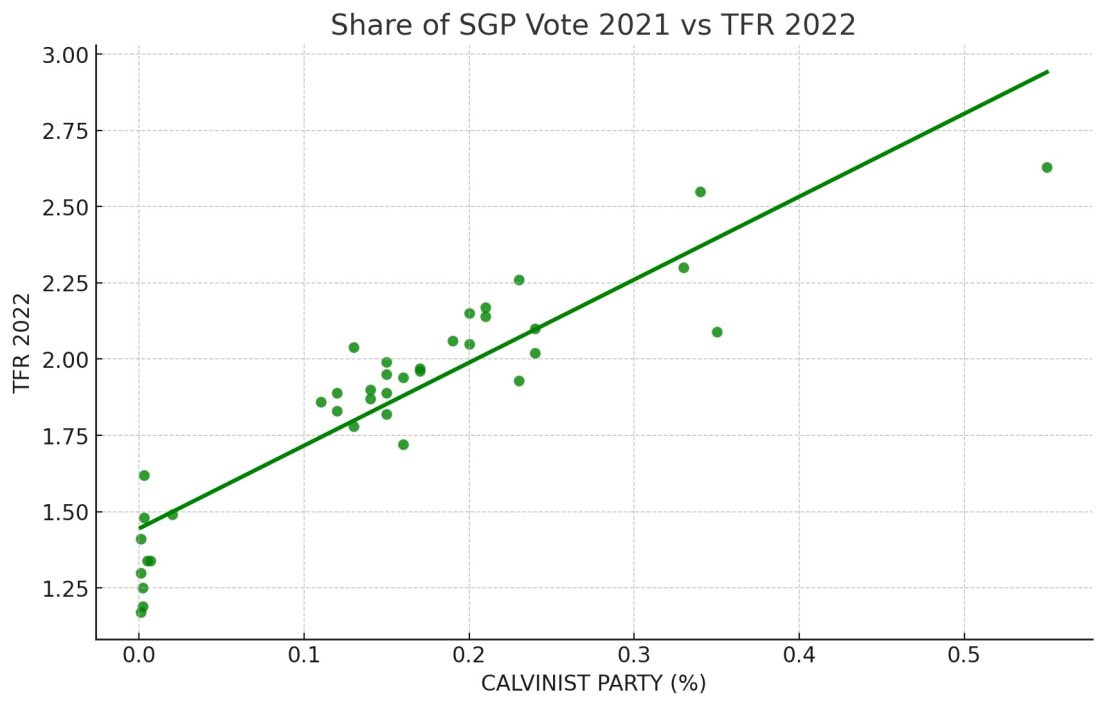

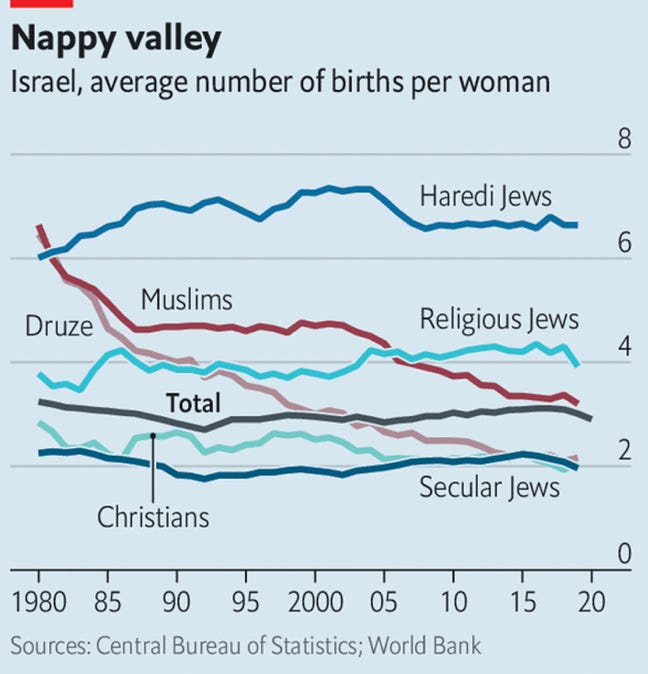

The only really effective high-fertility groups in societies sophisticated enough to maintain telecommunications infrastructure and modern medicine are patriarchal and pronatalist religious groups, often separated from mainstream society by technological choices or language barriers. Some examples are the Haredim3, practicing non-ultra Orthodox Jews4, the Amish and similar groups, orthodox Dutch Calvinists (strict enough to oppose women’s suffrage), and Finnish Laestadians. As a rule, the more culturally separated from mainstream society, the higher the fertility and the lower the attrition out of the group.

However, there are some interesting historical exceptions to this rule in the Cold War Eastern Bloc. Eastern Bloc Communist governments saw their people as tools of the state5, not individuals and citizens valuable in- and of- themselves. A larger population meant more workers, farmers, engineers, and soldiers, the better to build socialism and defeat Western capitalist imperialism. This was particularly critical in command economies where growth came from increasing inputs rather than efficiency. Since large-scale immigration was not an option, several of these states tried to increase their subject’s fertility.

This impulse ran headlong into the fact that Communism was ideologically feminist and atheistic. Communist states promoted female entry into higher education and the formal workforce (during the first half of the Cold War, the fact that Western states didn’t do this was one of the distinguishing superior facts of the West pointed out by Soviet dissidents such as Solzhenitsyn), removed taboos on promiscuity, premarital sex and the legal status of illegitimacy, and destroyed the high-fertility religious groups so noticeable in the West. These social changes were not as complete as their post-60s Western counterparts because so much of Eastern Europe’s population was rural and backwards peasants (much more than peasants today, with their mobile phones and Internet access) partly cut off from the culture of the center, and these changes were top-down, not in any way organic6, but still greatly changed Eastern European life. While hormonal contraception was rare, abortion was incredibly common in the Eastern Bloc, essentially serving as a one-for-one substitute.

While nowhere near as successful as the Western Baby Boom, Eastern Bloc pronatalism is worth studying for two main reasons. The first is that the Eastern Bloc’s legal and political regime for governing sex relations was much closer to Western countries today than the Baby Boom-era West7. The second is that, unlike the Baby Boom, which was not planned and arose from the spontaneous interaction of the Western European Marriage Pattern and postwar prosperity, the Eastern Bloc pronatalist programs were state policy. It’s much easier to copy laws than to socially re-engineer society from scratch.

There’s another reason Eastern Bloc pronatalism is worth studying. After decades of strong antinatalism, the CCP has reversed course and is promoting marriage and larger families. It doesn’t matter much over the next couple of decades8, but whether China has a TFR of 0.9 or 1.8 might be the most important factor determining the second half of the 21st century. I don’t know if they will be successful; it’s very difficult to rebuild a large-family culture after an entire generation without them, and East Asia’s propensity for extreme negative-sum status grinding makes this even worse.

The Soviet Union

As the biggest, longest-lasting, and most important Eastern Bloc country, and the only one in which Communism was not imposed by foreign armies, the Soviet Union has the most important and complex history with family policy and pro-natalism.

In line with orthodox Communist views on the family, the early Soviet Union imposed both a Sexual Revolution and second-wave feminism from above. Specific initiatives included:

Paid maternal leave two months before and after childbirth (1917).

Women were given both the right and obligation to work in the 1918 constitution, with sex quotas introduced in 1920. Common marital property was abolished; this meant that a woman had no right to property officially owned by her husband and hence the product of household or subsistence work. To attain rights to possessions, women had to work for a wage in the formal sector. More sex quotas protecting women from being fired were introduced in 1922.

Legalization of homosexuality (1917).

Women no longer expected to take husband’s surnames (1917).

Abolition of the legal categories of legitimate and illegitimate children; children receiving the same rights both inside and outside of wedlock (1917). Paternity was recognized and enforced through the courts based solely on the request of the mother; the mother’s word alone was considered sufficient proof and a mother could receive child support from multiple potential fathers.

The introduction of no-fault, unilateral divorce in 1917. Women, though not men, were entitled to alimony after a divorce.

The Soviet Union became the first European country to legalize abortion in 1920 and provided them free of charge. By the mid-1920s, abortions in Moscow outnumbered births 3:1.

Unlike the 1963-73 Western equivalent, these changes were entirely top-down with no organic component and did not entail those making these changes (in this case, the Communist Party) giving up any power. Furthermore, the early Soviet Union was not nearly as connected and integrated as the Western world in the 1960s. The reach of the Soviet state in the countryside where the vast majority of the population lived was limited until collectivization began in 1929, which is when Soviet fertility really collapsed.

Recognizing in the 1930s that the Soviet Union desperately needed military and industrial strength, and that the disintegration of the family and collapse of the Russian birth rate threatened this, Stalin partly reversed these changes. His reforms included:

Abortion was banned except to protect the life of the mother (1936).

A 6% childlessness tax (1941) applying to men aged 25-50 and married women aged 25-45. To this was later added a 1% tax for those with 1 child and a 0.5% tax for those with two.

State allowances to mothers of large families (initially 7, later reduced to 3, children), and single mothers (1944). Note: single mothers in a country where 40% of prime-age men have been wiped out are different from than those in one with balanced sex ratios. These allowances were halved in 1947.

The official state recognition and encouragement of large families with medals, titles, and honors starting at five children and increasing in prestige with each child. Mothers with 10 or more surviving children were given the title “Mother Heroine” and privileged access to goods, public utility payments, and a state pension (1944).

In 1944, women lost the ability to appeal to the courts for alimony and recognition of paternity unless they were cohabiting in a registered marriage.

Divorce was made more difficult, requiring motives, a fee, a court obligation to attempt reconciliation between the spouses, and publication in the local newspaper (1944).

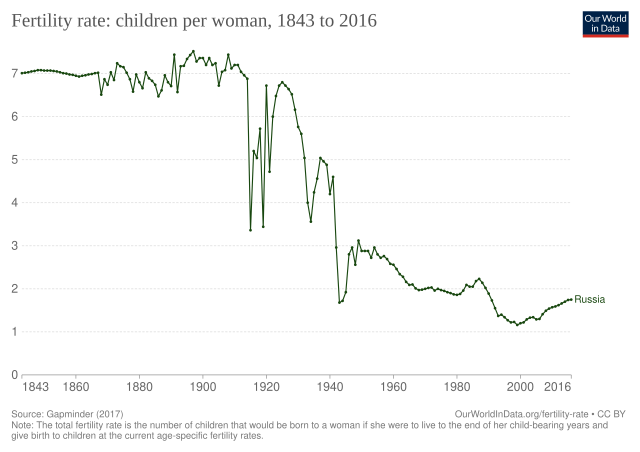

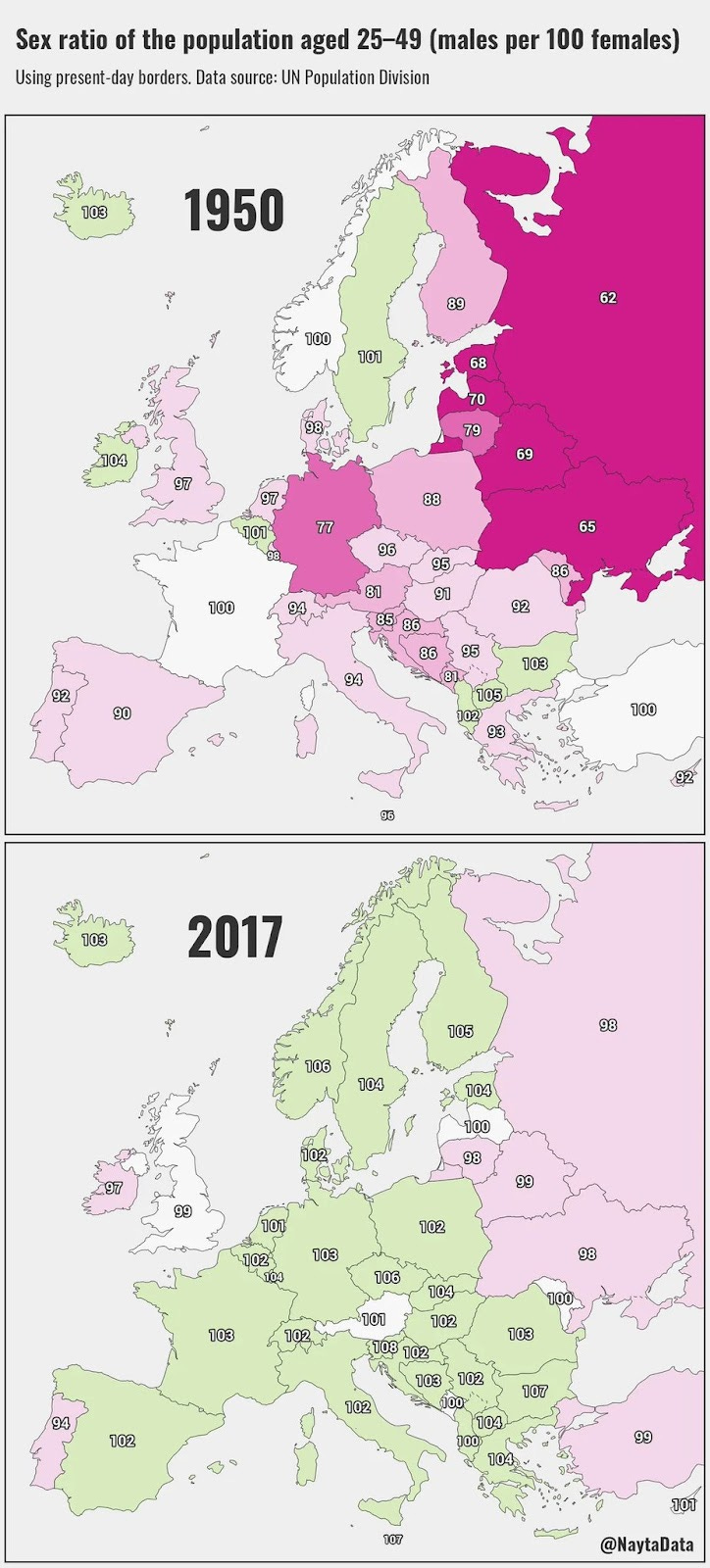

Soviet demographics were absolutely devastated by WWII, with about a third of adult men dying in the war and many more crippled. This greatly limited Russia’s postwar population boom, but Russia under Stalin’s pro-natal policies still maintained a TFR of around 3, which allowed a partial recovery.

As with many of Stalin’s reforms, some of these initiatives were rolled back with destalinization in the 1950s, and other pro-natal incentives were put in place. In particular, abortion and divorce were made easier, but the monetary incentives for children were increased. In this way, the post-Stalin Soviet pro-natal state came to more closely resemble its modern counterparts. Some specific changes were:

The re-legalization of abortion in 1955. Abortion quickly became by far the most important instrument of family planning once again.

Monthly allowances for children of men in obligatory military service.

Divorce made easier in 1969 by having them be confirmed by the Registry of Civil Deeds (ZAGS) rather than the courts, but still more difficult than it had been before 1944.

In the 1970s, pregnancy and maternity benefits (already equal to 100% of salary) were extended to all women regardless of employment record.

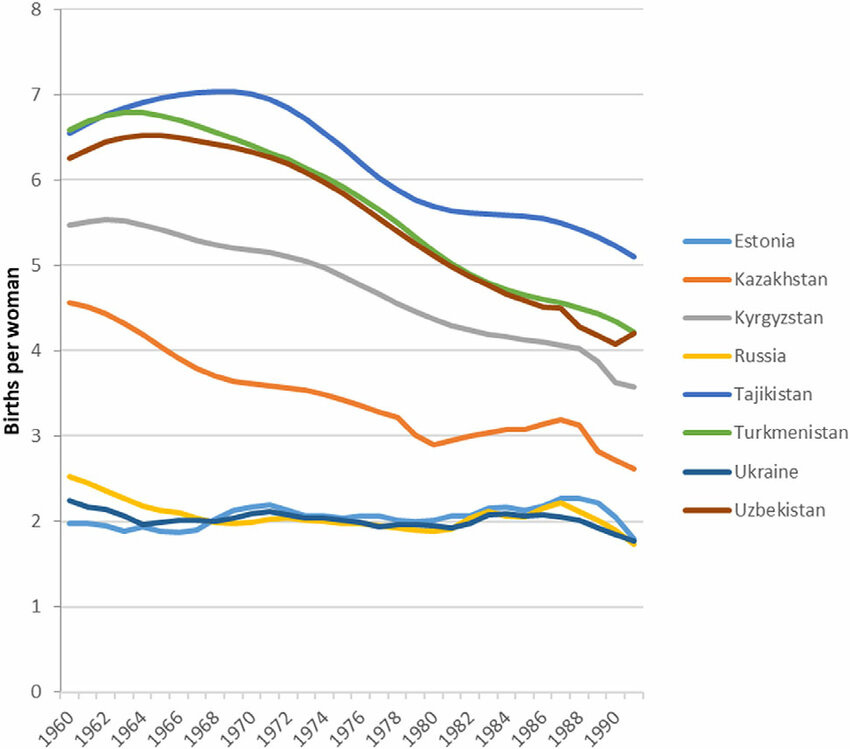

In this period, Russian TFR dropped from around 3 to around 2, where it remained until the fall of the USSR. While higher than the US or most other Western countries in the second half of the Cold War, this was still disappointing. In the 1980s, the Soviet state tried a couple of other incentives, namely more money and prioritizing young couples for housing.

Lump-sum of 50 rubles at first birth, 100 rubles for subsequent children for working mothers, 30 rubles for non-working mothers.

The USSR adopted a policy from East Germany in 1982 in which young married couples were given priority for rooms, and young married couples with children priority for apartments, as well as interest-free loans.

These seem to have worked better; Russian fertility noticeably rose in the last decade of the USSR despite a horrific economic situation. But Soviet pronatalist initiatives collapsed with the Union, and there was a 15-year interregnum with very little deliberate population policy in Russia. The modern Russian pro-natalist state is generous, but has little continuity with its Soviet equivalent and has the same flaws as its Western equivalents.

East Germany

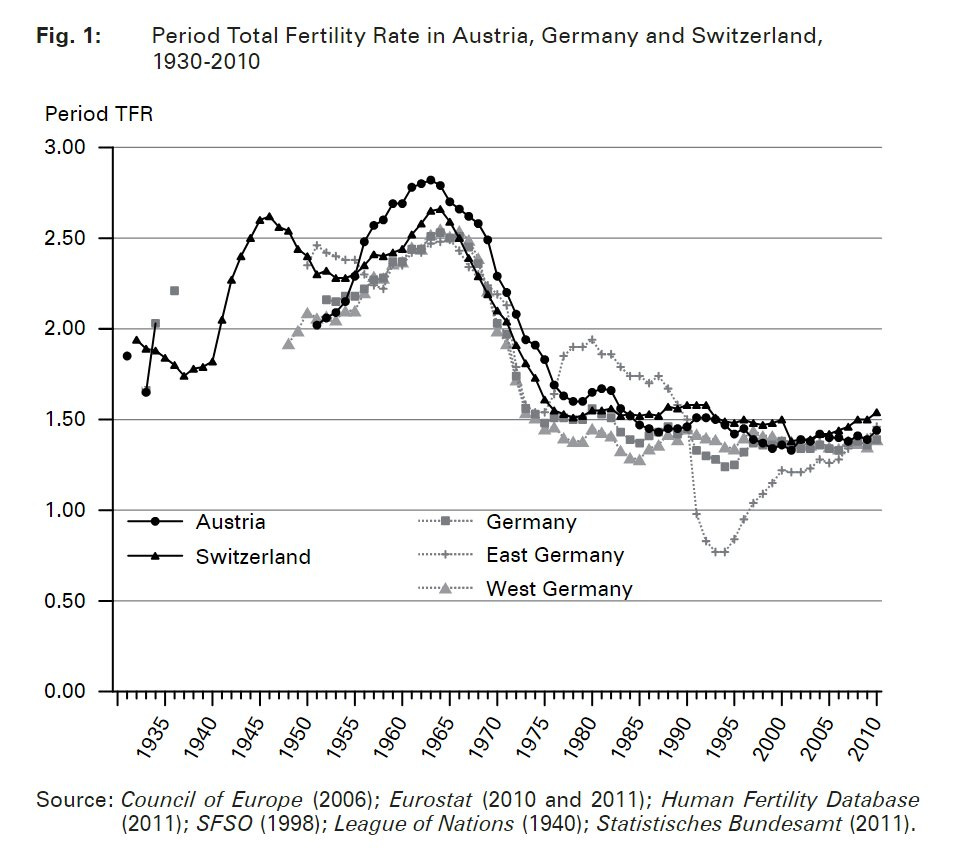

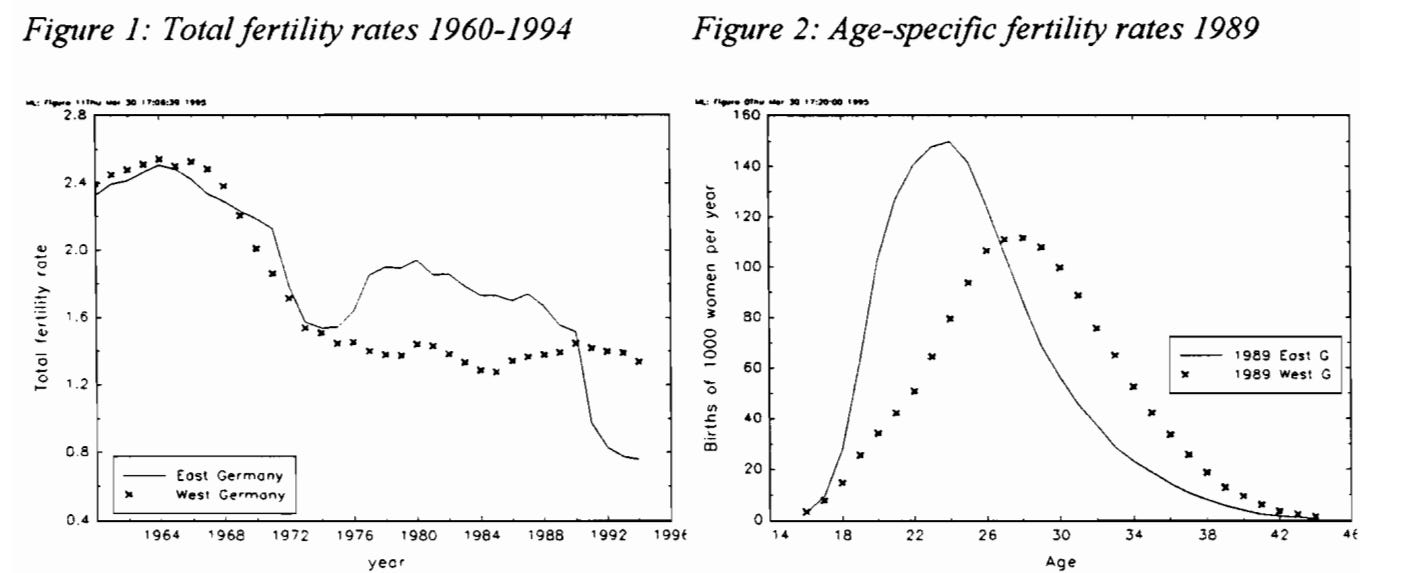

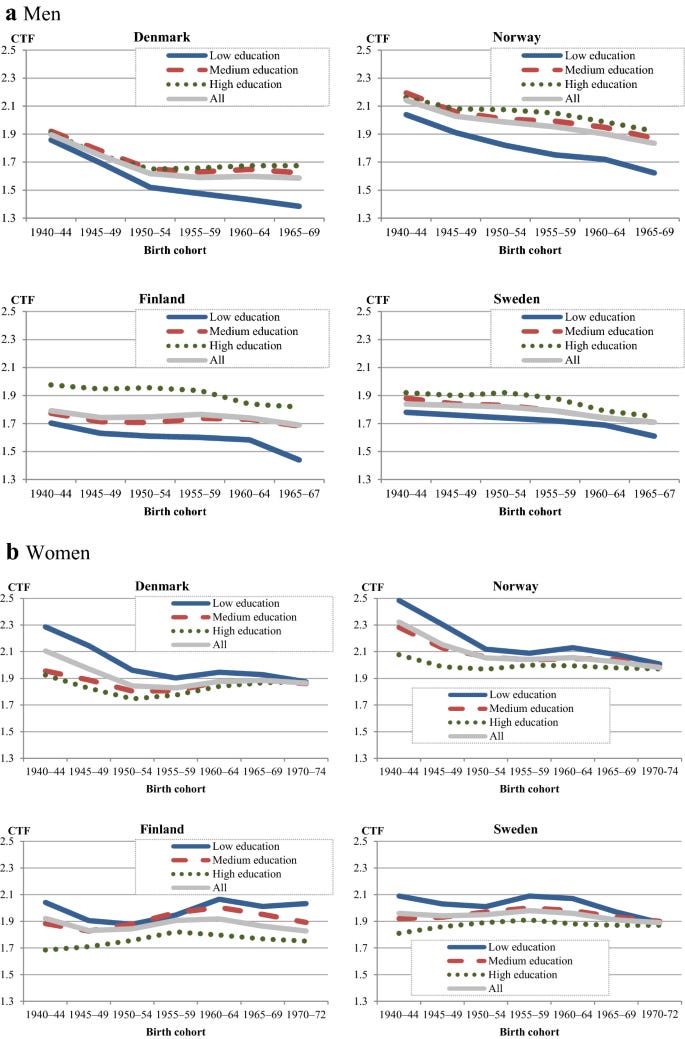

Fertility in the countries of Germanophone Central Europe followed very similar trends after WWII9. An anemic Baby Boom (which is why Germany, along with semi-Boom Italy and Japan, is one of the most aged countries in the world today), followed by the Second Demographic Transition collapse to one of the lowest TFRs in Europe. But East Germany is noticeably different, with significantly higher (though still below replacement) fertility between the end of the Baby Boom and 1990, then significantly lower from 1990 to 2008.

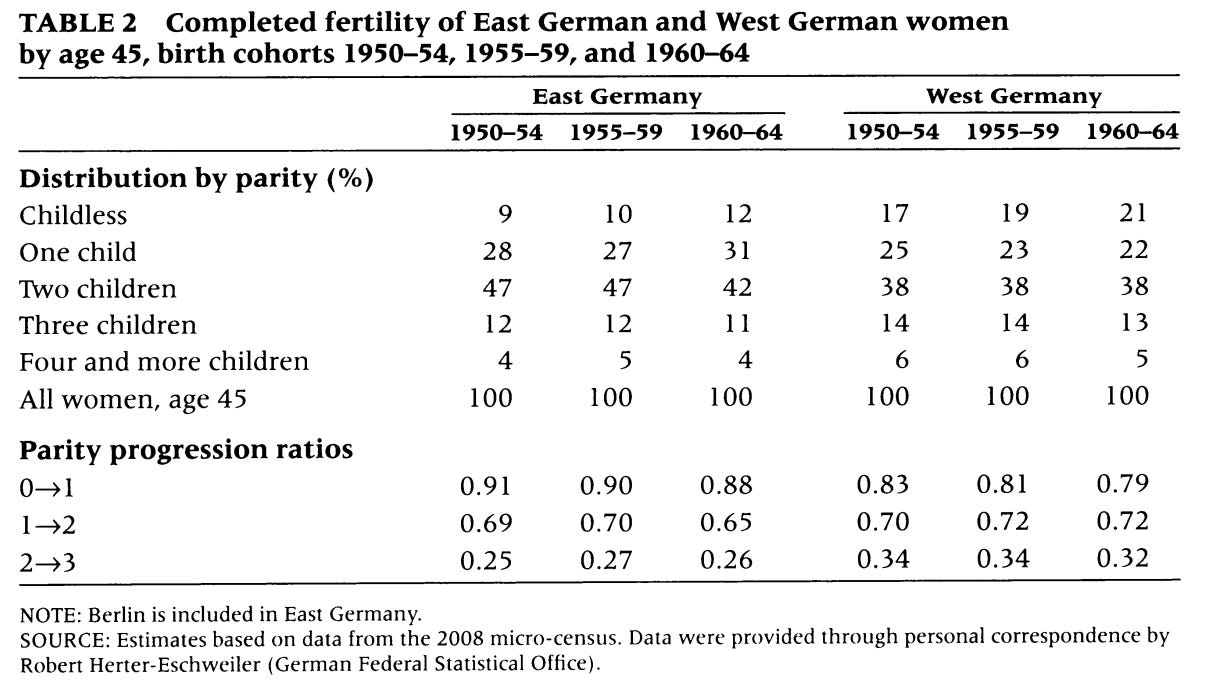

East Germany introduced several pro-natal reforms to combat fertility collapse. Financial incentives for marriage and birth (1972), free daycare for children over 1 year (1972), and in 1976, a “baby year,” one year of leave for new mothers after birth with full pay and a guarantee of keeping her job (Conrad et al, 1995). This seemingly worked, but with one big caveat. These measures were designed to promote large families, but East Germany had fewer large families than the West throughout this period.

The East German TFR advantage came from two sources. First, lower childlessness, peaking at 12% when the Berlin Wall fell, vs 21% in West Germany. And second, how early East German women had kids. Both the 1975-1990 advantage and the 1990-2008 disadvantage were partly timing10 effects, with East German women having kids earlier in the late Cold War and delaying fertility due to the post-reunification economic chaos. Average age at first birth in East Germany in 1989 was 22 (the same as in the US in 1970, and lower than it ever was in West Germany) vs 27 in West Germany.

The reason for both of these is simple: East Germany had a chronic housing shortage. You might think a housing shortage would reduce fertility, and it would in a market economy, but East Germany was a command economy where houses were rationed rather than sold. If you wanted to move out of your parent’s (tiny and cramped) apartment, you had to get married and have a kid. “In most cases, it was the only way to get an apartment in the state-controlled allocation system.” This strongly encouraged both early marriage and family, and was very effective at that, but did not encourage large families. By comparison, East Germany’s various baby bonuses and transfers to parents, which were designed to promote large families, did not work well.

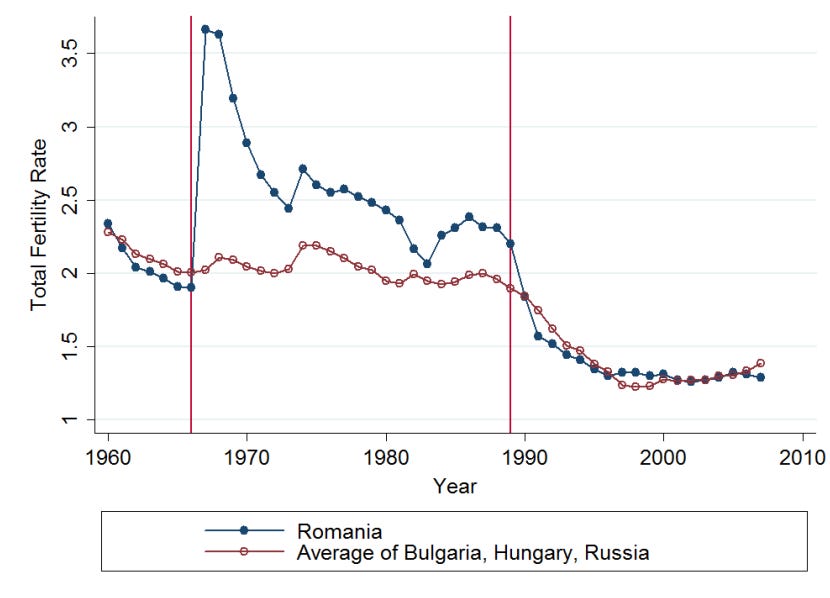

Romania: Decree 770

By far the most successful and infamous example of Eastern Bloc pronatalism is that of Romania. In 1967, Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu banned abortion in almost all cases (with exceptions for rape, incest, life of the mother, women over the age of 45, and women who already had large families). Modern contraception wasn’t banned, but was nearly impossible to obtain as the state ceased to import it from the West. This was enforced by monthly gynecological visits, with discovered pregnancies monitored to term. TFR nearly doubled from 1.9 to 3.7 in a single year.

The extraordinary initial increase was transient. The social structures and sexual norms of 1966 Romania relied on widespread abortion to manage fertility, and when that was suddenly banned people didn’t immediately change their behavior. As such, there was a short, sharp spike in births, with infamous social consequences (a massive spike in children abandoned at orphanages and maternal mortality ten times higher than comparable Eastern Bloc countries). But people adjust their behavior when conditions change. Romanians needed a few years to adapt to the new technological regime, but adapt they did, and Romanian fertility quickly came back down. Still, it remained persistently higher than peers until the collapse of the Eastern Bloc.

Ceaușescu didn’t just ban abortion and contraception. He also levied an additional income tax on childless individuals over the age of 25, as well as more common pronatalist policies such as family allowances scaled by the number of children (more money per child with more children), maternity leave and mandatory workplace nurseries, and pronatalist propaganda campaigns. By 1985, public expenditure on these material incentives was half the defense budget, in a state dedicated to eliminating the national debt. The Romanian bachelor tax was initially 10% on incomes below 24,000 lei and 20% on incomes above 24,000 lei, much higher than its Soviet equivalent, and may have been raised later11.

What Decree 770 shows is that it’s entirely possible for a powerful enough state with sufficient disregard for its subjects to raise fertility above replacement by brute force even with state atheism and second-wave feminism. Of course, Ceaușescu was the only Eastern Bloc leader executed after regime change, so this approach has its risks for would-be dictators.

Conclusions

I do not believe that Eastern Bloc pronatalism is either replicable or desirable, but I think the record of the various interventions they tried paints a clear picture of which ones worked and which ones didn’t. From least to most effective, you have:

Monetary transfers.

Medals, honors, and pro-natal propaganda.

Restricting housing to married couples, ideally with children.

Restrictions on divorce (Stalin only).

Completely banning all forms of abortion and contraception.

Unsurprisingly, the interventions closest to modern pro-natal states were the least effective. I believe the efficacy of China’s pro-natal efforts can be predicted by how far down this chain they’re willing to go (I claim no special knowledge about the inner workings of the PRC).

Appendix: The Flaw With Most Modern Pronatalism

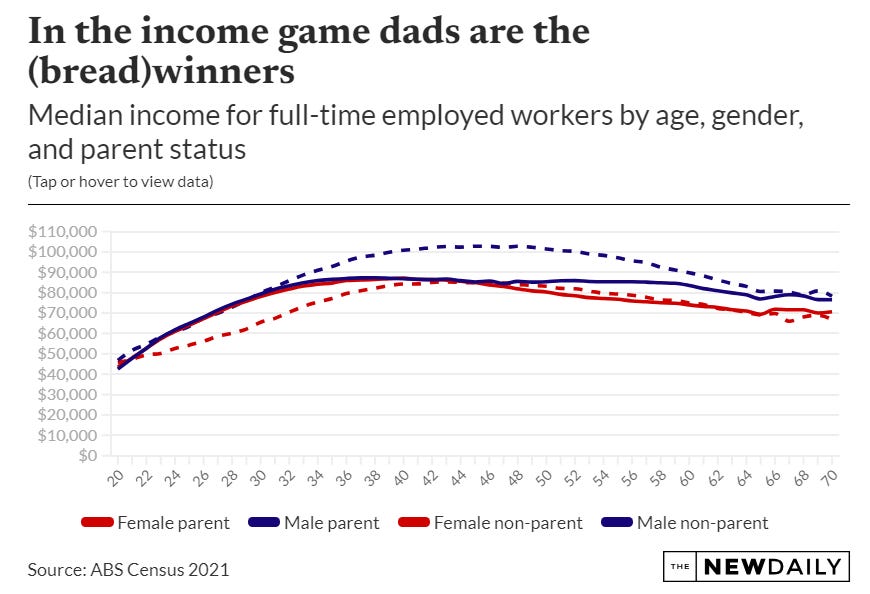

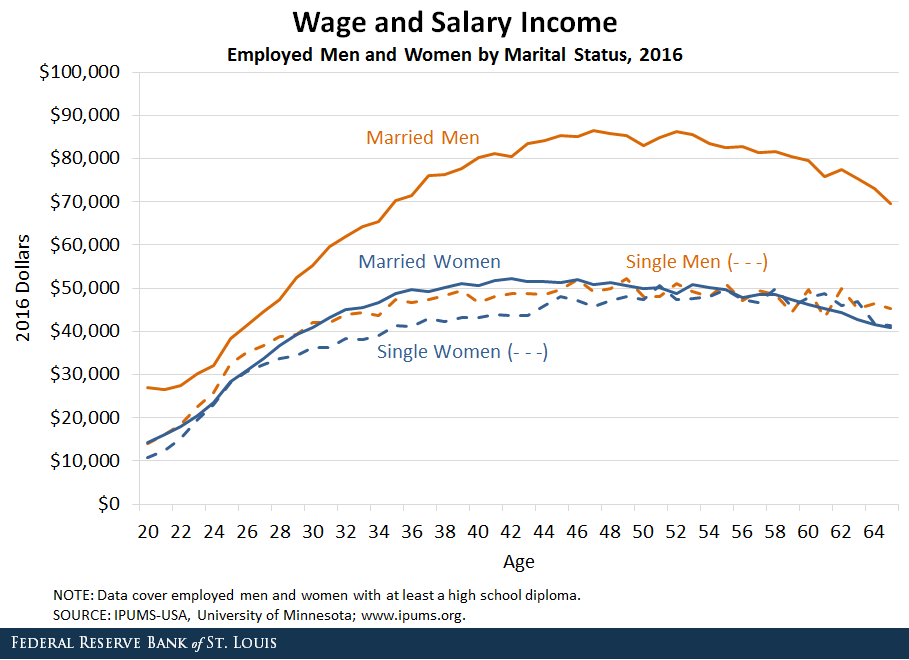

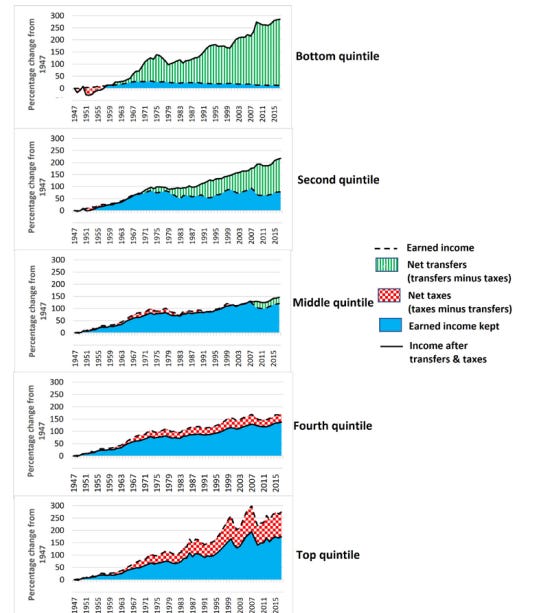

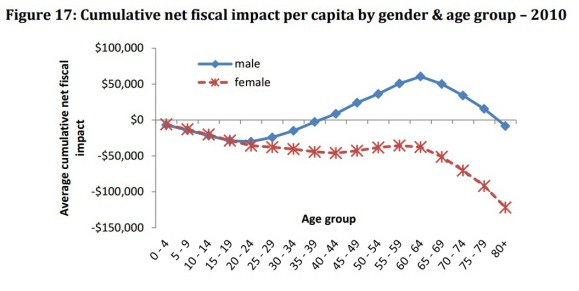

Most modern political pronatalist efforts and proposals, like JD Vance’s $5,000 Child Tax Credit, consist of some form of monetary or in-kind transfers (such as state-subsidized child care) to mothers. These transfers have to be paid for by taxes. Men pay most taxes12.

And not just men, but married (or long-term cohabiting) fathers.

But this is exactly the group for which income translates to more children! So you have a case where, to pay for pro-natal incentives, the men who need money for larger families have their income reduced and labor disincentivized via higher taxes. That doesn’t mean direct monetary transfers for children are totally ineffective, but the taxes required to pay for them very much work at cross-purposes with the intended goal. The high taxes required, and who they primarily fall on, is one of the explanations for why Nordic pro-natal states have largely failed.

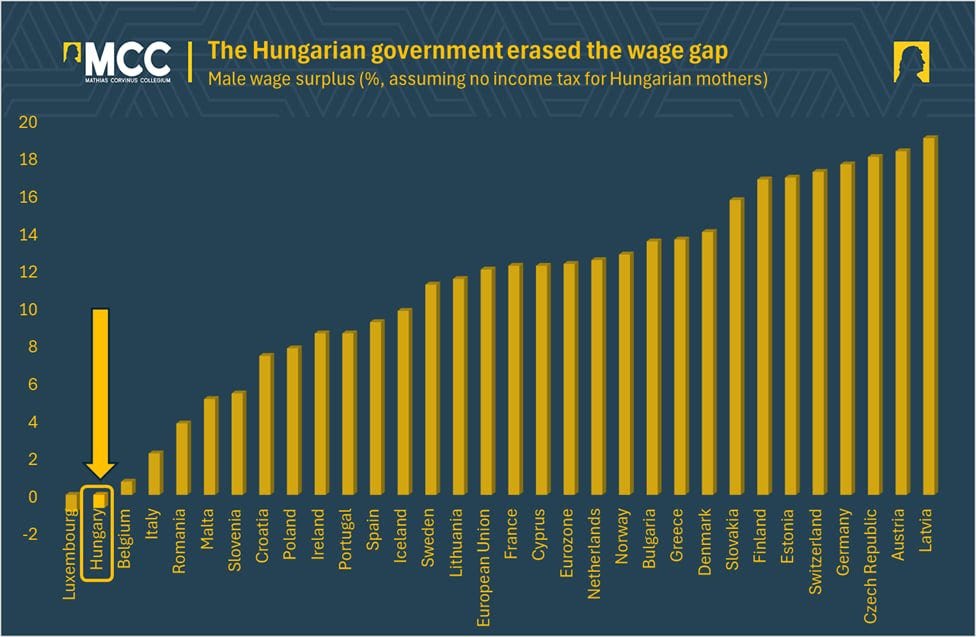

This is even more true for common pro-natal interventions aside from cash transfers. Consider Hungary, where women are exempted from income tax after a certain number of children, which in turn discourages the male-breadwinner family model and places the tax burden even more squarely on the shoulders of married fathers.

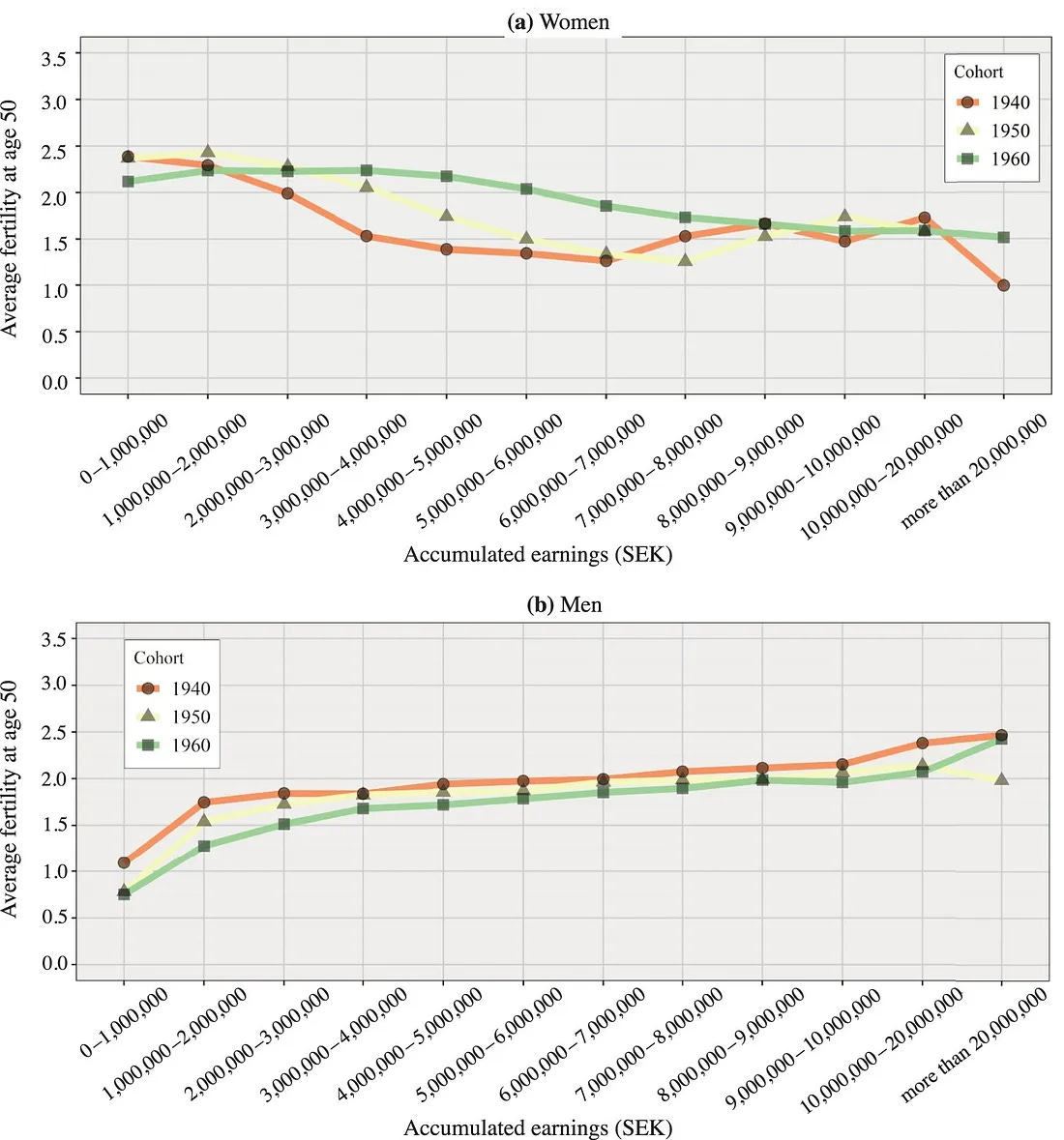

Most in-kind transfers, like free childcare, are even worse, because they increase female earned income, and the higher the lifetime earned female income, the lower the number of children.

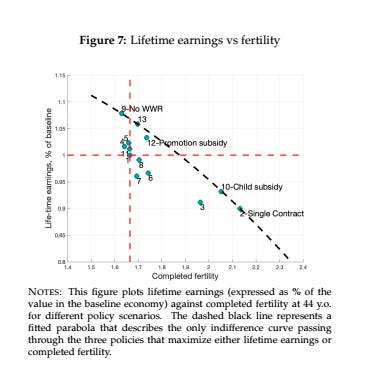

A recent study from Spain found a near perfect inverse relationship between how much a pro-natal program increased fertility and how it affected women’s earned income (only promotion subsidies did both).

So you effectively have a situation wherein the group for which income actually translates to children have their income reduced to pay for pro-natal incentives, which renders the latter much less effective than they should be on paper when they’re cash, and actively counterproductive when they’re in-kind. Just about all commonly-floated pro-natal policies fall into one of these two buckets.

The obvious response is that pro-natal policies and monetary incentives should focus on increasing men’s income, especially men’s earned income relative to women. If this isn’t politically possible, the correct thing for governments to do is nothing beyond enabling the proliferation of non-mainstream religious groups through opt-outs from public education. I’d note that the United States, with an unusually tiny pronatalist state compared to its European counterparts, has higher native and white fertility than almost every country in Europe.

Appendix: More Firepower?

One argument is that modern pronatalist efforts would work, but the numbers are just too small to achieve their goals, and that the solution is more money. Robin Hanson has proposed a $200,000 lump-sum payment per child. The US has about 3.6 million births per year, so this comes out to $720 billion per year. That’s a lot of money, but not so much USG couldn’t afford it by cutting entitlements, even if these incentives increased births by 50%, and the average kid will pay far more than $200,000 in taxes in their lifetimes. This seems like a winner, if you can pry political power from the cold, dead hands of the retiree lobby, but is it?

There are two major groups13 that would benefit from this, those being already-stable couples (married or long-term cohabitation) with children deciding whether or not to have the marginal child (going from 2 to 3, or 3 to 4), and the American underclass, in which single-motherhood and relying on government programs to make up the income is already the norm. The extra money will not help people who want to enter a stable relationship before having kids do that, and might even hurt them (since they’ll be paying higher taxes).

This incentive would be far stronger for the underclass, because of their negligible earned income and because they put much less effort into raising their kids than stable married families tend to. Measured in approximate market value, the US underclass (defined by money, education, lack of employment, and lack of marriage), already gets half or more of its income from government programs, which pays for most of this group’s necessities and many of its luxuries.

But cash is much more valuable to this group than in-kind government benefits like food stamps or Section 8, hence the phenomenon of using EBT cards to buy staples, then re-selling those staples for a fraction of the cost and using the money to buy luxuries. Hanson’s proposal is essentially offering a decade or more earned income to this group for having a kid, plus all of the in-kind benefits they already get which pay for actually raising the kids (which will not be taken away) vs maybe two years (and none of the additional benefits for ongoing expenses) for the typical married couple. If the government gave a no-questions asked $200,000 check per kid, you would see a subculture of women having a kid for the check, immediately blowing the money, and then having another kid next year pop up overnight. Having a dozen kids, not really raising them (someone will take care of it, since we don’t let kids with negligent parents die), and living like a millionaire would be a genuine lifestyle for some women throughout their childbearing years.

The silver lining of the worldwide post-2012 fertility decline is where it is concentrated. The strong negative education/income/status-fertility relationship characteristic of the demographic transition is flattening out and possibly even reversing in some countries because lower-class, less-educated women are much less likely to get married or (in countries where formal marriage has little cultural clout, like Sweden) get in long-term stable relationships.

This phenomenon means that while dysgenics is still ongoing both between and within countries, it is not nearly as bad as it used to be. But that could easily be reversed by giving out large unconditional sums of money for children. This is not idle speculation. Underclass women14 having children for the benefits (and unemployed underclass men living off of a mix of their girlfriend’s baby money and petty crime) used to be a common-enough phenomenon to motivate Bill Clinton’s bipartisan welfare reform. Before this reform, the US government paid poor mothers large sums per kid. The average Aid for Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) payment in 1994, after state-level cuts had already begun was $420/month/family ($918/month, $11,016/year in 2025 dollars), enough for non-working poor families to have similar incomes to working ones, especially in heavily-black areas.

These children were generally not well taken care of, requiring (since the United States does not let poorly-raised children go hungry or sick or unattended) further government programs to raise and (behavioral genetics being what it is) typically even more to survive in adulthood, to say nothing of the large criminal fraction. An immediate $200,000 check is enormously more generous than these benefits, especially given this group’s extremely high time-preference.

There’s some evidence that the 1996 welfare reforms had no effect on fertility, but a priori that’s unlikely (and indeed, if giving parents money doesn’t lead to at least slightly higher fertility, political pronatalism is dead in the water). The resolution to this contradiction is that prior state level reforms and media campaigns led to widespread (~61% of black women) expectations that welfare would soon be ended (Clinton ran on ending welfare in 1992) and so fertility in the relevant subgroups began the downwards trend before the 1996 federal law because of these expectations.

I think huge, unconditional cash benefits for children could work in countries with no racial underclass and no culture of single motherhood, like South Korea or Japan, but the likely effect in the United States or most Western countries is a return to the situation prevailing in the 1980s, wherein the stupid and dysfunctional have enormous numbers of net-negative children, which would be bad for both the state’s finances and everyone else, who would both be paying directly for these children at birth, paying more to raise them, and then paying to get away from them once they grew up. It would make France’s current pro-natal state, which encourages the proliferation of unemployed Africans and Arabs, look like a eugenicist’s fantasy. I would expect a similar racial/status fertility gradient as existed in Latin America in the second half of the 20th century to develop.

I worry that many pro-natalists know and understand why an extremely fertile underclass is a bad thing, but that the extremely strong political and moral taboo against racism stops them from addressing this directly, and so we begin to see proposals that, were egalitarianism actually correct, would work… but in the real world, where it isn’t, would be a disaster. I worry even more that some pro-natalists are starting to view maximizing the number of people physically on Earth without regard for who they are as a goal in and of itself, and see an Age of Malthusian Industrialism as something to strive for rather than a dystopia to be avoided. This is a problem when the movement is picking up political steam.

I am amazed at the number of people who cite low Iranian fertility as evidence that feminism, secularism, or education are irrelevant, apparently not knowing about this very successful population control campaign, that the Iranian population is very secular, that Iranian women outnumber men in higher education (more than 60% of the total, rising to 70% in engineering), or that Iran has one of the highest education-to-workforce ratios in the world (behind only South Korea, Poland, Russia, Finland, Israel, and Turkey in 2007).

Which is not the same as saying it doesn’t work at all. But I can’t help but notice that the big successes touted by professional pro-natalist activists are things like “fertility still collapsed, but TFR was 0.1-0.2 higher than the counterfactual.” Even this is likely overstated because of the standard pro-intervention bias you find in most academic social sciences literature and because most papers look at short-run effects. Pro-natal programs tend to “fade out” because they pull births forward without changing cohort fertility as much you’d naively extrapolate expect by looking at TFR or birth rate changes. Contrast this with anti-natalists dropping TFR from 6 to 2 in 20 years in Iran, or Nazi Germany raising it from 1.6 to 2.6 in a decade.

Israeli fertility is often held out as exceptional and credited to a nationalist and pronatalist state, but that’s not really true. The fertility of Israel’s various streams is about what you’d naively expect and comparable to similar groups elsewhere. Israel just has by far the highest fraction of “breeder cults” (ultra-Orthodox Jews), serious patriarchal Abrahamic religious groups (religious Zionists), and religious Middle Easterners (“traditional” sector, most Mizrahi, Arabs). A Netherlands that was 15% Amish, 10% orthodox Calvinists, and 50% Arab would be similar. Secular Israeli Jews are higher than most similar groups (TFR: 1.9), but not exceptionally so. This is about the same as Iceland or South Dakota, and probably increased by cultural spillover from the religious.

Orthodox Judaism is costly and difficult to practice. Even in its non-ultra-Orthodox form it’s far stricter than most Christian or other religious groups, in a way not captured by conventional metrics of religiosity like worship attendance.

You can see shades of this worldview in intellectuals today who argue for immigration on the grounds that immigrants are superior subjects to their native counterparts because of their lower crime rates, higher marriage rates, stronger worker ethic, and (if Asian) higher educational attainment, and that increasing the number of subjects increases the power of the state, allowing us to “beat China.” These arguments are not factually correct. Educational attainment in and of itself is bad, immigrants don’t work harder and aren’t more productive than their American counterparts, and immigrant’s descendants regress to their racial means in the United States in terms of both crime and marriage. But even if they were factually correct, this line of argument would still reflect the mindset of an oriental despot or Russian Tsar rather than a self-governing citizen.

Note: organic =/= popular. The 60s changes were not popular in the West until they happened, but they weren’t imposed by a dictatorial oligarchy unlike in the East.

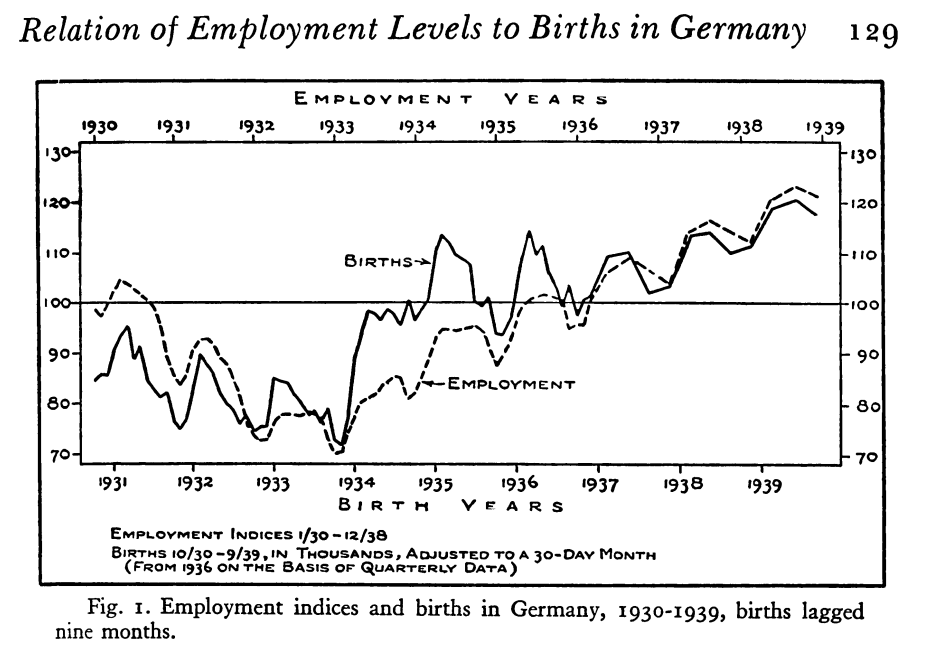

This is also why I don’t think Nazi pro-natalism, which is probably the most successful historical example, is a good example to draw from. The Nazi program combined marriage loans (with 25% forgiven per child), banning abortion (in Weimar Germany the most common method of family planning), increasing male employment through military Keynesianism, and the cultural promotion of motherhood, and German TFR rose from 1.6 to 2.6 from 1933 to 1940. It’s hard to disentangle exactly which of these was most important, but given the similar (though much smaller) rise in Sweden in the same time frame and the rise in fertility as countries exited the Depression in the late 1930s (interrupted by WWII), my belief is that the Nazis effectively started the postwar Baby Boom a decade early by increasing male employment. This would not have worked if the factors that connected male employment to fertility were taken away, as they were with second-wave feminism between 1963 and 1973. Eastern Bloc pronatalism, while less successful, was starting with a less advantageous social situation much more comparable to modern states.

And depending on the course of technology, it may never matter. Either artificial or biological singularity renders fertility concerns, along with everything else, irrelevant. My gut feeling is that one or both of these will probably (>50%) render the question moot, but since I can neither predict nor control this, I’d rather write about the base case where neither happens.

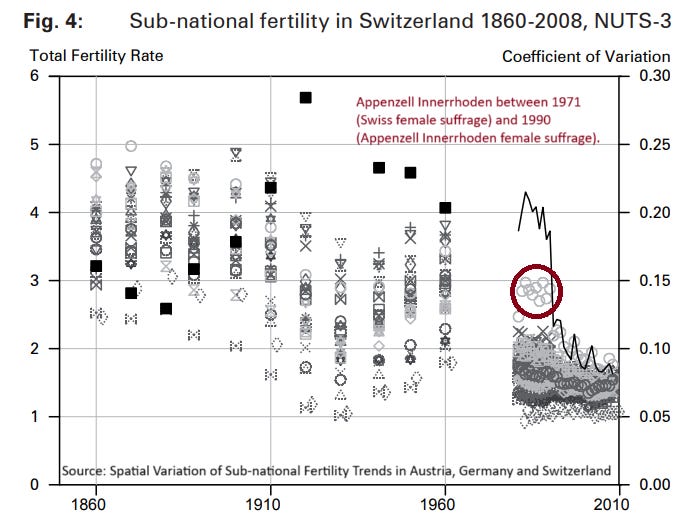

Parenthetically, I’m a little surprised that Switzerland, which did not have a quarter of the relevant cohort of men killed in WWII, was so similar to Germany and Austria.

Though timing matters. If you have two populations with the same life expectancies and completed fertility, but population A has its kids earlier, population A will be both larger and younger at any given point. Both cohort fertility and TFR are useful for different purposes.

This Romanian source claims the tax was later raised, but doesn’t give details or numbers, and the cited subchapter of the book (Politica Pronatalistă A Regimului Ceaușescu II Instituții și practici) does not exist, at least in the Internet Archive version I found. Not sure if the cite is fabricated, a different edition of the book, or something else. Multiple English-language sources claim the tax was 30% on income, but all of them cite this 1987 journal article, which appears to have made the number up. If anyone knows for sure and can send me a primary source, I’d appreciate it.

This is exacerbated by the fact that public sector and quasi-public sector jobs (created by regulation or state pushes for higher female employment, whether via explicit quotas or EEOC lawsuits) tend to be female-dominated (this is not to say all public sector jobs are useless, only that a simple analysis of taxes paid and benefits received will rate make public sector jobs look better than they should).

Plus extremely fertile ethnic subcultures, like Haredi Jews, the Amish, and Somalis. Frankly, I would not be happy about paying $2M to each Somali family in Minneapolis so they can have ten kids each. Haredim and the Amish are less of a problem, but that’s still a lot of money.

Lest I be accused of being too racist: this was not just a black phenomenon, as Charles Murray’s Coming Apart takes pains to document. Lest I be accused of being an anti-racist: in the 90s, this was first and foremost a black phenomenon, with a significant fraction of Latin Americans, especially second-generation and beyond, and a small minority of whites.

Culture also play a large and much less qualifiable role: In the GDR there was a general expectation to have at least one child by the your late twenties at least and people who didn't were generally seen as weird or suspected to be homosexual. This was true across the whole class and educational spectrum too (cf. Angela Merkel, her childlessness and the persistent rumors swirling around her and several women close to her).

This article has contributed more to the topic than almost everything said on twitter over the last decade.